At its core, a rotary vane vacuum pump works by using an off-center spinning rotor with sliding vanes to trap, compress, and exhaust gas molecules from a sealed chamber. As the rotor turns, centrifugal force pushes the vanes against the inner wall of a cylindrical housing, creating chambers of continuously varying volume. This mechanical action effectively sweeps gas from an inlet port to an outlet port, generating a vacuum.

The ingenuity of the rotary vane pump lies in its eccentric design. This simple offset allows a spinning rotor and sliding vanes to continuously create expanding chambers that draw gas in and shrinking chambers that compress and expel it, all in a single fluid motion.

The Core Mechanical Principle

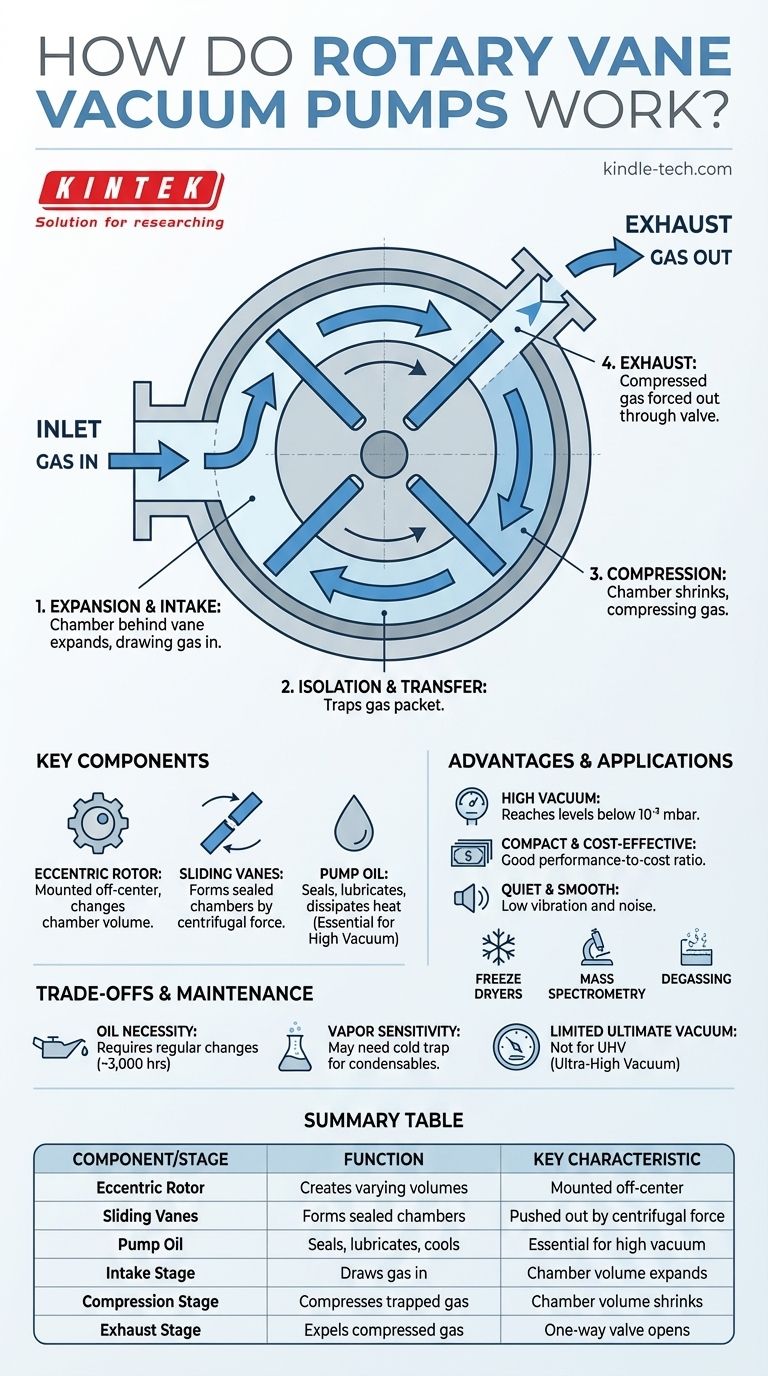

To truly understand the pump's effectiveness, we need to examine its key components and the cycle they perform with each rotation. The entire operation is a continuous, four-step process that repeats thousands of times per minute.

The Eccentric Rotor

The foundation of the pump is a rotor that is mounted eccentrically (off-center) within a larger cylindrical housing, known as the stator. This offset is critical; it ensures that the chambers created by the vanes will change in volume as the rotor spins.

The Sliding Vanes

Slots are cut into the rotor, each containing a flat vane. As the rotor spins, centrifugal force pushes these vanes outward, forcing them to maintain constant contact with the inner wall of the stator. This creates a tight seal and divides the space between the rotor and stator into distinct chambers.

The Four-Step Pumping Cycle

The process of moving gas from the inlet to the exhaust is elegant and efficient.

- Expansion & Intake: As a vane passes the inlet port, the chamber behind it expands. This expansion creates a low-pressure zone, causing gas from the system to be drawn into the pump.

- Isolation & Transfer: As the rotor continues to turn, the trailing vane passes the inlet port. This action traps a specific volume, or "packet," of gas inside the sealed chamber.

- Compression: Due to the rotor's eccentric position, the trapped chamber begins to shrink in volume as it moves toward the outlet port. This mechanically compresses the gas, increasing its pressure.

- Exhaust: The compressed gas eventually reaches a pressure high enough to force open a one-way exhaust valve, expelling it from the pump. The cycle then repeats.

The Critical Role of Oil

Most rotary vane pumps are "wet" or oil-sealed. The oil is not just a lubricant; it serves three essential functions:

- Sealing: It creates an airtight seal between the vanes and the housing, preventing leaks and enabling the pump to reach a high vacuum.

- Lubrication: It minimizes friction and wear on the moving components, ensuring a long operational life.

- Heat Dissipation: It absorbs and transfers heat generated by the compression of the gas, preventing the pump from overheating.

Key Advantages and Applications

The design of the rotary vane pump provides a unique combination of benefits that make it suitable for a wide range of tasks, from laboratory research to industrial processes.

High Vacuum Capability

These pumps are workhorses for creating strong, consistent vacuum pressures, often reaching levels below 10⁻³ mbar. This makes them ideal for applications requiring a near-air-free environment.

Compact and Cost-Effective

Compared to other vacuum technologies that can achieve similar pressures, rotary vane pumps offer an excellent performance-to-cost ratio. Their design is relatively simple, robust, and compact.

Quiet and Smooth Operation

The continuous rotational motion results in very low vibration and noise levels, a significant advantage for laboratory settings or noise-sensitive environments.

Typical Use Cases

You will find rotary vane pumps in demanding applications such as freeze dryers, mass spectrometry, degassing processes, and as primary "roughing" pumps that back more powerful ultra-high vacuum pumps.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Maintenance

While highly effective, this technology comes with specific operational requirements and limitations that are important to understand.

The Necessity of Oil

The oil that is so crucial for performance is also the primary maintenance item. It can become contaminated with vapors from the pumped gases, reducing its effectiveness. Regular oil changes, typically after every 3,000 hours of operation, are necessary to ensure performance and prevent damage.

Sensitivity to Vapors

Because vapors can condense during the compression cycle and contaminate the oil, special care must be taken. For applications with watery or solvent-heavy samples, accessories like a cold trap are often used to freeze the vapors before they can enter the pump.

Limited Ultimate Vacuum

While they produce a "high vacuum," rotary vane pumps cannot reach the "ultra-high vacuum" (UHV) levels required for the most sensitive scientific instruments. In these systems, they serve as an essential first-stage pump.

Making the Right Choice for Your Application

Selecting the correct vacuum technology depends entirely on your goal. A rotary vane pump is often the right choice, but its trade-offs must align with your needs.

- If your primary focus is cost-effective, high vacuum for general lab or industrial use: A rotary vane pump is an excellent and often default choice for its reliability and performance.

- If your primary focus is handling large amounts of condensable vapors: This pump is capable, but you must plan for oil maintenance and likely pair it with a cold trap or gas ballast to protect its integrity.

- If your primary focus is achieving ultra-high vacuum (UHV): A rotary vane pump is best used as the indispensable "roughing" or "backing" pump for a more advanced UHV system, not as the primary UHV pump itself.

Ultimately, the rotary vane pump's exceptional blend of performance, reliability, and value makes it a foundational tool in modern vacuum technology.

Summary Table:

| Component/Stage | Function | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Eccentric Rotor | Creates varying chamber volumes | Mounted off-center within the stator |

| Sliding Vanes | Forms sealed chambers | Pushed out by centrifugal force |

| Pump Oil | Seals, lubricates, and cools | Essential for high vacuum performance |

| Intake Stage | Draws gas into the pump | Chamber volume expands |

| Compression Stage | Compresses trapped gas | Chamber volume shrinks |

| Exhaust Stage | Expels compressed gas | One-way valve opens |

Need a reliable vacuum solution for your laboratory?

KINTEK specializes in high-performance lab equipment, including robust rotary vane vacuum pumps ideal for applications like freeze drying, degassing, and mass spectrometry. Our pumps offer the perfect balance of high vacuum capability, quiet operation, and cost-effectiveness for your research or industrial needs.

Let KINTEK be your partner in precision. Contact our experts today to find the perfect vacuum pump for your specific application and ensure optimal performance and longevity.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Rotary Vane Vacuum Pump for Lab Use

- Circulating Water Vacuum Pump for Laboratory and Industrial Use

- Oil Free Diaphragm Vacuum Pump for Laboratory and Industrial Use

- Electric Heated Hydraulic Vacuum Heat Press for Lab

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Vacuum Box Laboratory Hot Press

People Also Ask

- What is a Rotary Vane Vacuum Pump? Efficiency and Performance for Laboratory Vacuum Systems

- Why is a rotary vane mechanical vacuum pump necessary for sub-surface etching? Ensure Precision in ALD/ALE Experiments

- What are the limitations of rotary vane pumps? Understanding Oil Dependence and Gas Compatibility

- What are the advantages of rotary vane pumps? Unlock Cost-Effective, High-Performance Vacuum

- What is the primary use of a Rotary Vane Vacuum Pump? Expert Guide to Gas Evacuation and Rough Vacuum Ranges