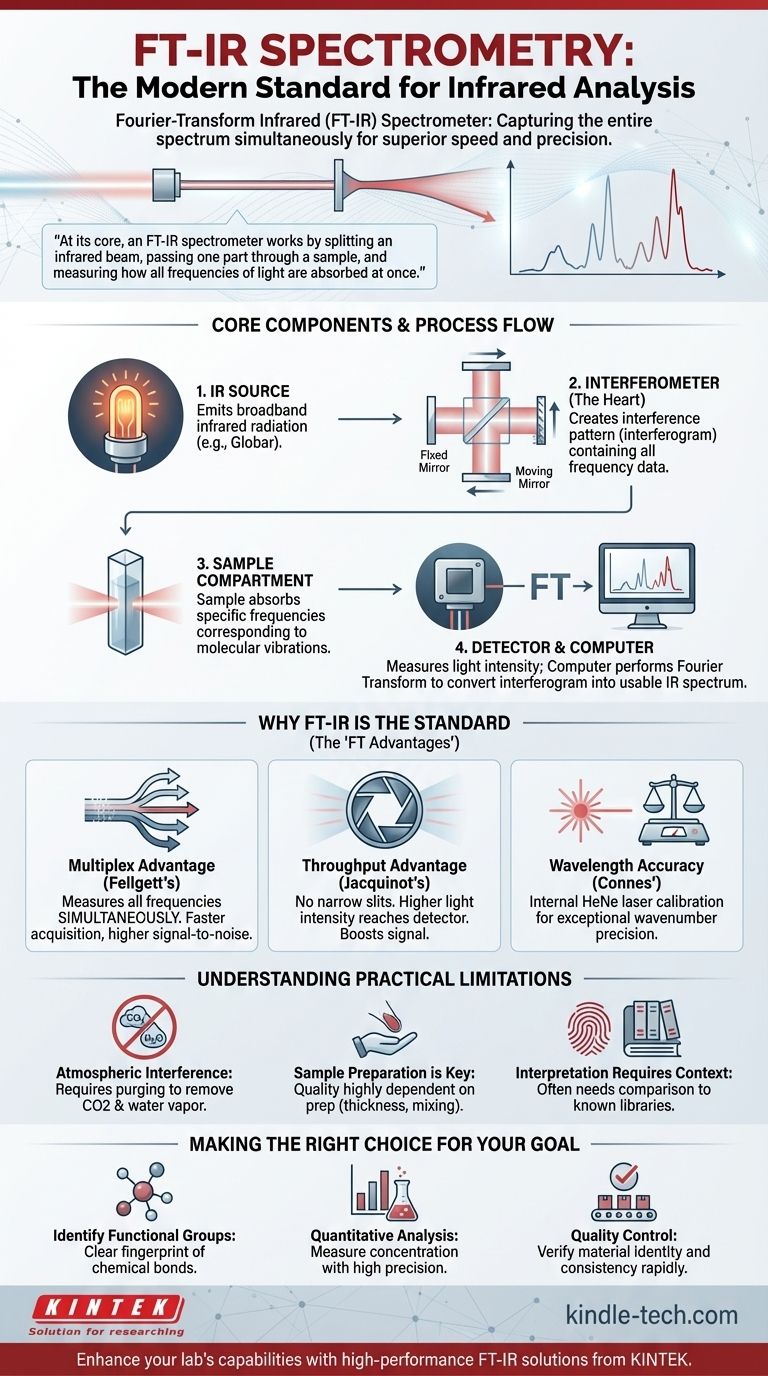

The fundamental instrument used for modern infrared (IR) spectrometry is the Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectrometer. This device has become the industry and laboratory standard because it captures the entire infrared spectrum of a sample simultaneously. It achieves this by measuring an interference pattern of light and then using a mathematical operation, the Fourier Transform, to decode that pattern into a usable spectrum.

At its core, an FT-IR spectrometer works by splitting an infrared beam, passing one part through a sample, and measuring how all frequencies of light are absorbed at once. This parallel data collection is the key to its speed, sensitivity, and precision, making it vastly superior to older, sequential methods.

The Core Components of an FT-IR Spectrometer

To understand how an FT-IR spectrometer works, it is essential to understand its four primary components. Each plays a distinct and critical role in turning a physical sample into a digital spectrum.

The IR Source

The process begins with a source that emits broadband infrared radiation. This is typically a ceramic element, such as a Globar (silicon carbide) or an Ever-Glo (proprietary material), which is heated electrically to glow brightly in the infrared range, providing the light needed for the measurement.

The Interferometer (The Heart of the FT-IR)

This is the most innovative part of the instrument. It consists of a beam splitter, a fixed mirror, and a moving mirror. The beam splitter divides the IR beam into two, sending one to the fixed mirror and the other to the moving mirror.

When the two beams are reflected back, they recombine at the beam splitter. Because the moving mirror has changed the path length of one beam, the waves interfere with each other. This creates a unique, complex signal called an interferogram, which contains all the frequency information at once.

The Sample Compartment

This is a straightforward but critical area where the sample to be analyzed is placed. The recombined infrared beam from the interferometer passes through the sample, which absorbs light at specific frequencies corresponding to the vibrations of its chemical bonds.

The Detector and Computer

A detector, such as a deuterated triglycine sulfate (DTGS) or mercury cadmium telluride (MCT) detector, measures the intensity of the light that makes it through the sample. It records the interferogram, which is a plot of light intensity versus the position of the moving mirror.

This raw signal is not a spectrum. The instrument's computer then performs a Fourier Transform, a fast mathematical algorithm, to convert the interferogram into the familiar IR spectrum: a plot of absorbance versus wavenumber (frequency).

Why FT-IR is the Modern Standard

The FT-IR spectrometer completely replaced older dispersive instruments for several key reasons, often referred to as the "FT advantages."

Fellgett's Advantage (The Multiplex Advantage)

An FT-IR spectrometer measures all frequencies of light simultaneously, rather than scanning through them one by one. This allows it to acquire a complete spectrum in seconds, dramatically improving the signal-to-noise ratio for a given measurement time.

Jacquinot's Advantage (The Throughput Advantage)

Dispersive instruments require narrow slits to select a single wavelength, which blocks most of the light from the source. An FT-IR has no such slits, allowing a much higher intensity of light (throughput) to reach the detector. This further boosts the signal-to-noise ratio.

Connes' Advantage (The Wavelength Accuracy)

FT-IR spectrometers include a helium-neon (HeNe) laser as an internal wavelength calibration standard. The instrument uses the laser's precise, single-frequency signal to know the exact position of the moving mirror at all times, resulting in exceptionally high wavenumber accuracy and precision.

Understanding the Practical Limitations

While powerful, an FT-IR spectrometer is not a magic box. Objective analysis requires acknowledging its limitations.

Sensitivity to Atmospheric Interference

Water vapor and carbon dioxide in the air have strong infrared absorptions. These can overlap with a sample's spectrum, obscuring important peaks. This is why many instruments are purged with dry nitrogen or dry air to remove atmospheric interference.

Sample Preparation is Key

The quality of an IR spectrum is highly dependent on how the sample is prepared. A sample that is too thick will absorb all the light, while poor sample mixing (like in a KBr pellet) will produce a distorted spectrum. The instrument's performance is irrelevant if the sample is prepared improperly.

Interpretation Requires Context

An IR spectrum is a molecular "fingerprint." It excels at identifying the presence of specific functional groups (e.g., C=O, O-H, N-H bonds). However, identifying a complete, unknown molecule often requires comparing the spectrum to a library of known compounds or using complementary analytical techniques.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Understanding the FT-IR's principles allows you to apply it effectively to your specific analytical challenge.

- If your primary focus is identifying functional groups in a compound: The FT-IR is your ideal tool, providing a clear and rapid fingerprint of the chemical bonds present.

- If your primary focus is quantitative analysis: Leverage the FT-IR's high precision and signal-to-noise ratio to measure the concentration of a component in a mixture by applying the Beer-Lambert law.

- If your primary focus is quality control: Use the FT-IR to quickly compare a production sample's spectrum against a trusted reference standard to verify material identity and consistency.

By grasping its core components and principles, the FT-IR spectrometer is transformed from a complex machine into an intuitive and powerful tool for chemical analysis.

Summary Table:

| Component | Function | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| IR Source | Emits broadband infrared light | Heated ceramic element (e.g., Globar) |

| Interferometer | Creates an interference pattern (interferogram) | Beam splitter, fixed and moving mirrors |

| Sample Compartment | Holds the sample for analysis | Light passes through, specific frequencies absorbed |

| Detector & Computer | Measures light intensity and performs Fourier Transform | Converts interferogram into a usable spectrum |

Ready to enhance your laboratory's analytical capabilities?

An FT-IR spectrometer is a cornerstone instrument for identifying functional groups, performing quantitative analysis, and ensuring quality control. At KINTEK, we specialize in providing high-performance lab equipment and consumables tailored to your specific research and industrial needs.

Let us help you achieve precise, reliable results. Our experts will guide you to the ideal FT-IR solution for your application.

Contact our team today to discuss your requirements and discover the KINTEK difference!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- XRF & KBR steel ring lab Powder Pellet Pressing Mold for FTIR

- Three-dimensional electromagnetic sieving instrument

- Lab Electrochemical Workstation Potentiostat for Laboratory Use

- Infrared High Resistance Single Crystal Silicon Lens

- CVD Diamond Optical Windows for Lab Applications

People Also Ask

- Why does casting need heat treatment? Transform Raw Castings into Reliable Components

- What materials are needed for a FTIR? Essential Guide to Sample Prep and Optics

- What requires a medium for heat transfer? Conduction and Convection Explained

- How do vacuum pumps enhance efficiency and performance? Boost Your System's Speed and Lower Costs

- What is the application and principle of centrifugation? Mastering Sample Separation for Your Lab

- Is biochar production sustainable? Unlocking True Carbon Sequestration and Soil Health

- What is the function of temperature control during the drying stage of the biomass gasification process? Optimize Yield

- What is the temperature of sputtering plasma in magnetron? Unlocking the Key to Low-Temperature Thin Film Deposition