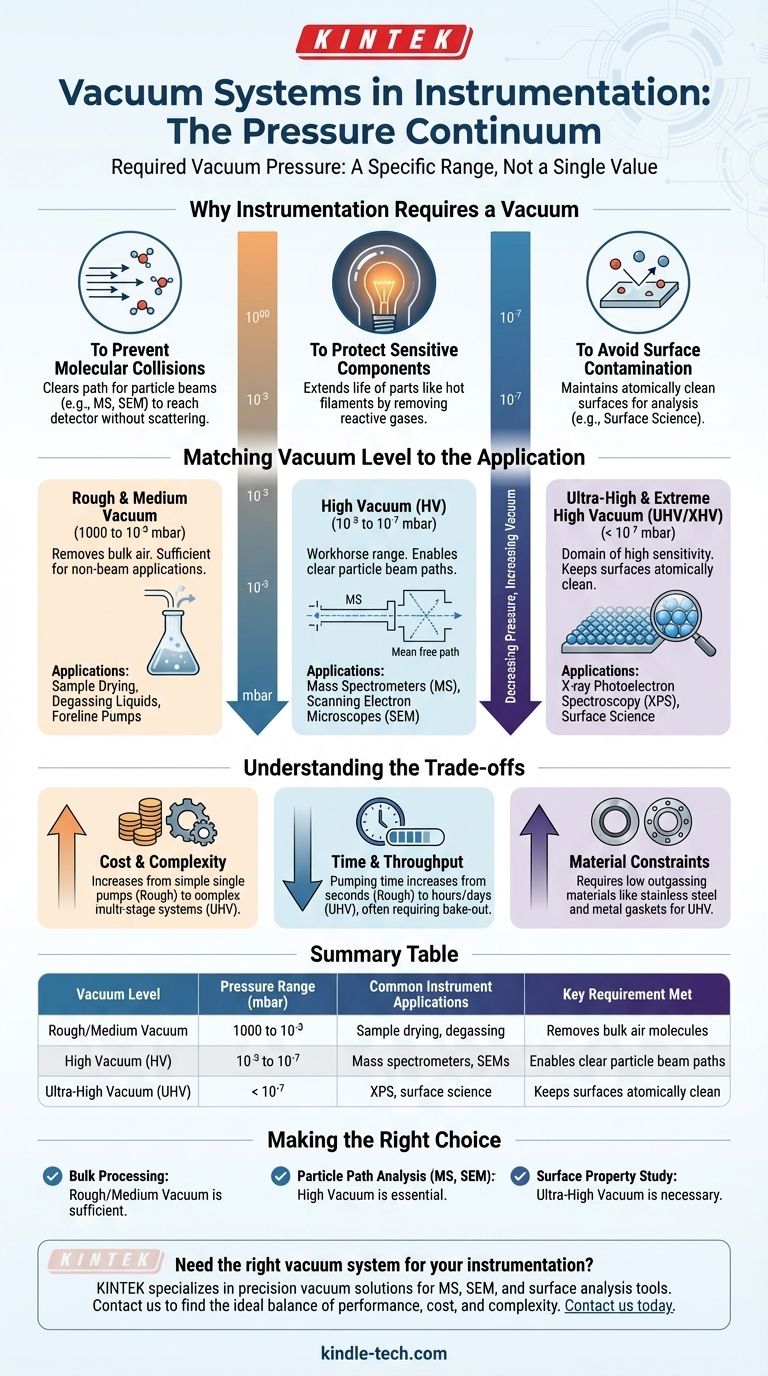

The required vacuum pressure for an instrument is not a single value but rather a specific range dictated entirely by the instrument's function. This can span from a Rough Vacuum (around 1 mbar) for sample preparation to an Ultra-High Vacuum (below 10⁻⁷ mbar) for sensitive surface analysis, with many analytical instruments operating in the High Vacuum range (10⁻³ to 10⁻⁷ mbar).

The core principle is straightforward: the level of vacuum required is determined by the need to eliminate interference from air molecules. The "better" the vacuum (lower the pressure), the fewer molecules remain, and the less likely they are to collide with the particles or samples you are trying to measure.

Why Instrumentation Requires a Vacuum

At its heart, a vacuum system is designed to create a controlled environment by removing atmospheric gas molecules. Different instruments require this control for different reasons, all of which are critical for generating accurate data.

To Prevent Molecular Collisions

Many instruments, like mass spectrometers or electron microscopes, work by accelerating a beam of particles (ions or electrons) from a source to a detector.

In normal air pressure, this beam would immediately collide with billions of nitrogen, oxygen, and other gas molecules. These collisions would scatter the beam, cause unwanted chemical reactions, and make any measurement impossible. A vacuum ensures the particles have a clear, unobstructed path.

To Protect Sensitive Components

Certain components, like the hot filaments used to generate electrons in an electron microscope, would instantly burn out (oxidize) if exposed to oxygen at high temperatures.

A vacuum environment removes the reactive gases, dramatically extending the life and stability of these critical parts.

To Avoid Surface Contamination

For instruments that analyze material surfaces (like surface science techniques), any residual gas molecules in the chamber will quickly stick to and contaminate the sample.

An ultra-high vacuum is necessary to keep a surface atomically clean long enough for an analysis to be completed.

Matching Vacuum Level to the Application

The specific pressure range an instrument needs is directly tied to how much molecular interference it can tolerate. This is why vacuum levels are categorized into distinct regimes.

Rough & Medium Vacuum (1000 to 10⁻³ mbar)

This level of vacuum removes the vast majority of air molecules but still leaves a significant number behind.

It is sufficient for applications like sample drying, degassing liquids, or serving as the initial "foreline" pressure for more powerful high-vacuum pumps. It is not suitable for instruments with particle beams.

High Vacuum (HV) (10⁻³ to 10⁻⁷ mbar)

This is the workhorse range for a vast number of analytical instruments, including most mass spectrometers (MS) and scanning electron microscopes (SEM).

At these pressures, the average distance a molecule can travel before hitting another (the mean free path) becomes longer than the dimensions of the instrument's chamber. This ensures that particles can travel from the source to the detector without collision, enabling accurate measurement.

Ultra-High & Extreme High Vacuum (UHV/XHV) (< 10⁻⁷ mbar)

This is the domain of highly sensitive surface science and semiconductor manufacturing.

At these extremely low pressures, it can take minutes, hours, or even days for a single layer of gas molecules to form on a pristine surface. This gives researchers the time needed to perform detailed analyses on uncontaminated samples using techniques like X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS).

Understanding the Trade-offs

Choosing a vacuum level is not simply about aiming for the lowest possible pressure. Higher levels of vacuum introduce significant practical challenges.

Cost and Complexity

Achieving a rough vacuum requires a single, relatively inexpensive mechanical pump. Achieving UHV requires a multi-stage system with several pumps (e.g., mechanical, turbomolecular, and ion pumps), specialized all-metal components, and complex control systems, making it orders of magnitude more expensive.

Time and Throughput

A rough vacuum can be achieved in seconds or minutes. Pumping a system down to high vacuum might take an hour. Reaching UHV can take many hours or even days, often requiring the entire system to be "baked out" at high temperatures to drive off adsorbed water and gas molecules from the chamber walls.

Material Constraints

Low-vacuum systems can use simple rubber O-rings and flexible materials. UHV systems demand stainless steel construction, metal gaskets (like copper), and materials with very low outgassing rates to avoid being a source of contamination themselves.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The correct vacuum pressure is the one that meets the minimum requirements for your measurement without adding unnecessary cost and complexity.

- If your primary focus is bulk material processing like drying or degassing: A rough or medium vacuum is sufficient and highly cost-effective.

- If your primary focus is analyzing particle paths, like in a standard mass spectrometer or SEM: High vacuum is the non-negotiable standard to ensure a clear path from source to detector.

- If your primary focus is studying the fundamental properties of an atomically clean surface: Ultra-high vacuum is essential to provide a pristine environment free from atmospheric contamination.

Ultimately, selecting the right vacuum level is about creating an environment where your instrument can perform its measurement reliably and without interference.

Summary Table:

| Vacuum Level | Pressure Range (mbar) | Common Instrument Applications | Key Requirement Met |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rough/Medium Vacuum | 1000 to 10⁻³ | Sample drying, degassing | Removes bulk air molecules |

| High Vacuum (HV) | 10⁻³ to 10⁻⁷ | Mass spectrometers, SEMs | Enables clear particle beam paths |

| Ultra-High Vacuum (UHV) | < 10⁻⁷ | XPS, surface science | Keeps surfaces atomically clean |

Need the right vacuum system for your instrumentation? KINTEK specializes in lab equipment and consumables, serving laboratory needs with precision vacuum solutions for mass spectrometers, SEMs, and surface analysis tools. Our experts will help you select the ideal system that balances performance, cost, and complexity for your specific application. Contact us today to ensure your measurements are accurate and interference-free!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Circulating Water Vacuum Pump for Laboratory and Industrial Use

- Laboratory Benchtop Water Circulating Vacuum Pump for Lab Use

- Laboratory Rotary Vane Vacuum Pump for Lab Use

- Oil Free Diaphragm Vacuum Pump for Laboratory and Industrial Use

- Electric Heated Hydraulic Vacuum Heat Press for Lab

People Also Ask

- What is vacuum hardening process? Achieve Superior Hardness with a Pristine Surface Finish

- How does arc melting equipment facilitate the preparation of refractory multi-principal element alloys (RMPEAs)?

- Why is thin-film deposition typically performed in vacuum? Ensure High Purity and Precise Control

- What are the requirements for a heat treatment furnace? A Guide to Precise Temperature and Atmosphere Control

- Why is a high-temperature furnace required for ISR in 5Cr-0.5Mo steel? Prevent Hydrogen Cracking & Residual Stress

- What are the benefits of heat treatment? Enhance Material Strength, Durability, and Performance

- What is the primary use of furnace in the chemical industry? Master Thermal Treatment for Material Transformation

- What is the temperature used in hardening? Master the Key to Steel Hardening Success