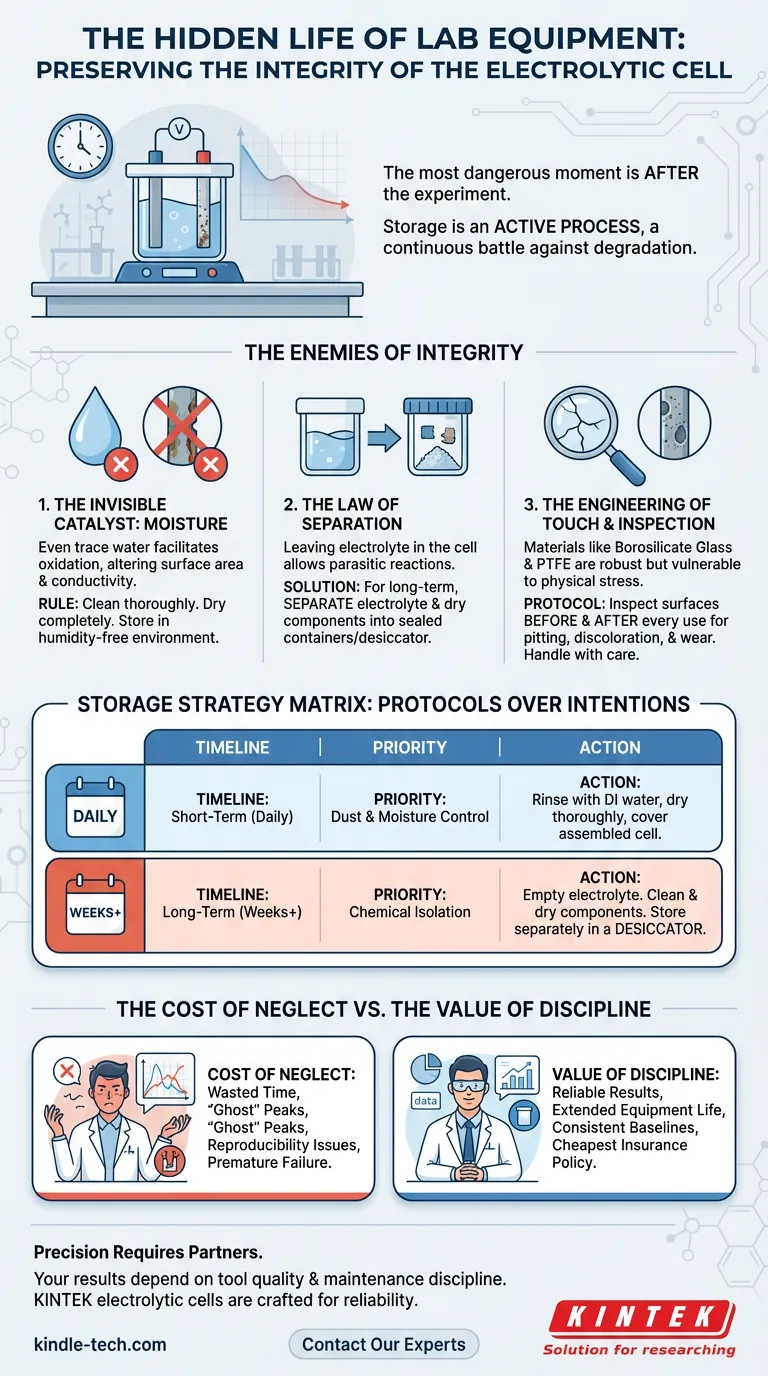

The most dangerous moment for scientific equipment is not during the experiment. It is immediately after.

When the data is collected and the graph is plotted, the human mind moves on. The adrenaline of discovery fades, and the equipment becomes a chore. But for a multifunctional electrolytic cell, this is when the real chemistry begins—the chemistry of degradation.

We tend to view storage as a passive act. We put things away. We close the cabinet. We assume the object is frozen in time.

This is a dangerous fallacy.

In the microscopic world of electrochemistry, storage is an active process. It is a continuous battle against entropy, moisture, and residual reactivity. The difference between a cell that lasts for a decade and one that fails in a month is rarely about the quality of manufacture. It is almost always about the discipline of the shut-down procedure.

The Invisible Catalyst

The primary enemy of the electrolytic cell is not physical impact. It is moisture.

Water is the universal solvent, but in the context of storage, it is the universal catalyst for corrosion. Even trace amounts of water left on an electrode’s surface can facilitate oxidation.

This oxidation alters the surface area and the conductivity of the material. When you return to the lab a week later, you are not using the same electrode. You are using a slightly degraded version of it. The baseline has shifted. The data is compromised before you even turn the potentiostat on.

The rule is absolute:

- Clean components thoroughly.

- Dry them completely.

- Store in a humidity-free environment.

The Law of Separation

There is a temptation, born of efficiency, to leave the electrolyte in the cell. We tell ourselves we will run another scan in the morning.

This is the equivalent of leaving a car engine running in a closed garage.

The interaction between the electrolyte and the electrode does not stop just because you stopped recording data. Slow, parasitic reactions continue. Ions migrate. Surfaces plate. The electrolyte itself can become contaminated by the very vessel holding it.

For long-term storage, the electrolyte must be divorced from the cell. The fluid goes into a sealed container; the dry cell components go into a desiccator. Separation preserves the integrity of both.

The Engineering of Touch

There is a certain romance to the materials used in high-quality electrolytic cells.

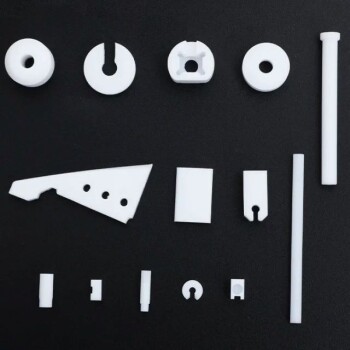

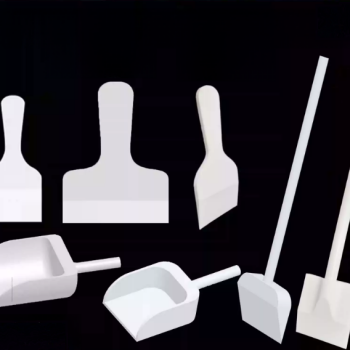

We use High Borosilicate Glass for the body because it offers thermal stability and optical clarity. We use PTFE (Polytetrafluoroethylene) for lids and fittings because of its legendary chemical inertness.

These materials are chosen for their refusal to interact with the world. But they have vulnerabilities.

Glass is rigid and brittle. It demands a deliberate, gentle touch. A chipped joint or a cracked vessel is usually the result of rushing—a moment of physical carelessness during the cleaning process.

Routine Inspection Protocol: Before and after every use, look closely at the electrode surfaces.

- Is there pitting?

- Is there discoloration?

- Is there physical wear?

Early detection of corrosion is the only way to save a noble metal electrode. Once the damage is macroscopic, it is often irreversible.

Protocols Over Intentions

In his study of surgical complications, Atul Gawande noted that errors rarely occur because of a lack of knowledge. They occur because of a lack of consistency.

The same applies to the laboratory. You know you should clean the cell. But without a rigid protocol, "clean" becomes subjective.

For noble metal electrodes (like platinum), a "rinse" is insufficient. A soak in dilute acid (e.g., 1M nitric acid) followed by a deionized water rinse is required to strip away reaction byproducts. For air-sensitive electrodes, storage isn't just a cabinet—it is a nitrogen-filled glovebox.

Your storage strategy must be dictated by your timeline.

Storage Strategy Matrix

| Timeline | The Priority | The Action |

|---|---|---|

| Short-Term (Daily) | Dust & Moisture Control | Rinse with DI water, dry thoroughly, cover the assembled cell. |

| Long-Term (Weeks+) | Chemical Isolation | Empty electrolyte. Clean and dry components. Store separately in a desiccator. |

The Cost of Neglect

The cost of a broken cell is obvious: the price of a replacement.

But the cost of a poorly stored cell is hidden and far higher. It is the cost of wasted time. It is the cost of chasing "ghost" peaks in your voltammetry caused by surface contamination. It is the cost of reproducibility issues that cannot be explained.

A disciplined maintenance routine is the cheapest insurance policy in science.

Precision Requires Partners

Your experimental results are only as good as the tools you use to measure them. While discipline protects your equipment, the quality of that equipment dictates the ceiling of your potential.

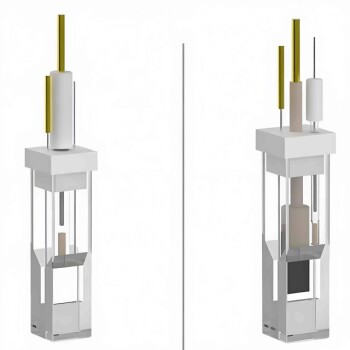

At KINTEK, we understand the engineer's need for reliability. Our electrolytic cells are crafted from high-grade borosilicate glass and durable PTFE, designed to withstand the rigors of serious research—provided they are treated with respect.

Don't let equipment degradation be the variable you didn't account for. Ensure your lab is equipped with tools worthy of your research.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

- PTFE Electrolytic Cell Electrochemical Cell Corrosion-Resistant Sealed and Non-Sealed

- Side Window Optical Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Customizable PEM Electrolysis Cells for Diverse Research Applications

- Thin-Layer Spectral Electrolysis Electrochemical Cell

Related Articles

- The Vessel of Truth: Why the Container Matters More Than the Chemistry

- The Glass Heart: Why Good Science Dies in Dirty Cells

- The Fragile Vessel of Truth: A Maintenance Manifesto for Electrolytic Cells

- The Transparency Paradox: Mastering the Fragile Art of Electrolytic Cells

- Handheld Coating Thickness Gauges: Accurate Measurement for Electroplating and Industrial Coatings