The Psychology of the Shutdown

There is a distinct drop in energy the moment an experiment concludes.

The data is captured. The hypothesis is confirmed or denied. The dopamine hit of discovery is fading. In this moment, the human brain wants to do one thing: disconnect.

We want to flip a switch, walk away, and process the results.

But this is the moment where equipment failure begins. It rarely happens during the stress of operation. It happens during the neglect of the shutdown.

A super-sealed electrolytic cell is a precision instrument. It remembers exactly how you treated it when you were tired.

Proper post-use procedure isn't merely about "tidiness." It is an investment in the accuracy of your next discovery. It is the preservation of a baseline.

Here is the engineer’s protocol for closing the loop.

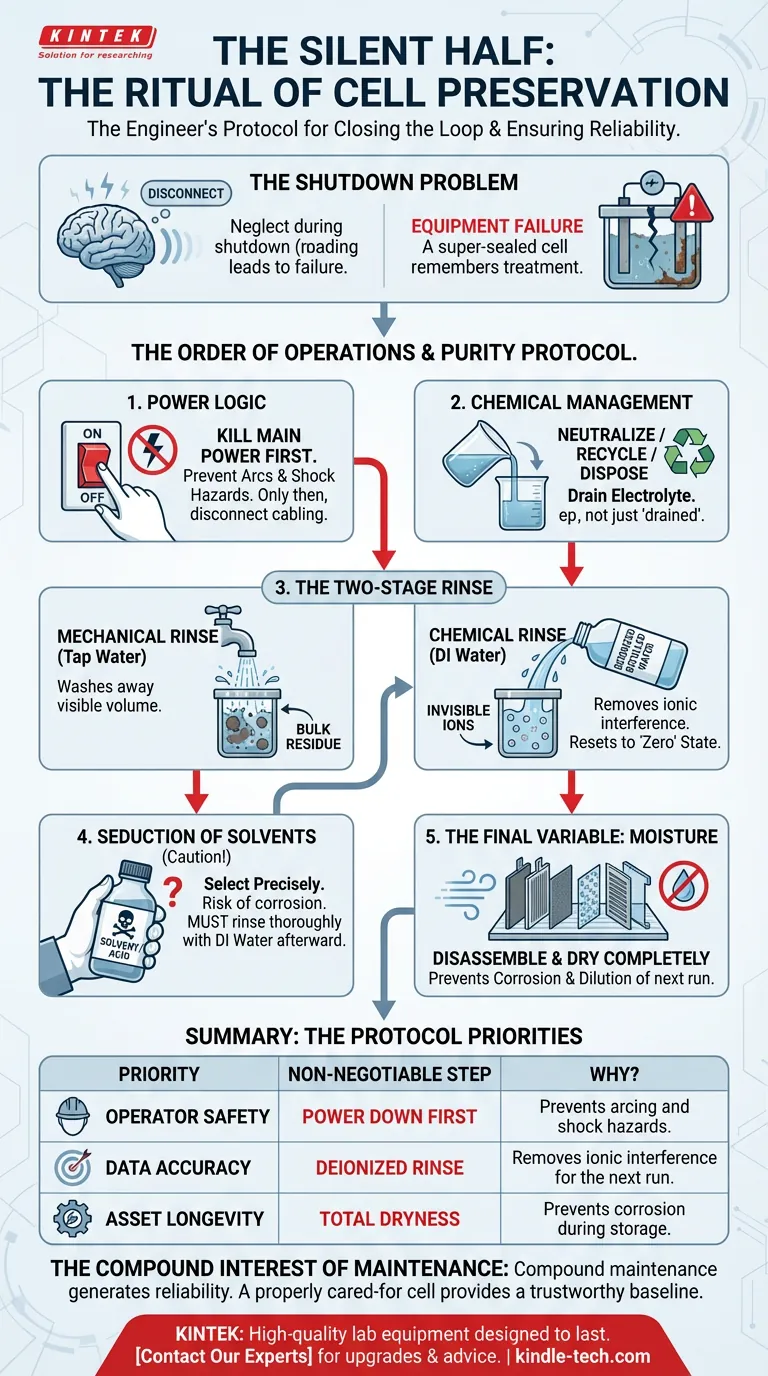

The Order of Operations

Safety is often treated as a checklist. It should be treated as a sequence of dependencies.

When dealing with electrochemical systems, the order of disconnection dictates your safety.

1. Power Logic

Electricity does not care about your schedule.

Always kill the main power supply first.

Only after the flow of current has ceased should you touch the cabling. If you disconnect the cell from the circuitry while the power is live, you risk electrical arcs.

An arc is uncontrolled energy. It damages connectors. It risks operator safety. It ruins the predictability of the instrument.

2. Chemical Management

Once the power is cut, you are left with the chemistry.

Pouring out the electrolyte is not just disposal; it is hazard management.

- Neutralize: If required by the chemical properties.

- Recycle: If the material is valuable.

- Dispose: Strictly following environmental guidelines.

The goal is to leave the vessel empty, not just "drained."

The Hierarchy of Purity

Cleaning is a two-stage process. Most lab errors stem from confusing these two stages.

The Mechanical Rinse

The first rinse uses tap water.

This is a blunt instrument. Its job is mechanical—to wash away the bulk of the residual electrolyte. It removes the visible volume.

The Chemical Rinse

The second rinse must use deionized or distilled water.

Tap water contains ions. If you leave tap water to dry on your electrodes, you are depositing contaminants. You are essentially salting your own equipment.

Multiple rinses with deionized water remove the invisible ions. This resets the cell to a true "zero" state.

The Seduction of Solvents

When distilled water isn't enough, we get frustrated. We reach for stronger stuff.

This is a critical decision point.

If you must use a solvent, dilute acid, or alkali solution to remove stubborn residue, you must be precise.

The Risk: A chemically incompatible cleaner is a slow poison to your equipment. It can corrode the sealing surfaces or pit the electrode materials. Once the structural integrity is compromised, the "super-sealed" nature of the cell is lost.

The Aftermath: Even the correct cleaner is a contaminant if left behind. You must rinse the cleaning agent itself out with distilled water.

If you skip this, your next experiment isn't testing your sample. It's testing your soap.

The Final Variable: Moisture

The procedure ends with drying.

This step is often rushed. But storage conditions define the lifespan of the hardware.

Disassemble the electrodes carefully. They are the heart of the system. Clean them according to their specific material constraints.

Then, let everything dry completely.

Residual moisture in a stored cell does two things:

- It corrodes: Water and oxygen are the parents of rust.

- It dilutes: Any water left in the cell will dilute the electrolyte of your next experiment, skewing concentration data.

Summary: The Protocol

Your priority dictates your focus. However, a sustainable lab balances all three aspects below.

| If your priority is... | The Non-Negotiable Step | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Operator Safety | Power Down First | Prevents arcing and shock hazards. |

| Data Accuracy | Deionized Rinse | Removes ionic interference for the next run. |

| Asset Longevity | Total Dryness | Prevents corrosion during storage. |

The Compound Interest of Maintenance

In finance, compound interest generates wealth. In the laboratory, compound maintenance generates reliability.

A super-sealed electrolytic cell that is properly shut down, cleaned, and dried today will give you a trustworthy baseline tomorrow.

At KINTEK, we build our equipment to withstand the rigors of serious science. But even the best tools require respect. We specialize in high-quality lab equipment and consumables designed to last—provided you handle the "silent half" of the experiment with care.

Do not let a sloppy shutdown compromise a perfect experiment.

Contact Our Experts to discuss upgrading your laboratory setup or to get specific maintenance advice for your electrochemical applications.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory manual slicer

- 1800℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace Bottom Lifting Muffle Furnace

- Non Consumable Vacuum Arc Induction Melting Furnace

Related Articles

- The Art of the Empty Vessel: Preparing Quartz Electrolytic Cells for Absolute Precision

- The Invisible 90%: Why Spectroelectrochemistry Succeeds Before It Begins

- The Art of Resistance: Why Your Electrolytic Cell Needs Breathing Room

- The Invisible Variable: Why Cell Maintenance Defines Electrochemical Truth

- The Invisible Architecture of Precision: Mastery Before the Current Flows