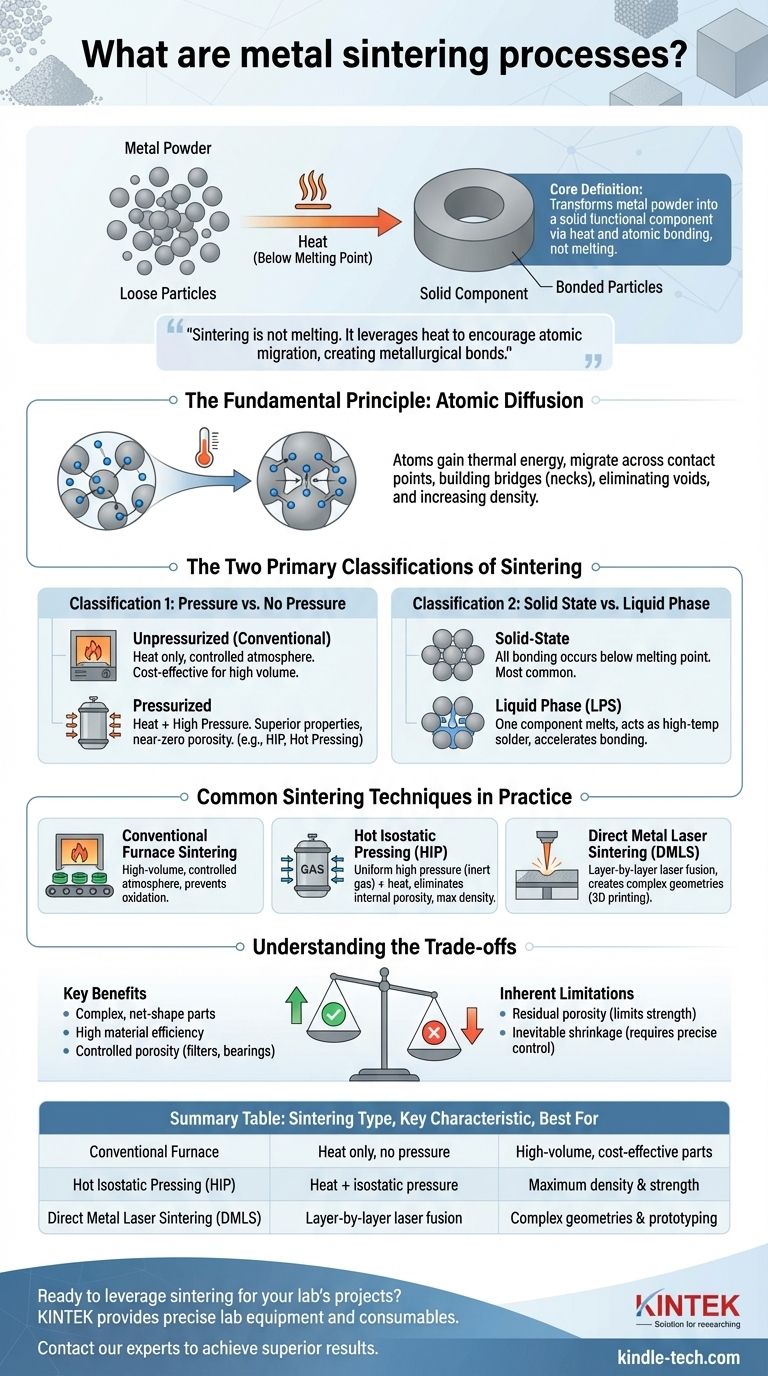

At its core, metal sintering is a manufacturing process that transforms metal powder into a solid, functional component. It achieves this by applying heat below the material's melting point, causing the individual powder particles to bond and fuse together. This process allows for the creation of strong, often complex parts directly from a powdered raw material, eliminating many traditional machining steps.

The crucial concept to grasp is that sintering is not melting. Instead, it leverages heat and sometimes pressure to encourage atoms to migrate between powder particles, creating powerful metallurgical bonds that turn loose powder into a dense, solid object.

The Fundamental Principle: Atomic Diffusion

Sintering works by activating a natural physical process called solid-state diffusion. Understanding this principle is key to understanding the entire technology.

How Heat Unlocks Bonding

When a compacted collection of metal powder—often called a "green part"—is heated, its atoms gain thermal energy. This energy allows atoms at the surface of each particle to become mobile.

They begin to migrate across the contact points between adjacent particles, effectively building bridges between them.

From Powder to a Solid Mass

As this atomic migration continues, the initial contact points grow into larger "necks." This process gradually eliminates the voids or pores between the particles, causing the entire component to shrink and increase in density.

The result is a single, solid piece of metal where billions of individual particles once existed.

The Two Primary Classifications of Sintering

While many specific techniques exist, most can be understood through two fundamental classification systems: the use of pressure and the state of the material during the process.

Classification 1: Pressure vs. No Pressure

The first major distinction is whether external pressure is applied along with heat.

- Unpressurized Sintering (Conventional): In this method, a powder compact is simply heated in a controlled-atmosphere furnace. The bonding is driven entirely by thermal energy. This is the most common and cost-effective method for large-scale production.

- Pressurized Sintering: This approach applies high pressure and temperature simultaneously. The external pressure physically forces the particles closer together, accelerating densification and resulting in parts with superior mechanical properties and near-zero porosity. Examples include Hot Pressing and Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP).

Classification 2: Solid State vs. Liquid Phase

The second distinction relates to the physical state of the metal powder during the heating cycle.

- Solid-State Sintering: This is the most common form, where the processing temperature remains below the melting point of all constituent metals in the powder mix. All atomic bonding occurs while the material is entirely solid.

- Liquid Phase Sintering (LPS): This technique is used for metal blends where one component has a lower melting point. During heating, this component melts and becomes a liquid phase that flows into the gaps between the solid particles, acting like a high-temperature solder to rapidly accelerate bonding and densification.

Common Sintering Techniques in Practice

These fundamental principles are applied through several industry-standard techniques, each suited to different applications.

Conventional Furnace Sintering

This is the workhorse of the powder metallurgy industry. Pre-compacted "green parts" are fed through a long furnace with a carefully controlled atmosphere to prevent oxidation, making it ideal for high-volume manufacturing.

Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP)

HIP places parts in a high-pressure vessel filled with an inert gas (like argon) which is then heated. The gas applies uniform pressure from all directions, making it exceptionally effective at eliminating internal porosity and creating parts with performance comparable to wrought metals.

Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS)

A key technology in metal 3D printing, DMLS uses a high-powered laser to fuse thin layers of metal powder, one on top of the other. It is a localized, layer-by-layer sintering process that enables the creation of incredibly complex geometries that are impossible with other methods.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Sintering provides powerful capabilities, but like any engineering process, it involves clear trade-offs that are critical to understand.

The Key Benefits

The primary advantage of sintering is its ability to produce complex, net-shape or near-net-shape parts with high material efficiency, drastically reducing or eliminating the need for wasteful machining.

It also enables the creation of unique material blends and allows for controlled porosity, which is essential for self-lubricating bearings and filters.

Inherent Limitations

The most significant challenge in sintering is managing residual porosity. Unless advanced pressurized methods are used, sintered parts will almost always have some level of microscopic voids, which can limit their ultimate strength and fatigue resistance compared to fully dense forged or machined components.

Furthermore, shrinkage during the process is inevitable and must be precisely predicted and controlled to achieve tight dimensional tolerances.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Selecting the correct sintering approach depends entirely on the component's performance requirements and economic constraints.

- If your primary focus is cost-effective, high-volume production: Conventional unpressurized sintering offers an unbeatable balance of performance and price for millions of identical parts.

- If your primary focus is maximum density and mechanical strength: Pressurized methods like Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) are necessary to achieve properties that rival traditional manufacturing.

- If your primary focus is geometric complexity or rapid prototyping: Additive manufacturing techniques like Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) provide unparalleled design freedom.

By understanding these fundamental processes, you can select the most effective manufacturing path to meet your specific material and performance goals.

Summary Table:

| Sintering Type | Key Characteristic | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Conventional Furnace | Heat only, no pressure | High-volume, cost-effective parts |

| Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) | Heat + isostatic pressure | Maximum density & strength |

| Direct Metal Laser Sintering (DMLS) | Layer-by-layer laser fusion | Complex geometries & prototyping |

Ready to leverage sintering for your lab's projects? KINTEK specializes in providing the precise lab equipment and consumables needed for advanced sintering processes. Whether you are developing new materials or optimizing production, our expertise and high-quality products ensure you achieve superior results. Contact our experts today to discuss how we can support your laboratory's specific needs in powder metallurgy and beyond.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Furnace for Heat Treat and Sintering

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Dental Porcelain Zirconia Sintering Ceramic Furnace Chairside with Transformer

People Also Ask

- Why is a molecular pump vacuum system necessary for titanium matrix composites? Achieve $1 \times 10^{-3}$ Pa High Purity

- What is the significance of applying mechanical pressure via a vacuum hot press? Maximize A356-SiCp Composite Density

- Why is the vacuum system of a Vacuum Hot Pressing furnace critical for ODS ferritic stainless steel performance?

- How does the mechanical pressure from a vacuum hot-pressing furnace facilitate the densification of B4C/Al composites?

- How does the degassing stage in a vacuum hot press (VHP) optimize diamond/aluminum composite performance?