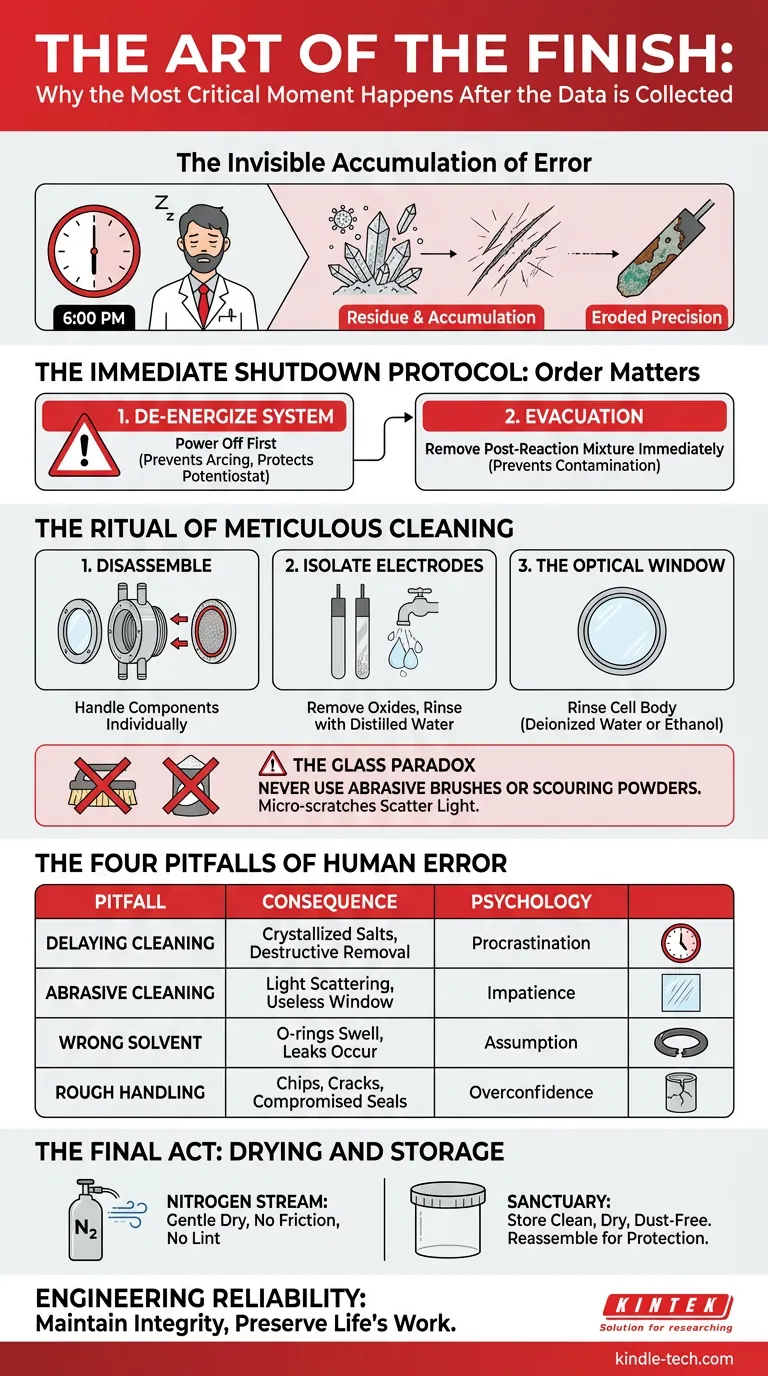

The Invisible Accumulation of Error

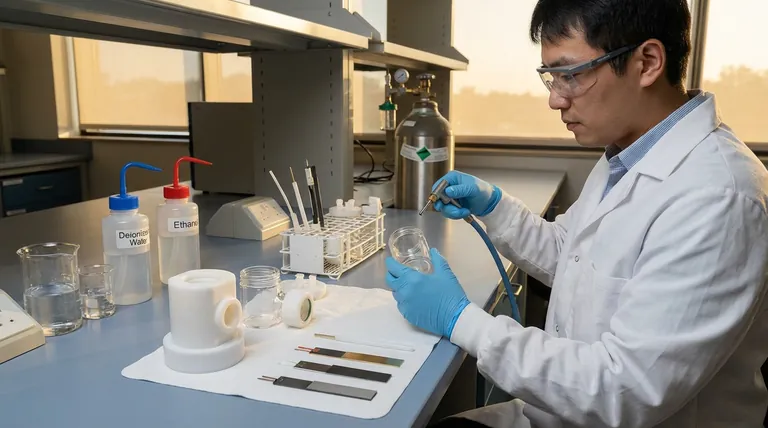

There is a moment in every laboratory, usually around 6:00 PM, that determines the future success of a scientist more than their hypothesis does.

The data is collected. The graphs look promising. The fatigue sets in. The temptation is biological and overwhelming: leave the cleanup for tomorrow morning.

This is the most dangerous moment in the lifecycle of a side-window optical electrolytic cell.

We often view equipment maintenance as a chore—a tax we pay for doing science. But in reality, the shutdown protocol is not separate from the experiment. It is the experiment. It is the variable that defines whether your next reading is a breakthrough or a ghost artifact caused by a microscopic salt crystal left behind three days ago.

Residue compounds. Scratches accumulate. Precision erodes slowly, then all at once.

Here is how to master the art of the shutdown, preserving both your equipment and your data integrity.

The Immediate Shutdown Protocol: Order Matters

Safety is not just about avoiding injury; it is about control. When an electrochemical system is active, it is a live environment. The order in which you dismantle that environment dictates safety.

The Arc and The Spark

The first step is binary. De-energize the system.

You must turn off the power source before touching any electrical leads. This seems obvious, yet it is frequently violated in moments of haste. Disconnecting a live lead can create an electric arc.

An arc does two things:

- It endangers the operator.

- It damages the potentiostat and electrode connections.

Only once the silence of the machine is absolute should you proceed.

Evacuation

Once the energy is gone, the chemistry must follow. Remove the post-reaction mixture immediately.

If the product is valuable, transfer it to storage. If it is waste, dispose of it according to environmental regulations. The goal is an empty vessel. The longer liquid sits, the more likely it is to interact with the cell walls or seals.

The Ritual of Meticulous Cleaning

Cleaning is an exercise in deconstruction. You cannot clean a complex system while it is assembled.

Step 1: Disassemble. Take the cell apart. Remove the working, counter, and reference electrodes. Handling each component individually is the only way to ensure they are truly clean.

Step 2: Isolate the Electrodes. Electrodes have memories. If you don't scrub that memory away, it contaminates the future. Clean them based on their specific material requirements. Remove oxides and dirt. Rinse with distilled water.

Step 3: The Optical Window. This is the heart of the "optical" electrolytic cell. It is a lens into the truth of your reaction.

Rinse the cell body repeatedly with deionized water. If the residue is stubborn, use an organic solvent like ethanol. But here, you must exercise what engineers call "material empathy."

The Glass Paradox

The optical window is strong enough to hold chemical reactions but fragile enough to be ruined by a paper towel.

Never use abrasive brushes. Never use scouring powders.

A single micro-scratch on the window scatters light. Once light scatters, your optical measurements become noise. The window must remain invisible to be useful.

The Four Pitfalls of Human Error

In our experience at KINTEK, equipment failure is rarely caused by the equipment itself. It is caused by a deviation from protocol.

| The Pitfall | The Consequence | The Psychology |

|---|---|---|

| Delaying Cleaning | Salts crystallize and harden. Removal becomes destructive. | "I'll do it tomorrow." (Procrastination) |

| Abrasive Cleaning | Light scattering renders the window useless. | "I need to get this stain off fast." (Impatience) |

| Wrong Solvent | O-rings swell; PTFE degrades; leaks occur. | "This solvent should work." (Assumption) |

| Rough Handling | Chips or cracks in the glass body; compromised seals. | "It feels sturdy enough." (Overconfidence) |

The Final Act: Drying and Storage

You have cleaned the past away. Now you must protect the future.

The Nitrogen Stream Do not rub the components dry. Use a gentle stream of dry nitrogen gas. It is the gold standard for removing moisture without introducing lint or friction.

If nitrogen is unavailable, air drying in a dust-free environment is acceptable. The enemy here is moisture. A single drop of water left in a crevice is a breeding ground for corrosion or a contaminant for tomorrow's anhydrous reaction.

Sanctuary Store the components in a clean, dry, dust-free location. Reassembling the cell for storage is often the best way to protect the delicate optical window from accidental impact or ambient dust.

Engineering Reliability

Your protocol reflects your priorities.

- For Safety: Power off first. Always.

- For Reproducibility: Clean immediately.

- For Longevity: Store properly.

At KINTEK, we believe that the tools of science should be as resilient as the scientists using them. We specialize in high-quality lab equipment and consumables designed to withstand the rigors of serious research—provided they are treated with the respect they deserve.

When you care for your equipment, you are not just maintaining a machine; you are maintaining the integrity of your life's work.

Ready to upgrade your laboratory's capabilities? Contact Our Experts to discuss how KINTEK can support your research with precision equipment and compatible consumables.

Visual Guide

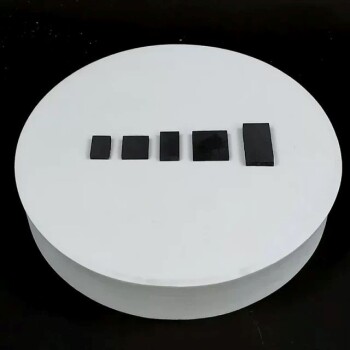

Related Products

- Side Window Optical Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

- Multifunctional Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell Water Bath Single Layer Double Layer

- Glassy Carbon Sheet RVC for Electrochemical Experiments

Related Articles

- Understanding Electrolytic Cells and Their Role in Copper Purification and Electroplating

- Advanced Electrolytic Cell Techniques for Cutting-Edge Lab Research

- Understanding Quartz Electrolytic Cells: Applications, Mechanisms, and Advantages

- The Fragile Intersection: Mastering the Side-Window Optical Electrolytic Cell

- Applications of H-Type Electrolytic Cell in Metal Extraction