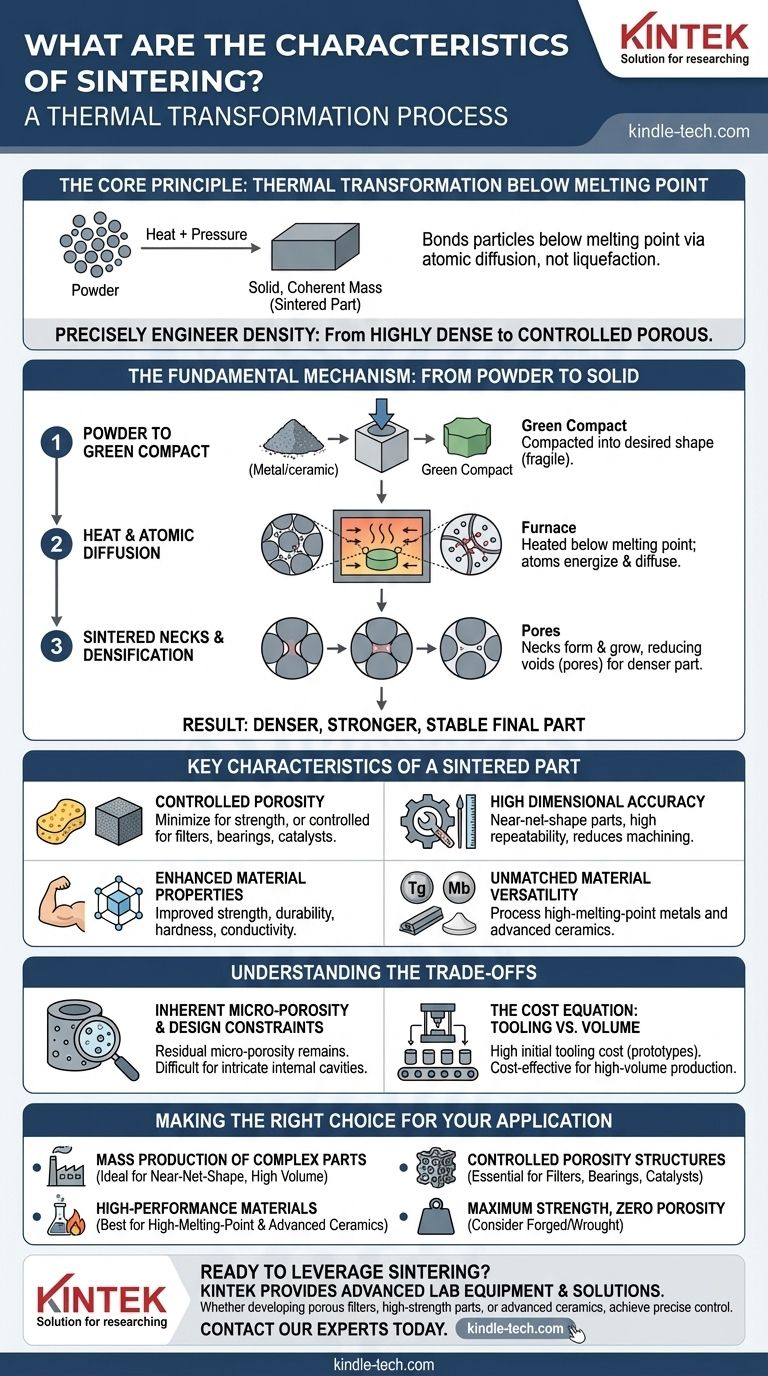

At its core, sintering is a process of thermal transformation. It is a manufacturing method that uses heat and pressure to bond particles of a material together into a solid, coherent mass. Crucially, this is achieved at a temperature below the material's melting point, relying on atomic diffusion rather than liquefaction to create strong, dimensionally accurate components from powders.

While often seen simply as a way to harden powders, the true characteristic of sintering is its ability to precisely engineer a material's final density. This control allows for the creation of everything from highly dense, strong parts to intentionally porous structures for specialized applications.

The Fundamental Mechanism: From Powder to Solid

Sintering is not a simple melting process. It is a sophisticated, solid-state phenomenon that fundamentally changes the material's internal structure.

From Powder to a "Green Compact"

The process begins with a powder, which can be a metal, ceramic, or composite. This powder is first compacted into a desired shape, often using a die and press. This initial, fragile part is known as a "green compact."

The Role of Heat and Atomic Diffusion

The green compact is then heated in a controlled-atmosphere furnace to a temperature below its melting point. This thermal energy doesn't melt the material but instead energizes its atoms.

These energized atoms begin to migrate across the boundaries of the individual particles, a process called atomic diffusion. This movement fuses the particles together where they touch.

Sintered Necks and Densification

As atoms diffuse, they form small bridges or "necks" between adjacent particles. As the process continues, these necks grow wider, pulling the particle centers closer together.

This action systematically reduces the size and number of voids, or pores, that existed between the particles in the green compact. The result is a denser, stronger, and more stable final part.

Key Characteristics of a Sintered Part

The sintering process imparts a unique set of properties to the final component, making it distinct from parts made by casting or machining.

Controlled Porosity

A defining characteristic of sintered parts is their porosity. For many structural applications, the goal is to minimize porosity to achieve maximum density and strength.

However, this porosity can also be a deliberate and controlled feature. Applications like self-lubricating bearings, filters, and catalysts rely on a specific, uniform porous structure that only sintering can reliably produce.

High Dimensional Accuracy

Sintering produces near-net-shape parts, meaning they come out of the furnace very close to their final dimensions. This high degree of repeatability and accuracy significantly reduces or eliminates the need for expensive secondary machining operations.

Enhanced Material Properties

The formation of a bonded, crystalline structure dramatically improves the part's mechanical properties. Sintering increases strength, durability, and hardness compared to the un-sintered powder compact.

The process can also enhance thermal and electrical conductivity by creating a continuous path through the fused particles.

Unmatched Material Versatility

Sintering is exceptionally useful for materials that are difficult or impossible to process by other means. This includes materials with extremely high melting points, such as tungsten and molybdenum, as well as advanced ceramics and hardmetals used for cutting tools.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While powerful, sintering is not the ideal solution for every problem. Understanding its limitations is critical for proper application.

Inherent Micro-Porosity

Even when the goal is full density, most sintered parts retain some level of residual micro-porosity. This can make them less suitable than a fully dense wrought or forged equivalent for applications requiring the absolute highest tensile strength or fatigue resistance.

The Cost Equation: Tooling vs. Volume

The dies and tooling required for compacting the initial powder are expensive. This high initial investment makes sintering cost-prohibitive for prototypes or very small production runs.

Conversely, for high-volume production, the low material waste, high speed, and minimal secondary processing make sintering an extremely cost-effective method.

Design and Material Constraints

Although sintering allows for complex geometries, highly intricate internal cavities or undercuts can still be difficult to produce. The flow and compaction of the initial powder dictate the feasibility of a given design.

Making the Right Choice for Your Application

Selecting a manufacturing process depends entirely on your primary goal. Use these points as a guide.

- If your primary focus is mass production of complex parts: Sintering is ideal for creating repeatable, near-net-shape components at high volume, minimizing costly machining.

- If your primary focus is working with high-performance materials: It is one of the few viable methods for fabricating parts from materials with extremely high melting points or advanced ceramics.

- If your primary focus is creating a structure with controlled porosity: Sintering provides unique and reliable control over final density, essential for filters, bearings, and catalysts.

- If your primary focus is absolute maximum strength with zero porosity: A forged or fully wrought material may be a better choice, as sintering inherently leaves some residual micro-porosity.

By understanding these core characteristics, you can effectively leverage sintering to solve a unique range of complex manufacturing challenges.

Summary Table:

| Characteristic | Description | Key Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Porosity | Ability to create parts with specific, uniform pore structures. | Enables filters, self-lubricating bearings, and catalysts. |

| High Dimensional Accuracy | Produces near-net-shape parts with repeatable precision. | Reduces or eliminates costly secondary machining. |

| Enhanced Material Properties | Improves strength, hardness, and conductivity via atomic diffusion. | Creates durable, high-performance components. |

| Material Versatility | Processes high-melting-point metals (tungsten, molybdenum) and ceramics. | Solves manufacturing challenges for advanced materials. |

| Trade-off: Micro-Porosity | Residual pores remain even in dense parts. | May limit use in applications requiring absolute maximum strength. |

Ready to leverage sintering for your high-performance components? KINTEK specializes in providing the advanced lab equipment and consumables needed to perfect your sintering process. Whether you're developing porous filters, high-strength metal parts, or advanced ceramic components, our expertise ensures you achieve precise control over density and material properties. Contact our experts today to discuss how we can support your laboratory's unique sintering challenges and help you innovate faster.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Dental Porcelain Zirconia Sintering Ceramic Furnace Chairside with Transformer

- Vacuum Dental Porcelain Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace with 9MPa Air Pressure

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Furnace for Heat Treat and Sintering

People Also Ask

- What is a dental oven? The Precision Furnace for Creating Strong, Aesthetic Dental Restorations

- What is the price of zirconia sintering furnace? Invest in Precision, Not Just a Price Tag

- What is the sintering time for zirconia? A Guide to Precise Firing for Optimal Results

- What is one of the newest applications for dental ceramics? Monolithic Zirconia for Full-Arch Bridges

- What is the effect of zirconia sintering temperature? Master the Key to Strength and Stability