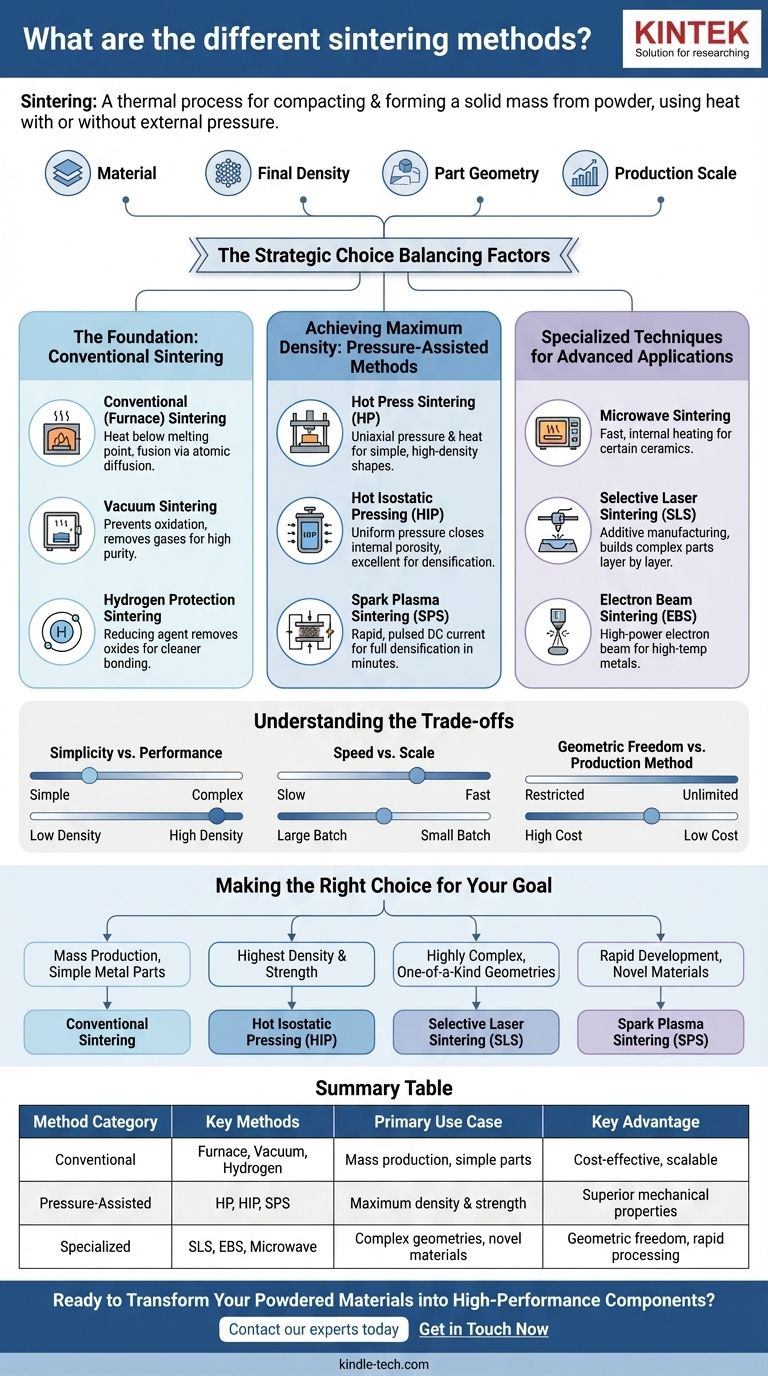

At its core, sintering is a thermal process for compacting and forming a solid mass of material from powder. The various methods are distinguished primarily by how they apply heat and whether they use external pressure, leading to a range of techniques from conventional furnace heating to advanced, energy-beam-based additive manufacturing.

The choice of a sintering method is a strategic decision balancing four critical factors: the material being used, the required final density, the complexity of the part's geometry, and the desired scale of production. There is no single "best" method, only the most appropriate one for your specific goal.

The Foundation: Conventional Sintering

This category represents the most traditional and widely used approaches, relying primarily on thermal energy in a controlled atmosphere without the use of external pressure.

Conventional (Furnace) Sintering

This is the baseline method where a compacted powder component, or "green part," is heated in a furnace below its melting point. The heat allows atoms to diffuse across the boundaries of the particles, fusing them together into a solid piece.

Vacuum Sintering

This is a variation of conventional sintering performed under a vacuum. The primary purpose is to prevent oxidation and remove trapped gases, which is critical for reactive metals or for achieving very high purity in the final part.

Hydrogen Protection Sintering

In this method, the furnace atmosphere is rich in hydrogen. Hydrogen acts as a "reducing agent," actively removing oxides from the surface of the metal powders (like in cemented carbides), promoting a cleaner and stronger bond between particles.

Achieving Maximum Density: Pressure-Assisted Methods

These techniques apply external pressure simultaneously with heat. The pressure dramatically accelerates the densification process, helping to eliminate internal voids (porosity) and achieve superior mechanical properties.

Hot Press Sintering (HP)

Hot pressing involves applying uniaxial (one-direction) pressure to the powder in a die while it is being heated. This is effective for producing simple shapes with very high density, though the process is slower and less scalable than others.

Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP)

In HIP, the part is heated in a high-pressure vessel. An inert gas applies uniform, isostatic (equal in all directions) pressure to the component. This is exceptionally effective at closing any remaining internal porosity and is often used as a secondary step to densify parts made by other methods.

Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS)

SPS is a rapid, pressure-assisted technique where a pulsed DC electrical current is passed directly through the powder and the graphite tooling. This creates instantaneous, localized heating at the particle contact points, enabling full densification in minutes rather than hours. It is a powerful tool for laboratory research and processing novel biomaterials.

Specialized Techniques for Advanced Applications

These methods leverage unique energy sources or layer-by-layer construction to achieve results that are impossible with conventional or pressure-assisted techniques.

Microwave Sintering

This method uses microwave radiation to heat the material. The heating is internal and volumetric, which can be much faster and more energy-efficient than conventional furnace heating. It is particularly effective for certain ceramic materials.

Selective Laser Sintering (SLS)

SLS is an additive manufacturing (3D printing) technique. It uses a high-power laser to scan a bed of powder, selectively fusing material together layer by layer to build a complex, three-dimensional object.

Electron Beam Sintering (EBS)

Similar to SLS, EBS is another additive manufacturing method that uses a focused beam of electrons in a vacuum to fuse powdered materials. It offers different energy absorption characteristics and is often used for high-temperature metals.

Understanding the Trade-offs

No sintering method is without its limitations. The primary trade-off is often between part complexity, production speed, and final material properties.

Simplicity vs. Performance

Conventional methods are relatively simple, scalable, and cost-effective for mass production. However, they may not achieve the full theoretical density of the material, leaving some residual porosity that can impact strength. Pressure-assisted methods yield superior performance but at the cost of more complex and expensive equipment.

Speed vs. Scale

Advanced methods like Spark Plasma Sintering are incredibly fast, but are typically limited to producing smaller, simpler shapes, making them ideal for R&D but not for large-scale manufacturing. Conventional sintering is slow but can process large batches of parts at once.

Geometric Freedom vs. Production Method

The greatest advantage of additive methods like SLS and EBS is near-total geometric freedom. However, this comes at a high cost per part and can be a slow process for mass production compared to shaping a powder in a die and sintering it conventionally.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Selecting the correct method requires a clear understanding of your project's primary objective.

- If your primary focus is mass production of simple metal parts: Conventional sintering in a controlled atmosphere is the most economical and proven path.

- If your primary focus is achieving the highest possible density and mechanical strength: Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) is the definitive choice, either as a primary method or as a post-processing step.

- If your primary focus is creating highly complex, one-of-a-kind geometries: Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) or other additive manufacturing techniques are the only viable options.

- If your primary focus is rapid development of novel or difficult-to-sinter materials: Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) provides an unmatched combination of speed and processing control.

By understanding these fundamental differences, you can select the precise method to transform powdered material into a high-performance final product.

Summary Table:

| Method Category | Key Methods | Primary Use Case | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Furnace, Vacuum, Hydrogen | Mass production of simple parts | Cost-effective, scalable |

| Pressure-Assisted | Hot Pressing (HP), Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP), Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) | Achieving maximum density & strength | Superior mechanical properties |

| Specialized | Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), Electron Beam Sintering (EBS), Microwave | Complex geometries, novel materials | Geometric freedom, rapid processing |

Ready to Transform Your Powdered Materials into High-Performance Components?

Choosing the right sintering method is critical to achieving your desired part density, geometry, and production scale. KINTEK specializes in providing the advanced lab equipment and expert support you need to succeed.

Whether you are developing novel biomaterials with Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS), producing high-strength parts with Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP), or exploring the design freedom of Selective Laser Sintering (SLS), we have the solutions for your laboratory.

Contact our experts today to discuss your specific application and find the perfect sintering solution for your R&D or production needs.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Spark Plasma Sintering Furnace SPS Furnace

- CF KF Flange Vacuum Electrode Feedthrough Lead Sealing Assembly for Vacuum Systems

- Single Punch Electric Tablet Press Machine Laboratory Powder Tablet Punching TDP Tablet Press

- Cylindrical Resonator MPCVD Machine System Reactor for Microwave Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition and Lab Diamond Growth

- Automatic Laboratory Heat Press Machine

People Also Ask

- What are the steps in spark plasma sintering? Achieve Rapid, Low-Temperature Densification

- What is the difference between hot press and SPS? Choose the Right Sintering Method for Your Lab

- What are the advantages of SPS? Achieve Superior Material Density and Performance

- Can aluminum be sintered? Overcome the Oxide Barrier for Complex, Lightweight Parts

- What is the SPS process of spark plasma sintering? A Guide to Rapid, Low-Temperature Densification