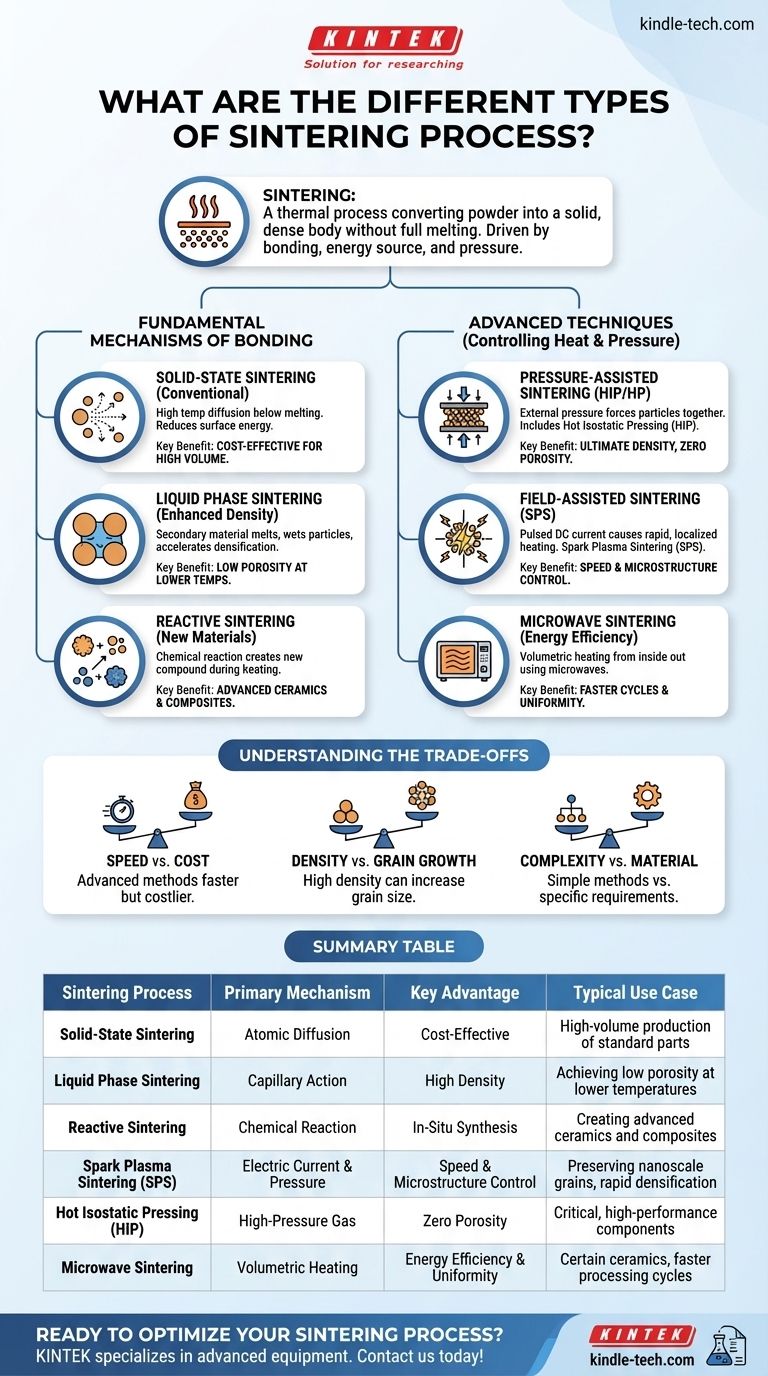

At its core, sintering is a thermal process for converting a powder into a solid, dense body without melting it entirely. The primary types of sintering are differentiated by the mechanism of bonding, the energy source used, and the application of external pressure. These methods include Solid-State Sintering, Liquid Phase Sintering, Reactive Sintering, and advanced techniques like Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) and Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP).

The existence of different sintering processes is not about variety for its own sake; it's about having a toolkit to solve specific material engineering challenges. The choice of method is a strategic decision that directly controls a final part's density, strength, microstructure, and cost.

The Fundamental Mechanisms of Bonding

The most basic way to classify sintering is by what happens at the particle level. The two foundational approaches are bonding particles in their solid form or using a small amount of liquid to accelerate the process.

Solid-State Sintering (The Conventional Method)

This is the most traditional form of sintering. Powdered material is compacted and then heated to a temperature just below its melting point.

At this high temperature, atoms diffuse across the boundaries of the particles, causing them to fuse together and gradually eliminate the pore spaces between them. This process is driven purely by the reduction of surface energy.

Liquid Phase Sintering (For Enhanced Density)

In this method, a small amount of a secondary material with a lower melting point is mixed with the main powder. When heated, this secondary material melts, creating a liquid phase that wets the solid particles.

This liquid accelerates densification by pulling particles together through capillary action and providing a fast path for atomic diffusion. The result is often a final part with very low porosity achieved at lower temperatures or in less time than solid-state sintering.

Reactive Sintering (Creating New Materials)

Reactive sintering, or reaction bonding, involves a chemical reaction between two or more different powder constituents during heating.

Instead of simply fusing existing particles, the process forms an entirely new chemical compound. This is a powerful method for creating advanced ceramics and intermetallic composites directly into a near-net shape.

Advanced Techniques: Controlling Heat and Pressure

To overcome the limitations of conventional methods, engineers have developed advanced techniques that use external pressure or alternative energy sources. These methods offer greater control over speed, temperature, and final material properties.

Pressure-Assisted Sintering (For Ultimate Density)

Applying external pressure during heating physically forces the particles together, dramatically accelerating densification. This is essential for materials that are difficult to sinter conventionally.

The two main types are Hot Pressing (HP), which applies pressure in one direction, and Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP), which applies high-pressure gas from all directions for uniform density. HIP is often used to produce critical, high-performance components with zero residual porosity.

Field-Assisted Sintering (For Speed and Microstructure)

Also known as Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS), this technique passes a pulsed DC electric current directly through the powder and the die. This creates extremely rapid heating from within the material itself.

The combination of pressure and rapid, localized heating allows for full densification in minutes instead of hours. This speed is critical for preserving nanoscale or other fine-grained microstructures, which are often essential for superior mechanical properties.

Microwave Sintering (For Energy Efficiency)

This method uses microwaves as the energy source. The microwaves heat the material volumetrically (from the inside out), in contrast to a conventional furnace which heats from the outside in.

This can lead to more uniform heating, faster processing cycles, and potential energy savings. It is particularly effective for certain ceramic materials that couple well with microwave energy.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Choosing a sintering process requires balancing competing factors. No single method is universally superior; each has a distinct profile of advantages and disadvantages.

Speed vs. Cost

Advanced methods like Spark Plasma Sintering and Microwave Sintering are significantly faster than conventional furnace heating. However, the specialized equipment they require represents a much higher capital investment. Conventional solid-state sintering remains the most cost-effective solution for high-volume production of less demanding parts.

Density vs. Grain Growth

Aggressive sintering conditions (high temperature, long duration) can achieve high density but often cause grain growth, where smaller grains merge into larger ones. This can be detrimental to mechanical properties like strength and hardness. Rapid processes like SPS are prized for their ability to achieve full density while suppressing grain growth, preserving a fine microstructure.

Complexity vs. Material Compatibility

Simple conventional sintering works for a wide range of materials. However, methods like SPS require the material to have some electrical conductivity. Liquid Phase Sintering requires finding a suitable additive that melts at the right temperature without negatively affecting the final properties.

Choosing the Right Sintering Process

Your choice of sintering process should be guided by the specific goals of your project and the nature of your material.

- If your primary focus is cost-effective mass production of standard parts: Conventional Solid-State Sintering is the established and economical choice.

- If your primary focus is achieving maximum density and eliminating all porosity for a critical component: Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) is the definitive solution.

- If your primary focus is rapid processing while preserving a fine-grained or nanostructured material: Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) is the leading technology.

- If your primary focus is creating a dense part from a powder mixture that forms a new compound: Reactive Sintering is the appropriate method.

Understanding these methods transforms sintering from a simple heating process into a precise tool for engineering advanced materials.

Summary Table:

| Sintering Process | Primary Mechanism | Key Advantage | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid-State Sintering | Atomic Diffusion | Cost-Effective | High-volume production of standard parts |

| Liquid Phase Sintering | Capillary Action | High Density | Achieving low porosity at lower temperatures |

| Reactive Sintering | Chemical Reaction | In-Situ Synthesis | Creating advanced ceramics and composites |

| Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) | Electric Current & Pressure | Speed & Microstructure Control | Preserving nanoscale grains, rapid densification |

| Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) | High-Pressure Gas | Zero Porosity | Critical, high-performance components |

| Microwave Sintering | Volumetric Heating | Energy Efficiency & Uniformity | Certain ceramics, faster processing cycles |

Ready to Optimize Your Sintering Process?

Choosing the right sintering method is critical to achieving the desired density, strength, and microstructure for your materials. At KINTEK, we specialize in providing advanced laboratory equipment and consumables to meet your specific sintering needs. Whether you are developing advanced ceramics, metal alloys, or complex composites, our expertise can help you:

- Select the ideal equipment (from conventional furnaces to advanced SPS systems) for your application.

- Achieve superior results with precise temperature and pressure control.

- Improve efficiency and reduce costs with energy-efficient and rapid processing solutions.

Let our experts guide you to the perfect solution for your lab. Contact KINTEK today for a personalized consultation!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace with 9MPa Air Pressure

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Heated Vacuum Press Machine Tube Furnace

- Spark Plasma Sintering Furnace SPS Furnace

- 600T Vacuum Induction Hot Press Furnace for Heat Treat and Sintering

- Dental Porcelain Zirconia Sintering Ceramic Vacuum Press Furnace

People Also Ask

- What are the advantages of vacuum sintering? Achieve Superior Purity, Strength, and Performance

- How does a vacuum environment system contribute to the hot pressing sintering of B4C-CeB6? Unlock Peak Ceramic Density

- What technical functions does a vacuum hot pressing sintering furnace provide? Optimize CoCrFeNi Alloy Coatings

- What are the primary advantages of using a vacuum hot pressing sintering furnace? Maximize Density in B4C-CeB6 Ceramics

- What are the advantages of using a vacuum hot pressing sintering furnace? Superior Density for Nanocrystalline Fe3Al