Introduction to Vacuum Evaporation

Definition and Advantages

Vacuum evaporation, commonly referred to as evaporation, is a process that occurs under vacuum conditions where a coating material, or film material, is heated to the point of gasification. This gaseous form of the material then particles fly towards a substrate surface where they condense and form a film. This technique is one of the earliest and most widely utilized methods in the field of vapor deposition.

The advantages of vacuum evaporation are manifold:

- Simplicity of Film Formation: The method is straightforward, requiring minimal complex equipment or procedures, making it accessible for various applications.

- High Purity and Densification: The films produced through vacuum evaporation exhibit high purity and density, which are critical for many industrial and scientific applications.

- Unique Film Structure and Performance: The films formed through this process often possess unique structural properties and performance characteristics that are distinct from those produced by other deposition techniques.

This method's simplicity, combined with the high quality of the films it produces, makes vacuum evaporation a cornerstone in the development of advanced materials and technologies.

Principles of Vacuum Evaporation

Physical Process

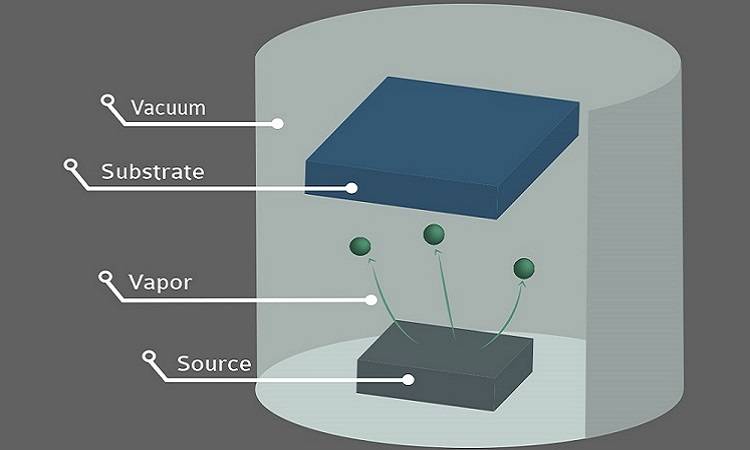

The physical process of vapor deposition involves several critical stages, each contributing to the formation of a high-quality thin film. Initially, the deposited material undergoes evaporation or sublimation, transforming into gaseous particles. This transformation typically occurs under controlled vacuum conditions, where the material is heated to its vaporization point. The energy required for this phase transition can be supplied through various methods, such as resistance heating, electron beam heating, or laser heating.

Once the material has been converted into gaseous particles, these particles undergo rapid transport from the evaporation source to the surface of the substrate. In the vacuum environment, the gaseous particles move in a nearly collision-free manner, ensuring a direct and efficient transfer to the substrate. This rapid transport minimizes the likelihood of particle recombination or reaction with residual gases, thereby maintaining the purity and integrity of the deposited material.

Upon reaching the substrate, the gaseous particles nucleate and grow on the surface. This process involves the adsorption of particles onto the substrate, followed by surface diffusion and the formation of clusters. The nucleation process is crucial as it determines the initial structure and density of the thin film. As more particles attach to the growing clusters, the film begins to form a continuous layer.

Finally, the thin film undergoes reconfiguration as the atoms within the film rearrange themselves to achieve a more stable configuration. This reconfiguration can also involve the generation of chemical bonds, enhancing the adhesion and cohesion of the film to the substrate. The final structure of the thin film is influenced by factors such as the deposition rate, substrate temperature, and the energy of the incoming particles.

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Evaporation/Sublimation | Material transforms into gaseous particles under controlled vacuum conditions. |

| Rapid Transport | Gaseous particles move efficiently to the substrate in a collision-free manner. |

| Nucleation and Growth | Particles adsorb onto the substrate, diffuse, and form clusters to create a film. |

| Reconfiguration | Film atoms rearrange to form a stable structure, possibly involving chemical bonding. |

Components of Vacuum Evaporation Systems

Vacuum System

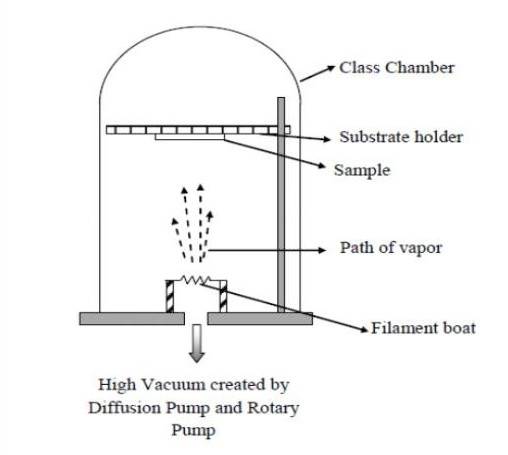

The substrate is securely placed within a vacuum chamber, where the film material undergoes heating through various methods such as resistance, electron beam, or laser. This heating process causes the film material to evaporate or sublimate, transforming it into gaseous particles. These particles, consisting of atoms, molecules, or clusters of atoms, possess a specific amount of energy, typically ranging from 0.1 to 0.3 eV.

The vacuum system is crucial for maintaining the necessary conditions within the chamber. It operates in the 10-2 Torr range, facilitated by a two-stage rotary vane pump. Additional components, such as a vacuum gauge controller with a vacuum gauge, electro-pneumatic vacuum valve, and vacuum air release and leak check valves, ensure precise control and monitoring of the vacuum environment.

Moreover, the system can be configured to operate with inert gases like Argon, Nitrogen, Helium, or non-flammable forming gas, with a standard positive pressure of 2 PSIG (0.14 Bar). A relief valve and a compound gauge (30 PSIG x 30in. Hg) are strategically placed on the vacuum chamber to maintain safety and operational integrity.

For specialized applications, options such as a Flow Adapter Kit for continuous flow with gas windows in a horizontal configuration, or a partial pressure control system, are available to enhance the system's versatility and efficiency.

Evaporation System

In the context of vacuum evaporation, the evaporation system plays a pivotal role in the deposition process. Gaseous particles, generated from the evaporation source, travel in a near collision-free linear motion towards the substrate. Upon reaching the substrate surface, these particles undergo a series of interactions: a portion of them are reflected, while others are adsorbed onto the substrate. Once adsorbed, these particles undergo surface diffusion, leading to the formation of clusters through two-dimensional atomic collisions. Notably, some of these clusters may temporarily reside on the surface before eventually evaporating, contributing to the dynamic nature of the deposition process.

The Cole-Parmer evaporator system exemplifies a sophisticated setup designed to simplify both setup and operation. This complete system includes a rotational evaporator equipped with a computerized water bath, a mechanical lift, and a standard glassware set. The brushless high-force motor ensures steady rotation at variable speeds, ranging from 20 to 180 rpm, while vertical condensers maximize bench vacuum efficiency. The computerized water bath operates within a temperature range of ambient to 90°C, featuring heating loops beneath the dish surface and an integrated overheat defender to safeguard against controller failures. The standard glassware set comprises a 1-L pear-shaped evaporating flask, a 1-L round-bottomed receiving cup, and a condenser, providing a comprehensive toolkit for precise evaporation processes.

Evaporation Source

The evaporation source is a critical component in the vacuum evaporation process, serving as the origin from which the deposition material is vaporized and subsequently deposited onto the substrate. The shape of the evaporation source can vary significantly, with common configurations including spiral (a), basket (b), hair fork (c), and shallow boat (d). Each shape is designed to optimize the distribution and uniformity of the evaporated material across the substrate.

When selecting an evaporation source material, several key criteria must be considered:

- High Melting Point: The material should have a melting point far exceeding the evaporation temperature to ensure stability during the process.

- Minimal Contamination: The evaporation temperature of the film material should be lower than the temperature at which the evaporation source material reaches a vapor pressure of 10^-8 Torr, minimizing contamination.

- Chemical Stability: The evaporation source material must not react with the film material to prevent any adverse chemical interactions.

- Wettability: The film material should exhibit good wettability with the evaporation source to facilitate uniform film formation.

Commonly used evaporation source materials include tungsten (W), molybdenum (Mo), tantalum (Ta), high-temperature resistant metal oxides, and ceramic or graphite crucibles. These materials are chosen for their ability to withstand high temperatures without degrading, ensuring the purity and quality of the deposited film.

In summary, the evaporation source is not just a simple container but a carefully designed and selected component that plays a pivotal role in the vacuum evaporation process, influencing the quality and properties of the final thin film.

Advanced Techniques in Vacuum Evaporation

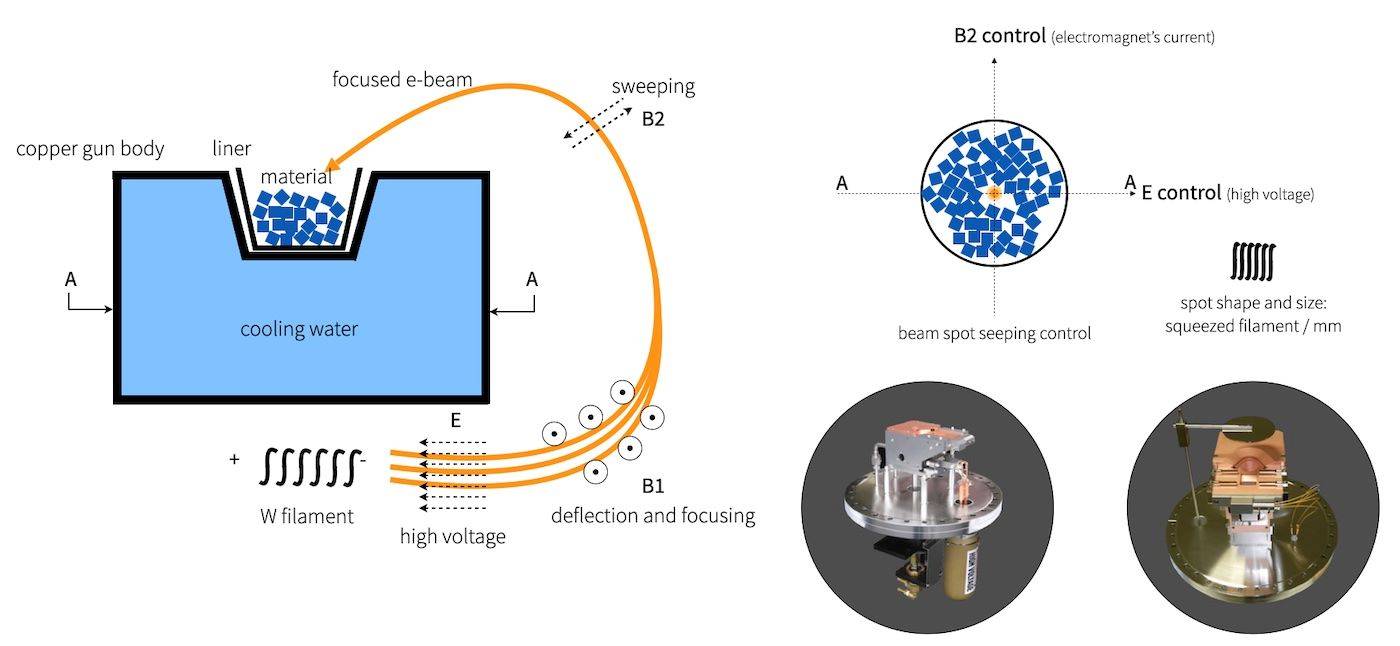

Electron Beam Evaporation

Electron beam evaporation is a sophisticated technique used to deposit materials with high melting points, such as tungsten and tantalum, onto a substrate. This method employs a focused electron beam to heat and evaporate the target material directly. The electron beam, typically accelerated by a 100 kV DC voltage source, attains temperatures around 3000 °C before striking the material to be evaporated. This high-energy impact converts the kinetic energy of the electrons into thermal energy, causing the material to melt and vaporize at a highly localized point near the beam's impact site.

One of the key advantages of electron beam evaporation is its ability to prevent contamination. The material to be evaporated remains in a solid state within a heavy, water-cooled copper crucible, minimizing the risk of chemical reactions between the evaporated material and the crucible. This setup ensures that the resulting film is of high purity. Additionally, the thermal electron emission process, where electrons within the metal gain enough energy to escape its surface at high temperatures, further enhances the efficiency and precision of the evaporation process.

The electron beam's energy is rapidly dissipated upon striking the source material, with some of it being lost through the production of X-rays and secondary electron emission. Despite these energy losses, the majority is effectively converted into thermal energy, sufficiently heating the source surface to produce vapor that coats the substrate. This method is particularly effective for applications requiring high-purity, dense films, such as in optics, electronics, and photonics.

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Temperature | Electrons are heated to around 3000 °C before striking the material. |

| Acceleration | Accelerated by a 100 kV DC voltage source. |

| Localization | Evaporation occurs at a highly localized point near the beam impact site. |

| Contamination Prevention | Material remains solid in a water-cooled crucible, minimizing reaction risks. |

| Energy Conversion | Kinetic energy of electrons converted into thermal energy upon impact. |

| Applications | Suitable for high-purity, dense film preparation in optics, electronics, etc. |

The complexity and cost of electron beam evaporation systems, along with potential ionization of evaporation gases and residual gases, are notable disadvantages. However, the benefits of high-purity, dense film deposition make it a valuable technique in various industrial and research applications.

Characteristics and Disadvantages

Electron beam evaporation systems are renowned for their ability to evaporate refractory materials efficiently. This is achieved through high power density, which ensures rapid evaporation and prevents alloy fractionation. These systems can accommodate multiple crucibles, allowing for the simultaneous or separate evaporation of various materials, thereby enhancing versatility. The majority of E-beam evaporation systems employ a magnetically focused or bent electron beam, with the evaporated material housed in a water-cooled crucible. This configuration ensures that the evaporation process occurs on the surface of the material, effectively inhibiting any reaction between the crucible and the evaporated material. This method is particularly suitable for the preparation of high-purity thin films, which are essential in fields such as optics, electronics, and photonics. Materials commonly processed include Mo, Ta, Nb, MgF2, Ga2Te3, TiO2, Al2O3, SnO2, and Si.

The evaporated molecules possess higher kinetic energy compared to those produced by resistance heating, resulting in more robust and denser film layers. However, electron beam evaporation sources are not without their drawbacks. One significant disadvantage is their tendency to ionize evaporation gases and residual gases, which can sometimes compromise the quality of the film layer. Additionally, the structural complexity of these devices contributes to their high cost. Furthermore, the soft X-rays produced during the process pose a certain degree of harm to human health, necessitating stringent safety measures.

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Efficient evaporation of refractory materials | Ionization of evaporation gases and residual gases |

| High power density for rapid evaporation | Structural complexity and high cost |

| Multiple crucible placement for versatility | Production of soft X-rays harmful to human health |

| Inhibition of crucible-material reaction | |

| High-purity thin film preparation | |

| Enhanced kinetic energy for denser film layers |

Related Products

- Laboratory Benchtop Water Circulating Vacuum Pump for Lab Use

- Vacuum Induction Melting Spinning System Arc Melting Furnace

- Lab-Scale Vacuum Induction Melting Furnace

- Ceramic Evaporation Boat Set Alumina Crucible for Laboratory Use

- Inclined Rotary Plasma Enhanced Chemical Vapor Deposition PECVD Equipment Tube Furnace Machine

Related Articles

- Exploring the Science Behind Rotary Evaporators: How They Work and Their Applications

- Step-by-Step Guide to Operating a Short Path Distillation Apparatus

- Choosing the Right Rotary Vacuum Evaporator for Your Lab

- How to Choose and Optimize Water Circulating Vacuum Pumps for Your Lab

- A Step-by-Step Guide to Using a Rotary Vacuum Evaporator for Solvent Removal