High-pressure reactors and Zinc Chromite catalysts worked in tandem as the "muscle and mechanism" behind the first industrial-scale production of methanol. The reactors provided the extreme physical force necessary to make the reaction thermodynamically favorable, while the catalyst enabled the chemical transformation of carbon monoxide and hydrogen at the required speed and temperature.

Core Takeaway This early approach represents a "brute force" engineering solution to thermodynamic limitations. By combining massive compression (>300 atm) with a robust, heat-tolerant catalyst, engineers prioritized the sheer feasibility of large-scale production over energy efficiency.

Overcoming Thermodynamic Barriers

The Role of Extreme Pressure

The primary function of the high-pressure reactor was to manipulate the thermodynamic equilibrium of the reaction.

Converting carbon monoxide and hydrogen into methanol is a process that naturally limits itself at lower pressures. To force the gases to combine efficiently, the system required an environment exceeding 300 atmospheres (atm).

Shifting the Equilibrium

At these extreme pressures, the reactor effectively "squeezed" the reactants together.

This overcame the natural tendency of the chemicals to remain apart, shifting the thermodynamic balance toward the formation of liquid methanol. Without this pressure, industrial yields would have been negligible.

The Role of the Zinc Chromite Catalyst

Enabling the Chemical Bond

While pressure created the right environment, the Zinc Chromite catalyst was the engine that drove the actual chemistry.

It served as the core active material, facilitating the "addition reaction." It lowered the activation energy required for carbon monoxide and hydrogen to bond effectively.

Operating at High Temperatures

Crucially, Zinc Chromite was selected for its robustness.

To achieve acceptable reaction rates, the process required high temperatures. Zinc Chromite remained stable and active under these thermal conditions, unlike other potential materials that might degrade or lose effectiveness in such a harsh environment.

Understanding the Trade-offs

High Energy Consumption

The most significant drawback of this method was its energy intensity.

Compressing gases to pressures exceeding 300 atm requires massive amounts of mechanical energy. This made the operational costs of early methanol plants extremely high compared to modern standards.

Equipment Stress and Complexity

Operating at such extremes placed immense physical stress on the infrastructure.

The reactors had to be built with heavy, thick-walled steel to contain the pressure, increasing the capital cost and complexity of construction and maintenance.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

While this technology has largely been superseded by more efficient low-pressure processes, understanding its principles is vital for grasping chemical engineering evolution.

- If your primary focus is historical analysis: Recognize that this method established methanol as a viable bulk commodity, paving the way for the downstream chemical industry.

- If your primary focus is process design: Note how catalyst selection (Zinc Chromite) dictated the operating conditions (High P/High T), proving that material science often defines process parameters.

The legacy of this early technology demonstrates that in industrial chemistry, feasibility often precedes efficiency.

Summary Table:

| Component | Primary Role | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| High-Pressure Reactor | Manipulates thermodynamic equilibrium | Operates at >300 atm pressure |

| Zinc Chromite Catalyst | Lowers activation energy & drives chemistry | High thermal stability & robustness |

| Pressure Dynamics | Forces reactant gases to combine | Overcomes natural chemical repulsion |

| Thermal Context | Increases reaction speed | Requires heat-tolerant catalyst materials |

Elevate Your Chemical Engineering with KINTEK Precision

Are you looking to replicate complex chemical processes or push the boundaries of material synthesis? KINTEK specializes in providing the high-performance laboratory equipment and consumables essential for modern research and industrial scale-up.

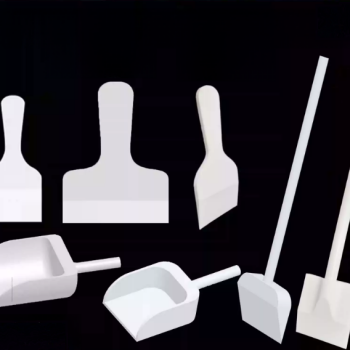

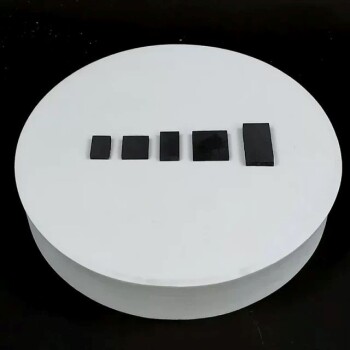

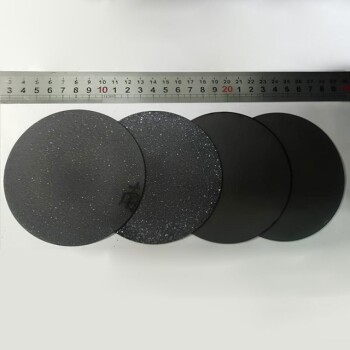

From high-temperature high-pressure reactors and autoclaves designed to withstand extreme environments to our specialized crushing and milling systems and PTFE products, we provide the tools necessary to bridge the gap between feasibility and efficiency. Whether you are conducting catalyst research with our electrolytic cells or managing thermal cycles with our cooling solutions, KINTEK ensures your lab is equipped for success.

Take the next step in your process design—contact us today to discover our comprehensive range of laboratory solutions tailored for your target applications!

References

- Mark A. Murphy. The Emergence and Evolution of Atom Efficient and/or Environmentally Acceptable Catalytic Petrochemical Processes from the 1920s to the 1990s. DOI: 10.36253/substantia-3100

This article is also based on technical information from Kintek Solution Knowledge Base .

Related Products

- Stainless High Pressure Autoclave Reactor Laboratory Pressure Reactor

- Customizable Laboratory High Temperature High Pressure Reactors for Diverse Scientific Applications

- High Pressure Laboratory Autoclave Reactor for Hydrothermal Synthesis

- Mini SS High Pressure Autoclave Reactor for Laboratory Use

- Laboratory High Pressure Horizontal Autoclave Steam Sterilizer for Lab Use

People Also Ask

- What is the function of high-pressure reactors and autoclaves in HTL? Unlocking Efficient Bio-Fuel from Wet Microalgae

- What is the purpose of using high-purity argon gas in a high-pressure reactor? Ensure Precise Corrosion Test Data

- How does a high-pressure reactor demonstrate its value in accelerated aging? Predict Catalyst Durability Fast

- What is the role of a high-pressure reactor in hydrothermal synthesis? Optimize Mesoporous Hydroxyapatite Production

- Why are sealed laboratory reaction vessels necessary in the hydrothermal synthesis of zeolites? Ensure Purity and Yield