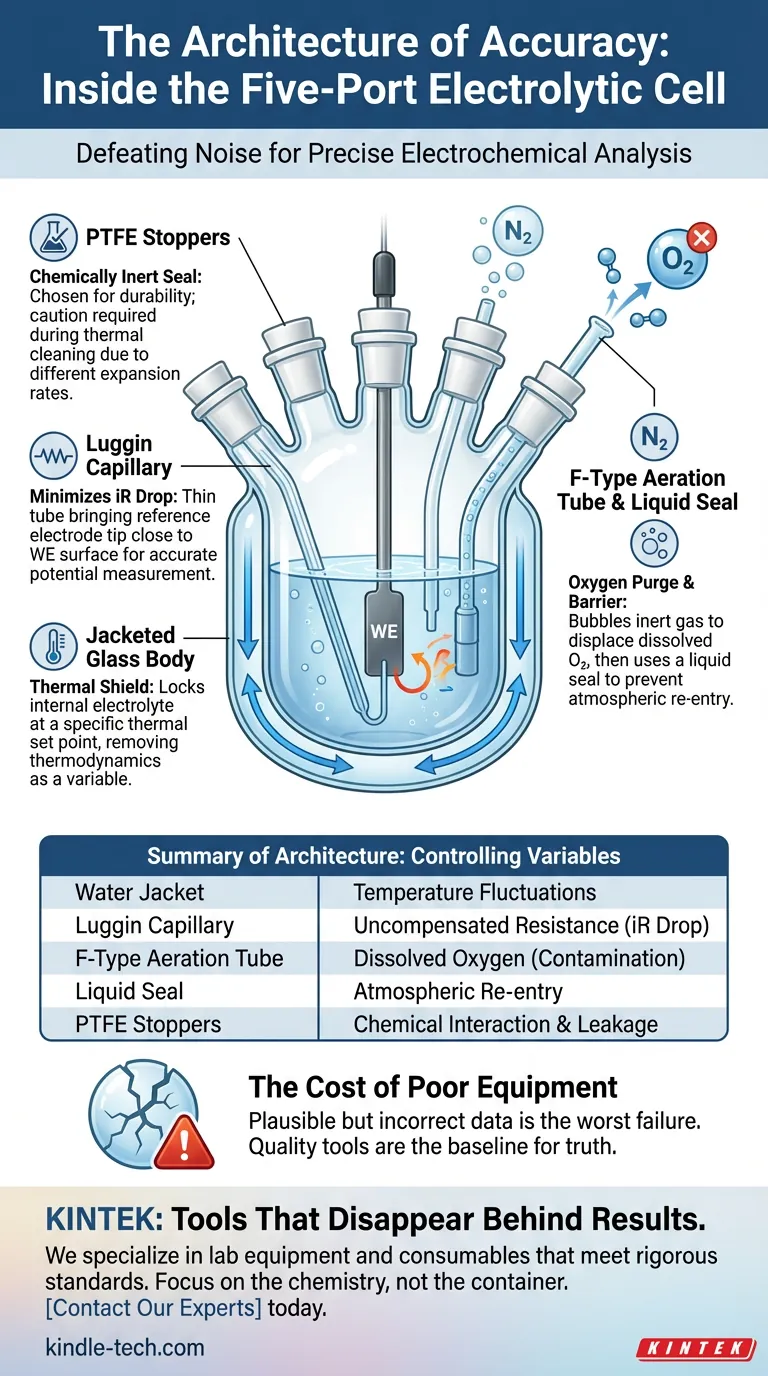

Science is often portrayed as a battle of intellects. In the laboratory, however, it is primarily a battle against variables.

In electrochemical analysis, the enemy is noise. It is the fluctuation of temperature, the intrusion of oxygen, and the invisible resistance within the solution itself. To defeat these enemies, we build fortresses.

The five-port water bath electrolytic cell is not merely a glass container. It is a carefully engineered system designed to isolate a reaction from the chaos of the outside world.

It allows researchers to create a "perfect" micro-environment. But like any precision instrument, its effectiveness depends entirely on understanding the architecture of its parts.

Here is the anatomy of a controlled experiment.

The Foundation: The Jacketed Glass Body

Most errors in chemistry are thermal errors.

Reaction rates change with temperature. Viscosity changes. Conductivity changes. If your lab gets warmer in the afternoon than it was in the morning, your data will drift.

The standard cell body solves this through a double-walled water jacket.

By circulating fluid from a temperature-controlled bath through this outer jacket, the internal electrolyte is locked at a specific thermal set point. It creates a thermal shield, rendering the ambient temperature of the room irrelevant.

It is a simple design with a profound impact: it removes thermodynamics as a variable.

The Bridge: The Luggin Capillary

In a three-electrode system, accurate potential measurement is the goal.

However, there is a physical reality that often gets in the way: iR drop. This is the voltage error caused by the resistance of the solution and the current flowing through it.

If your reference electrode is too far from your working electrode, you aren't measuring the interface; you are measuring the resistance of the path between them.

The Luggin capillary is the engineer’s solution to this physical constraint.

- The Design: A thin glass tube that extends the path of the reference electrode.

- The Function: It allows the sensing tip to sit extremely close to the working electrode surface.

- The Result: It minimizes uncompensated resistance without blocking the current path.

It is a delicate balance. Too far, and you lose accuracy. Too close, and you shield the surface. The Luggin capillary allows you to find the perfect middle ground.

The Gatekeeper: Aeration and Sealing

Oxygen is the great contaminate. It is electrochemically active and omnipresent. For many reduction reactions, dissolved oxygen appears as a ghost signal, obscuring the data you are actually trying to find.

The cell uses a two-part system to purge the environment and keep it pure.

1. The F-Type Aeration Tube

This acts as the purge mechanism. Before the experiment begins, inert gas (like Nitrogen or Argon) is bubbled through the solution via this tube. It physically displaces the dissolved oxygen.

2. The Liquid Seal

Once the oxygen is out, the challenge is keeping it out. The liquid seal acts as a one-way valve. It allows the inert gas to blanket the solution and exit the cell, but creates a barrier that atmospheric oxygen cannot cross against.

The Containment: PTFE Stoppers

The final component is the seal. The ports are typically closed with Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) stoppers.

PTFE is chosen for its chemical inertness. It does not react, degrade, or contaminate the sample. However, it introduces a mechanical constraint that often trips up new researchers.

The Thermal Trap: Glass and PTFE expand at different rates when heated.

If you place the entire assembly—glass body and PTFE stoppers—into an autoclave or oven, the plastic will expand faster than the glass. This leads to deformed stoppers and ruined seals.

The system is designed for chemical durability, not thermal abuse during cleaning.

Summary of Architecture

Every part of the cell exists to control a specific variable.

| Component | The Variable it Controls |

|---|---|

| Water Jacket | Temperature fluctuations |

| Luggin Capillary | Uncompensated resistance (iR drop) |

| F-Type Aeration Tube | Dissolved Oxygen (Contamination) |

| Liquid Seal | Atmospheric re-entry |

| PTFE Stoppers | Chemical interaction and leakage |

The Cost of Poor Equipment

In high-stakes research, equipment is not a cost center; it is the baseline for truth.

A crack in a Luggin capillary or a leaking seal doesn't just look bad—it yields plausible but incorrect data. That is the worst kind of failure in science.

At KINTEK, we believe that the tools should disappear behind the results. We specialize in lab equipment and consumables that meet the rigorous standards of modern electrochemistry. From precision glass bodies to durable PTFE accessories, our goal is to provide the reliability you need to focus on the chemistry, not the container.

Contact Our Experts today to discuss your experimental setup and ensure your laboratory is built for accuracy.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

- Double Layer Five-Port Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Optical Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- H-Type Double-Layer Optical Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Water Bath

Related Articles

- The Silent Dialogue: Mastering Control in Electrolytic Cells

- The Fragile Vessel of Truth: A Maintenance Manifesto for Electrolytic Cells

- The Fragility of Precision: Mastering the Integrity of Five-Port Electrolytic Cells

- The Invisible Architecture of Accuracy: Optimizing the Five-Port Electrolytic Cell

- The Architecture of Precision: Mastering the Five-Port Water Bath Electrolytic Cell