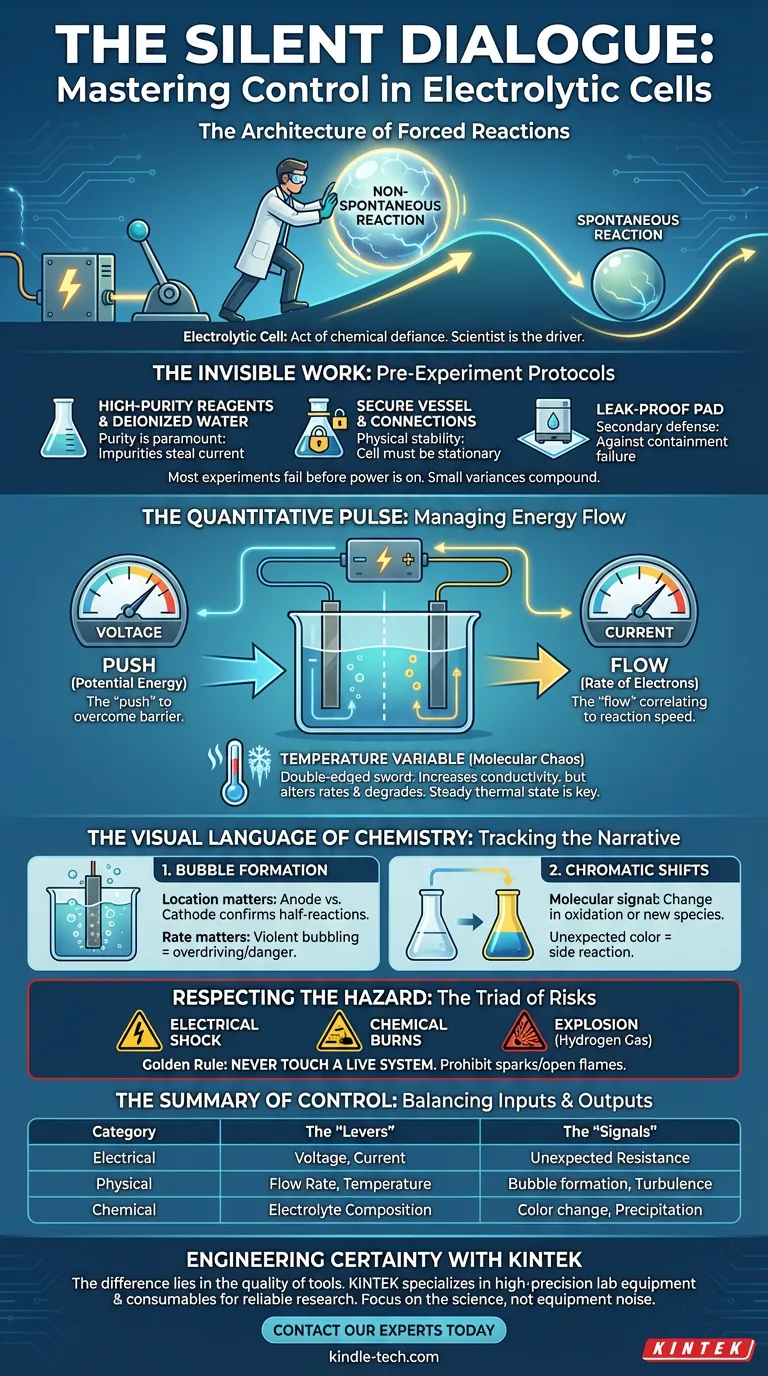

The Architecture of Forced Reactions

In chemistry, most reactions we study are eager to happen. They are spontaneous, sliding down the energy hill like a ball rolling into a valley.

Electrolysis is different.

An electrolytic cell is an act of chemical defiance. You are using electrical energy to push a reaction uphill, forcing nature to do something it would prefer not to do. Because this process is non-spontaneous, the system is constantly looking for a way to stop—or worse, to find a chaotic, lower-energy alternative path.

This makes the role of the scientist fundamentally different. You are not a passive observer; you are the driver.

Success in this environment doesn't come from merely collecting data. It comes from mastering the feedback loop between the quantitative parameters you control and the qualitative phenomena the system reveals.

The Invisible Work: Pre-Experiment Protocols

Most failed experiments fail before the power supply is even turned on.

In complex systems, small initial variances compound into large final errors. A slight impurity in the water or a loose electrode connection introduces variables that mathematics cannot account for later.

To ensure the integrity of the process:

- Purity is paramount: Use high-purity reagents and deionized water. Impurities are not just dirt; in electrochemistry, they are competing reactants that steal current and skew results.

- Physical stability: The cell must be stationary. Secure the vessel and tighten fixing knobs.

- The secondary defense: If using corrosive electrolytes, a leak-proof pad isn't paranoia—it is a necessary redundancy against containment failure.

The Quantitative Pulse

Once the experiment begins, you are managing energy flow. There are two primary levers at your disposal, and they tell you very different things.

Voltage and Current

Voltage is the "push"—the potential energy required to overcome the thermodynamic barrier of the reaction. Current is the "flow"—the rate at which electrons are moving, directly correlating to how fast the chemical conversion is happening.

If you are optimizing for efficiency, these numbers are your north star. However, they must be viewed in context. A sudden drop in current at constant voltage often signals that your electrode surface has become passivated or depleted.

The Temperature Variable

Temperature is the measure of molecular chaos. In electrolysis, it is a double-edged sword.

Heat increases conductivity, which can be beneficial. However, it also alters reaction rates and can degrade the electrolyte. Uncontrolled temperature fluctuations are the enemy of reproducibility. A steady thermal state is the hallmark of a controlled experiment.

The Visual Language of Chemistry

While sensors track the numbers, your eyes must track the narrative. The electrolytic cell communicates its status through physical phenomena that digital displays often miss.

1. Bubble Formation

The generation of bubbles on an electrode is the heartbeat of many electrolytic processes.

- Location matters: Bubbles at the anode vs. the cathode confirm which half-reaction is occurring where.

- Rate matters: Violent bubbling may indicate you are overdriving the cell, potentially damaging the electrode surface or creating safety hazards.

2. Chromatic Shifts

A solution changing color is a molecular signal. It indicates a change in oxidation state or the birth of a new chemical species.

If the solution turns a color you didn't predict, the system is telling you that a side reaction—an "unintended path"—has opened up. This is immediate, qualitative feedback that requires your attention.

Respecting the Hazard

Because we are forcing energy into a system, the potential for energetic release is real.

Electrolysis carries a unique triad of risks: Electrical shock (from the power source), Chemical burns (from corrosive electrolytes), and Explosion (from accumulated hydrogen gas).

The golden rule of the electrolytic lab is simple: Never touch a live system. The separation between the operator and the electrode is the margin of safety. Furthermore, the generation of flammable gases demands a strict prohibition of sparks or open flames.

The Summary of Control

To master the electrolytic cell, one must balance the inputs with the observed outputs.

| Category | The "Levers" (What you set) | The "Signals" (What you see) |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical | Voltage, Current | unexpected Resistance |

| Physical | Flow Rate, Temperature | Bubble formation, Turbulence |

| Chemical | Electrolyte Composition | Color change, Precipitation |

Engineering Certainty

The difference between a dangerous experiment and a breakthrough often lies in the quality of the tools used to mediate this energy.

At KINTEK, we understand that in the dialogue between scientist and chemistry, there is no room for equipment noise. We specialize in the high-precision lab equipment and consumables that form the backbone of reliable research. From stable power supplies to durable, corrosion-resistant cells, our products are designed to disappear into the background, letting you focus on the science.

Contact our experts today to secure the equipment that gives you total control over your electrolytic processes.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

- Quartz Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Electrochemical Experiments

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- H-Type Double-Layer Optical Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Water Bath

Related Articles

- The Architecture of Precision: Mastering Electrolytic Cell Maintenance

- The Transparency Paradox: Mastering the Fragile Art of Electrolytic Cells

- The Symphony of Coefficients: Why Your Electrolytic Cell Cannot Be a Monolith

- The Architecture of Precision: Mastering the Five-Port Water Bath Electrolytic Cell

- The Silent Variable: Engineering Reliability in Electrolytic Cells