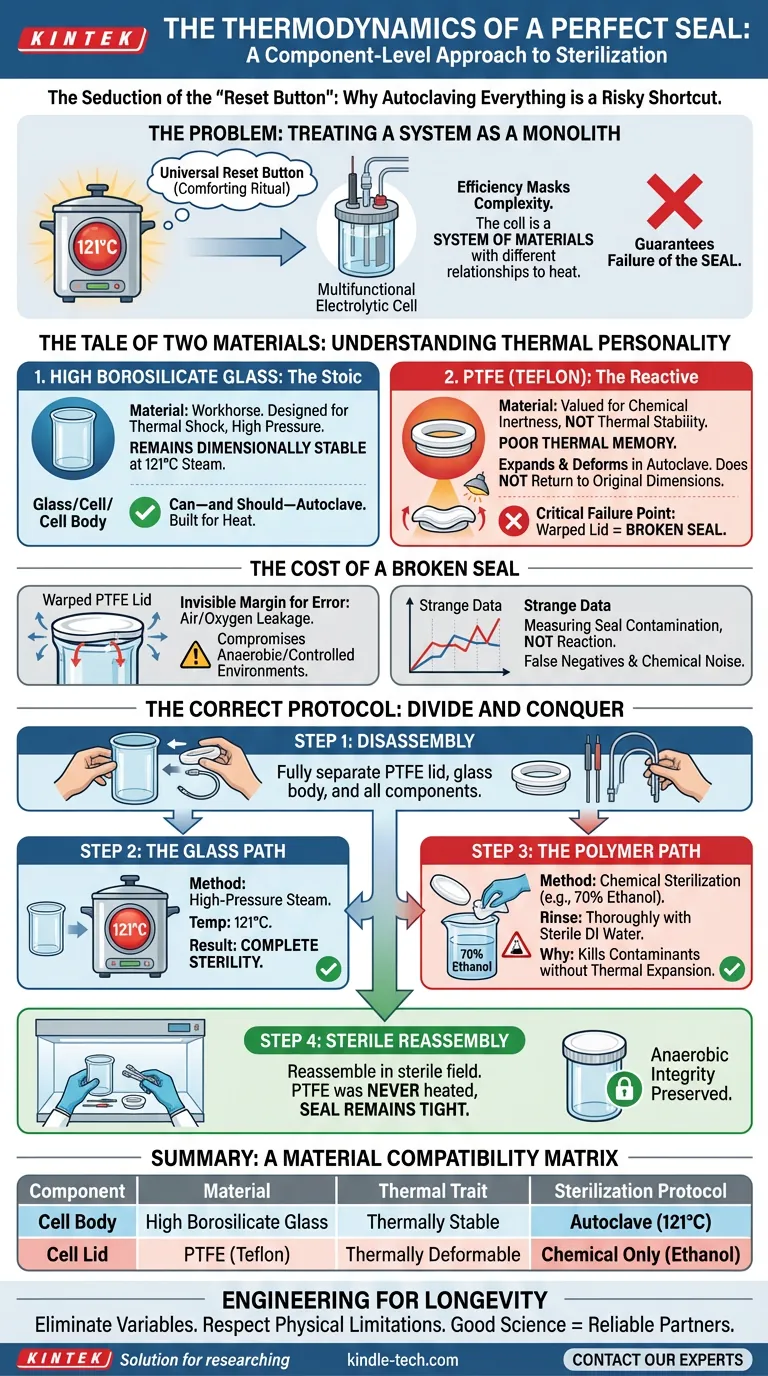

The Seduction of the "Reset Button"

In the laboratory, the autoclave is often viewed as a universal reset button.

It creates a sense of safety. You put equipment in, run a cycle at 121°C, and pull it out sterile. It is a comforting ritual of efficiency.

However, efficiency in science often masks complexity. When we treat a multifunctional electrolytic cell as a single object, we are making a category error. The cell is not one object; it is a system of materials with vastly different relationships to heat.

Treating the system as a monolith doesn't just risk damaging the equipment. It guarantees the failure of the experiment’s most critical requirement: the seal.

The Tale of Two Materials

To preserve the integrity of your research, you must understand the "thermal personality" of the two primary components in your cell.

1. High Borosilicate Glass: The Stoic

The body of the cell is engineered from high borosilicate glass.

This material is the workhorse of the chemical world. It is designed for thermal shock. It handles high pressure. When exposed to 121°C steam, it remains dimensionally stable.

You can—and should—autoclave the glass body. It is built for the heat.

2. PTFE (Teflon): The Reactive

The lid, however, is typically made of Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE).

We value PTFE for its chemical inertness, not its thermal stability. Under the intense heat of an autoclave, PTFE undergoes significant thermal expansion.

Here is the critical engineering failure point: PTFE has poor thermal memory.

When it expands in the autoclave, it deforms. Upon cooling, it does not return to its original micrometric dimensions. The lid warps. The threading shifts.

The result? A lid that fits onto the cell but no longer seals the cell.

The Cost of a Broken Seal

The damage to a PTFE lid is rarely catastrophic in appearance. It might look fine to the naked eye.

But in electrochemistry, the margin for error is invisible.

A deformed lid fails to create an airtight seal with the glass body. If your experiment requires an anaerobic environment or a controlled atmosphere, that environment is compromised the moment you close the lid.

You are no longer measuring the reaction of your electrolyte; you are measuring the contamination of your seal.

The Correct Protocol: Divide and Conquer

The solution requires a shift in mindset. You must stop sterilizing the unit and start sterilizing the components.

Here is the component-specific workflow:

Step 1: Disassembly

The cell must be fully disassembled. Separate the PTFE lid from the glass body. Remove electrodes and tubing.

Step 2: The Glass Path

Place the high borosilicate glass body into the autoclave.

- Method: High-pressure steam.

- Temp: 121°C.

- Result: Complete sterility.

Step 3: The Polymer Path

Treat the PTFE lid chemically.

- Method: Chemical sterilization (e.g., 70% ethanol immersion or wipe).

- Rinse: Thoroughly rinse with sterile deionized water.

- Why: This kills contaminants without triggering thermal expansion.

Step 4: Sterile Reassembly

Reassemble the components in a laminar flow hood or sterile field. Because the PTFE was never heated, the seal remains tight, and the anaerobic integrity is preserved.

The Risks of Shortcuts

Why do researchers still autoclave the whole unit? Because it is faster.

But consider the hidden risks of this "shortcut":

- Equipment Attrition: A warped lid renders the entire cell unusable. The cost of replacement far exceeds the time saved.

- The "False Negative": You may run an experiment assuming the cell is sealed, only to get strange data caused by oxygen leakage. You blame the chemistry, but the culprit was the physics of the lid.

- Chemical Noise: If you choose chemical sterilization for the lid but fail to rinse it properly, residual ethanol can alter electrochemical signals.

Summary: A Material Compatibility Matrix

| Component | Material | Thermal Trait | Sterilization Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Body | High Borosilicate Glass | Thermally Stable | Autoclave (121°C) |

| Cell Lid | PTFE (Teflon) | Thermally Deformable | Chemical Only (Ethanol) |

Engineering for Longevity

Good science is about eliminating variables. By respecting the physical limitations of your equipment materials, you eliminate the variable of mechanical failure.

At KINTEK, we design our laboratory equipment to withstand the rigors of research, but we also believe in empowering scientists with the knowledge to use them correctly. A well-maintained electrolytic cell is not just a tool; it is a reliable partner in your discovery process.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Portable Digital Display Automatic Laboratory Sterilizer Lab Autoclave for Sterilization Pressure

- Portable High Pressure Laboratory Autoclave Steam Sterilizer for Lab Use

- Laboratory High Pressure Steam Sterilizer Vertical Autoclave for Lab Department

- Laboratory High Pressure Horizontal Autoclave Steam Sterilizer for Lab Use

- Laboratory Sterilizer Lab Autoclave Pulsating Vacuum Desktop Steam Sterilizer

Related Articles

- 10 Essential Safety Steps for Pressure Reactor Use in Laboratories

- Laboratory Safety: High Pressure Equipment and Reactors

- Basic Cleaning and Disinfection Equipment in the Laboratory

- Manual Pellet Press: A Comprehensive Guide to Efficient Lab Pelletizing

- Comprehensive Overview of Warm Isostatic Press and Its Applications