The Silence After the Data

There is a specific kind of exhaustion that hits after a long electrochemical experiment. The data is collected. The curves have been plotted. The hum of the potentiostat dies down.

In this moment, the temptation is human and overwhelming: to turn off the lights, walk away, and deal with the cleanup tomorrow.

This is the most dangerous moment for your research.

We often think of science as the active moments—the mixing, the reacting, the measuring. But the integrity of your next experiment is entirely dependent on how you treat the silence of the current one.

An all-quartz electrolytic cell is not merely a container. It is a precision optical instrument. It provides the invisible stage upon which your chemistry performs. If that stage is dirty, the performance is compromised.

Here is why the ritual of cleanup matters, and how to execute it with the precision of an engineer.

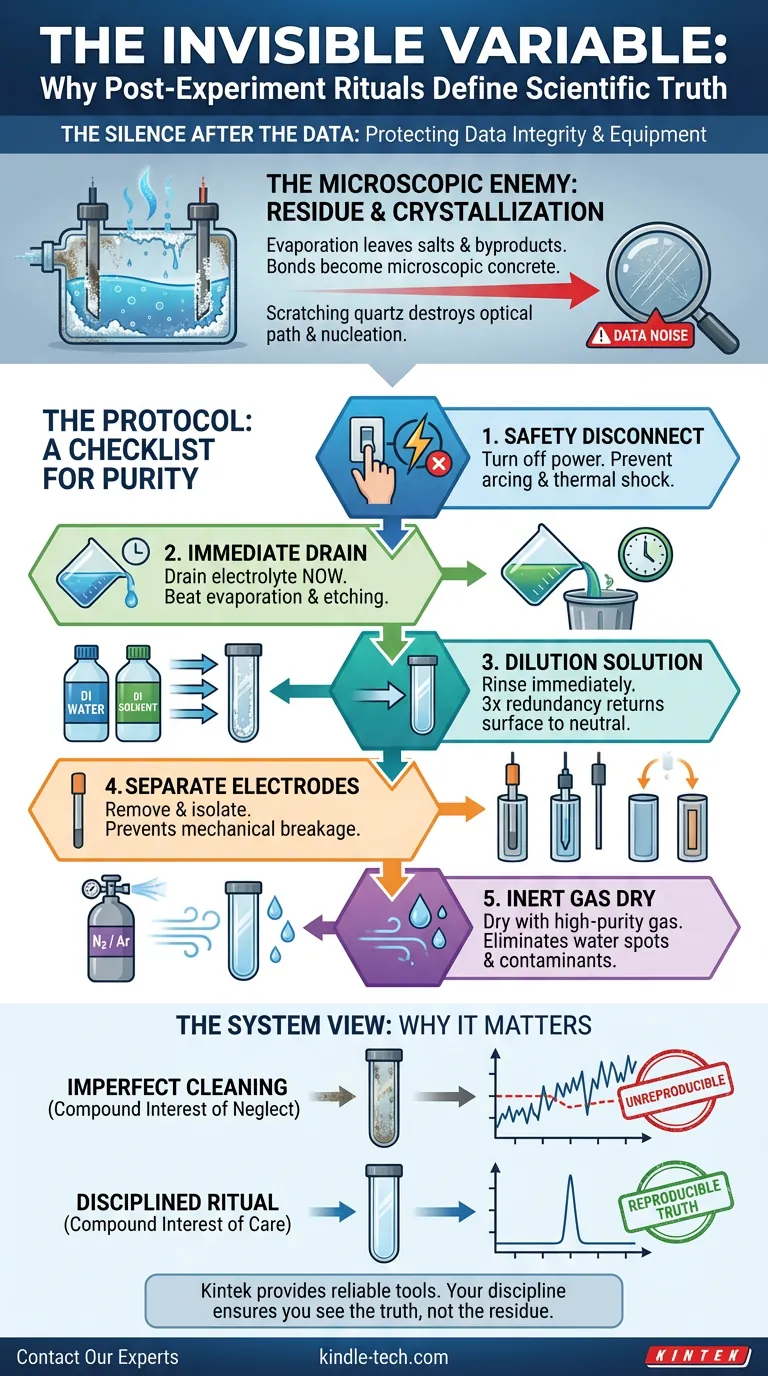

The Microscopic Enemy: Crystallization

The enemy of reproducibility is residue.

When you leave an electrolyte solution in a quartz cell, evaporation begins immediately. As the solvent leaves, salts and reaction byproducts remain. They do not just sit on the surface; they bond to it.

Once these crystals form and dry, they become microscopic concrete. Removing them later requires harsh measures—abrasive scrubbing or strong acids—that quartz, for all its thermal resilience, hates.

Quartz is brittle. It is susceptible to micro-scratches.

A scratch on a beaker is an annoyance. A scratch on an electrolytic cell is a disruption in the optical path and a potential nucleation site for unwanted bubbles.

The "cleanup" is actually a preservation strategy for your financial investment and your data integrity.

The Protocol: A Checklist for Purity

Atul Gawande famously argued that in complex environments, memory fails. We need checklists.

Treating your quartz cell requires a systematic protocol, executed the same way every time. This removes the variable of human error from your lab work.

1. The Safety Disconnect

The first step is silence. Turn off the power source.

Disconnecting a live cell risks electric arcs. An arc can damage the sensitive electrode connections or, in worst-case scenarios, shatter the quartz due to thermal shock. Safety is the baseline of all procedure.

2. The Race Against Time

Drain the electrolyte immediately.

Do not wait for lunch. Do not answer an email. The moment the experiment ends, the fluid must go. Dispose of waste according to your local environmental protocols.

3. The Dilution Solution

Rinse immediately.

If your system is aqueous, use Deionized (DI) water. If non-aqueous, use a high-purity solvent compatible with your chemistry.

The goal here is not just "clean." It is to return the surface to a neutral state before anything has a chance to adhere. Three rinses is the standard. It is the redundancy that guarantees success.

4. The Separation of Powers

Remove the electrodes.

The working, reference, and counter electrodes are distinct entities with different needs. They should be cleaned and stored separately. Leaving them in the cell increases the risk of mechanical breakage—clinking glass against metal is a sound no chemist wants to hear.

5. The Invisible Finish

Dry with intention.

Do not use a paper towel. Do not use compressed air from the wall (which often contains oil and moisture from the compressor).

Use a gentle stream of high-purity nitrogen or argon gas. This eliminates water spots, which are essentially concentrated deposits of impurities. An inert gas dry ensures that the only thing left in your cell is the quartz itself.

The System View

We can summarize the workflow as follows. If you skip a step, you introduce noise into your next dataset.

| Phase | Action | The "Why" (Engineering Logic) |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | De-energize System | Prevents arcing and thermal shock. |

| Removal | Drain Immediately | Prevents chemical etching and crystallization. |

| Reset | Multi-stage Rinse | Dilution reduces contaminant concentration to near zero. |

| Care | Isolate Electrodes | Prevents mechanical impact damage. |

| Storage | Inert Gas Dry | Eliminates atmospheric contaminants and water spots. |

The Compound Interest of Care

There is a psychological concept called "compound interest" that applies to habits as much as money.

If you clean your cell imperfectly today, the residue might be undetectable. But if you do it imperfectly ten times, the background noise in your voltammetry increases. The baseline shifts. Suddenly, your results aren't reproducible, and you don't know why.

You end up blaming the chemicals, or the sample, or the potentiostat. But the culprit was the "good enough" cleaning habit formed three months ago.

At KINTEK, we understand that great science is built on reliable tools. We engineer our lab equipment to the highest standards, but even the best equipment relies on the discipline of the user.

Whether you need high-purity replacement solvents, new reference electrodes, or a custom all-quartz cell designed for specific geometries, we view our role as the guardians of your variables. We provide the equipment; you provide the discipline.

Together, we ensure that when you look at your data, you are seeing the truth, not the residue.

Visual Guide

Related Products

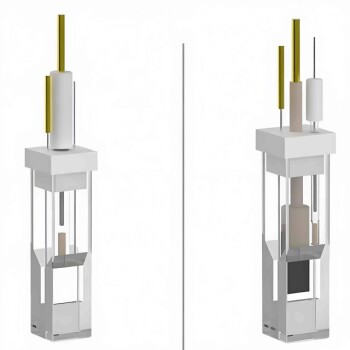

- Quartz Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Electrochemical Experiments

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

Related Articles

- The Architecture of Invisibility: Deconstructing the "All-Quartz" Cell

- The Architecture of Precision: Why the Invisible Details Define Electrochemical Success

- The Architecture of Precision: Mastering the Five-Port Water Bath Electrolytic Cell

- Understanding Quartz Electrolytic Cells: Applications, Mechanisms, and Advantages

- The Silent Dialogue: Mastering Control in Electrolytic Cells