In surgery, a sterile field is not a luxury; it is the baseline requirement for success. If the environment is compromised, the skill of the surgeon becomes irrelevant.

Laboratory science operates on the same brutal logic.

We spend weeks calculating molarities and calibrating potentiostats. We obsess over the reaction inside the vessel. But we rarely pause to consider the vessel itself. This is a psychological blind spot. We look through the window, forgetting that the window is a material object with its own physics and chemistry.

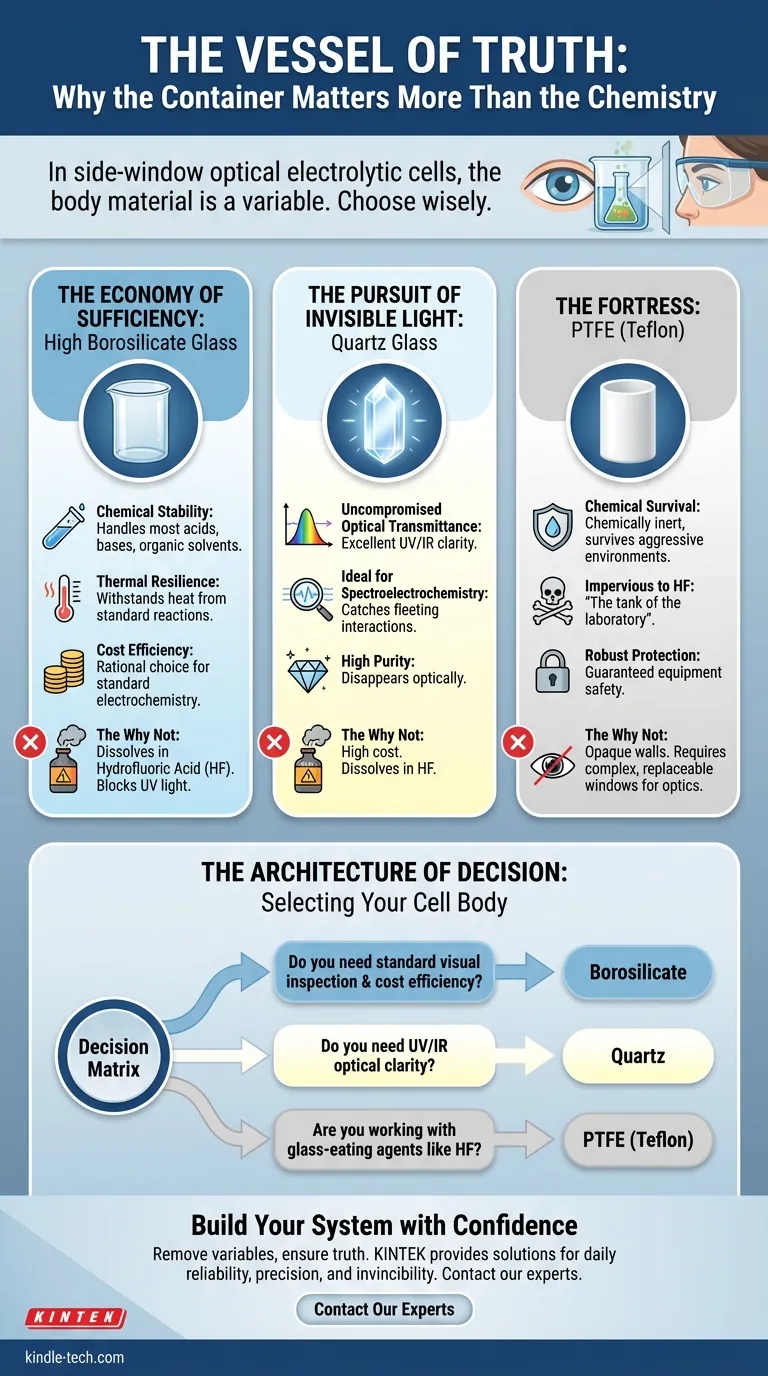

In side-window optical electrolytic cells, the body material is not merely a container. It is a variable.

Choose the wrong one, and you introduce noise. Choose the worst one, and you destroy your equipment.

Here is how to think about the architecture of your experiment, moving from the standard to the specialized.

The Economy of Sufficiency: High Borosilicate Glass

There is a tendency in engineering to over-optimize. We want the best specifications, regardless of need. But in most scenarios, "good enough" is not mediocrity—it is efficiency.

High borosilicate glass is the electrochemical equivalent of the concrete foundation. It is boring, ubiquitous, and for 80% of applications, exactly what you need.

It offers a robust balance:

- Chemical Stability: It handles most acids, bases, and organic solvents without complaint.

- Thermal Resilience: It withstands the heat generated by standard reactions.

- Cost Efficiency: It respects your budget.

If your experiment is standard electrochemistry, borosilicate is the rational choice. It allows you to see the reaction without paying for optical properties you do not need.

The Pursuit of Invisible Light: Quartz Glass

Sometimes, however, the data you need isn't chemical change—it is light.

Spectroelectrochemistry is the art of catching fleeting interactions. When you need to measure wavelengths in the ultraviolet (UV) or infrared (IR) spectrum, borosilicate glass becomes a wall. It blocks the very signal you are trying to detect.

This is where Quartz Glass becomes non-negotiable.

Quartz is defined by its purity. It offers uncompromised optical transmittance across the entire spectrum. It disappears, optically speaking, leaving you with nothing but the data.

The trade-off is cost. Quartz is difficult to manufacture and expensive to buy. But just as you wouldn't put cheap tires on a Formula 1 car, you cannot use standard glass when UV transparency is the mission.

The Fortress: PTFE (Teflon)

There is a specific category of failure in the lab that comes from underestimating aggression.

Some chemical environments are not just reactive; they are destructive. The most notorious villain is Hydrofluoric Acid (HF).

HF has a unique appetite for silica. It will eat through borosilicate and quartz with terrifying speed. Putting HF in a glass cell is not an experiment; it is a guaranteed equipment failure.

For these aggressive environments, we turn to Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE).

PTFE is the tank of the laboratory. It is chemically inert to almost everything. It survives where glass dissolves.

The Price of Protection: The cost of using PTFE is visibility. It is opaque. You cannot see through the walls of the fortress. To perform optical measurements, a PTFE cell body must be fitted with separate, replaceable windows (usually quartz).

It is a complex assembly for a complex problem, but it is the only way to remain safe when the chemistry turns hostile.

The Architecture of Decision

Selecting a cell body is a study in trade-offs. There is no "perfect" material, only the material that aligns with your constraints.

The decision matrix is simple, yet unforgiving:

- The Optical Trade-off: Do you need UV clarity (Quartz), or is visual inspection enough (Borosilicate)?

- The Chemical Trade-off: Are you working with standard electrolytes, or glass-eating agents like HF (PTFE)?

- The Financial Trade-off: Are you paying for performance you don't use?

Summary of Materials

| Material | The "Why" | The "Why Not" |

|---|---|---|

| High Borosilicate Glass | The rational default. Good stability, low cost. | Dissolves in Hydrofluoric Acid (HF). Blocks UV light. |

| Quartz Glass | Perfect optical clarity for UV/IR measurements. | High cost. Dissolves in HF. |

| PTFE (Teflon) | Total chemical survival. Impervious to HF. | Opaque walls. Requires complex assembly for optics. |

Build Your System

Good science is about removing variables until only the truth remains. The wrong cell material introduces a variable that can skew your data or halt your lab entirely.

At KINTEK, we understand that you aren't just buying a cell; you are buying the assurance that your equipment will not be the reason your experiment fails. Whether you need the daily reliability of borosilicate, the precision of quartz, or the invincibility of PTFE, we have the solution.

Let’s ensure your vessel is as robust as your hypothesis.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Quartz Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Electrochemical Experiments

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

Related Articles

- Understanding Quartz Electrolytic Cells: Applications, Mechanisms, and Advantages

- The Glass Heart of the Experiment: Precision Through Systematic Care

- The Art of the Empty Vessel: Preparing Quartz Electrolytic Cells for Absolute Precision

- The Geometry of Control: Why Millimeters Matter in Electrochemistry

- The Architecture of Invisibility: Deconstructing the "All-Quartz" Cell