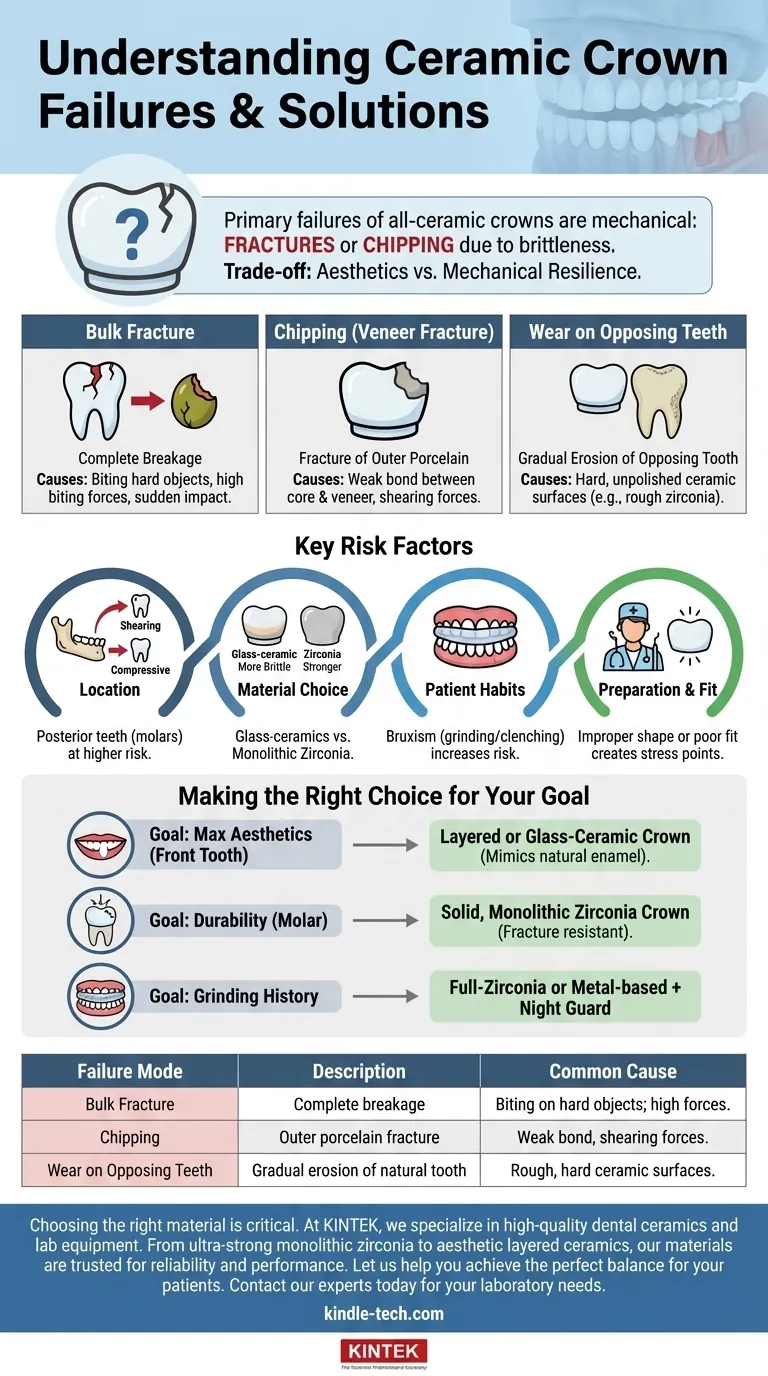

The primary failures of all-ceramic crowns are mechanical, most often involving fractures or chipping due to their brittle nature. While they offer superior aesthetics and biocompatibility, their main drawback compared to metal-based options is a lower tolerance for intense biting forces, which can lead to cracks in the material or wear on the opposing natural teeth.

The decision to use a ceramic crown involves a fundamental trade-off between aesthetics and mechanical resilience. Understanding the specific type of ceramic and its intended location in the mouth is the most critical factor in predicting its long-term success.

The Primary Modes of Ceramic Crown Failure

While modern ceramics are incredibly strong, they are not infallible. Their failures are almost always related to their inherent material properties and the forces they are subjected to.

Bulk Fracture

The most significant failure is a complete fracture of the crown itself. Ceramics are very strong under compression but can be brittle under tension or sudden, sharp impact.

This can happen when biting down on something unexpectedly hard, like an olive pit or a popcorn kernel. The force concentrates on a small point, creating a crack that propagates through the material.

Chipping (Veneer Fracture)

Many aesthetic crowns consist of a strong ceramic core (like zirconia) covered by a weaker, more translucent layer of porcelain. This layering achieves a life-like appearance.

However, the bond between these two layers can be a weak point. The outer porcelain can chip or shear off, exposing the duller core underneath. While the crown is still functional, its aesthetic value is compromised.

Wear on Opposing Teeth

High-strength ceramics, particularly some types of zirconia, are harder than natural tooth enamel.

If the crown's biting surface is not perfectly polished and smooth, it can act like fine sandpaper, gradually wearing down the opposing natural tooth over time. This is what is meant when it is said they can "weaken" adjacent teeth.

Understanding the Key Risk Factors

A crown's success is not determined by the material alone. Several clinical and patient-specific factors dramatically influence the risk of failure.

Location in the Mouth

A crown on a front tooth experiences shearing forces, while a molar crown endures immense compressive forces from chewing. Posterior teeth (molars) are at a much higher risk of fracture due to these high loads.

Choice of Ceramic Material

"All-ceramic" is a broad category. Materials like glass-ceramics are highly aesthetic and bond well to the tooth but are more brittle. Monolithic zirconia is far stronger and fracture-resistant but can be less translucent.

Patient Habits

Patients who clench or grind their teeth (bruxism) place extreme and prolonged stress on their restorations. This parafunctional habit dramatically increases the likelihood of fracture, chipping, or wear for any type of crown.

Preparation and Fit

The success of a crown begins with the dentist. An improperly shaped tooth preparation or a poorly fitting crown creates internal stress points. Over time, these stress concentrations can easily lead to a fracture.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Selecting the right material is a collaborative decision between you and your dentist, based on balancing aesthetics, function, and risk.

- If your primary focus is maximum aesthetics for a front tooth: A layered or glass-ceramic crown is often the best choice, as its translucency mimics natural enamel perfectly.

- If your primary focus is durability for a molar: A solid, monolithic zirconia crown is the superior option, prioritizing fracture resistance over the ultimate aesthetic result.

- If you have a history of grinding or clenching: A full-zirconia or even a metal-based crown is often recommended, and a protective night guard is essential to prevent damage.

Ultimately, a well-designed and properly placed ceramic crown can provide a beautiful, durable, and long-lasting result when its limitations are respected.

Summary Table:

| Failure Mode | Description | Common Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Fracture | Complete breakage of the crown. | Biting on hard objects; high biting forces. |

| Chipping | Fracture of the outer porcelain layer. | Weak bond between core and veneer; shearing forces. |

| Wear on Opposing Teeth | Gradual erosion of the natural tooth opposite the crown. | Hard, unpolished ceramic surfaces (e.g., some zirconia). |

Choosing the right ceramic material is critical for a long-lasting, beautiful restoration.

At KINTEK, we specialize in providing high-quality dental ceramics and lab equipment for creating precise, durable crowns. Whether you need ultra-strong monolithic zirconia for posterior teeth or highly aesthetic layered ceramics for anterior restorations, our materials are trusted by dental professionals for their reliability and performance.

Let us help you achieve the perfect balance of aesthetics and function for your patients. Contact our experts today to discuss your specific laboratory needs and find the ideal solution.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Dental Porcelain Zirconia Sintering Ceramic Furnace Chairside with Transformer

- Vacuum Dental Porcelain Sintering Furnace

- High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory Debinding and Pre Sintering

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Vertical Laboratory Tube Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is a dental oven? The Precision Furnace for Creating Strong, Aesthetic Dental Restorations

- What is the sintering time for zirconia? A Guide to Precise Firing for Optimal Results

- What is the sintering temperature of zirconium? A Guide to the 1400°C-1600°C Range for Dental Labs

- What makes zirconia translucent? The Science Behind Modern Dental Aesthetics

- What is the temperature of sintering zirconia? Mastering the Protocol for Perfect Dental Restorations