The three essential components of an electrolytic cell are the electrolyte and two specific electrodes: the cathode and the anode. These components work in unison to facilitate non-spontaneous chemical reactions when connected to an external voltage source.

An electrolytic cell acts as a vessel for converting electrical energy into chemical energy. By applying external voltage to two distinct electrodes submerged in a conductive medium, the system forces reduction and oxidation reactions that would not occur naturally.

The Role of the Electrodes

The electrodes are the solid conductors that introduce electricity into the cell. They are the sites where the critical chemical changes—known as redox events—take place.

The Cathode (The Negative Electrode)

In an electrolytic setup, the cathode is the electrode connected to the negative terminal of the power source. Because it is negatively charged, it attracts positively charged ions (cations) from the solution.

This is the site of reduction, meaning electrons are gained here. When positive ions touch the cathode, they accept electrons and are reduced to a neutral state (e.g., sodium ions becoming sodium metal).

The Anode (The Positive Electrode)

The anode is connected to the positive terminal of the external power source. It attracts negatively charged ions (anions) floating in the electrolyte.

This is the site of oxidation, where electrons are lost. Anions travel to the anode to release their electrons, which then travel back up the wire to the power source, completing the external circuit.

The Function of the Electrolyte

The electrolyte is the chemical medium that connects the two electrodes inside the cell. Without it, the circuit would be broken, and no reaction could occur.

A Medium for Ion Movement

The electrolyte contains dissolved ions that are free to move. This mobility is crucial because it allows electric charge to flow through the liquid (or molten) phase of the cell.

While electrons flow through the external wires, ions flow through the electrolyte to balance the charge.

Forms of Electrolytes

Typically, the electrolyte is a solution, such as salt dissolved in water or other solvents. However, it can also be a molten salt, like liquid sodium chloride.

Molten salts are often used when water would interfere with the desired reaction, such as in the industrial production of pure sodium or aluminum.

Understanding the Constraints and Trade-offs

While electrolytic cells are powerful tools for chemical synthesis and purification, they function differently than batteries (galvanic cells). Understanding these differences is vital for proper application.

Dependency on External Power

Unlike a battery, which produces electricity, an electrolytic cell consumes electricity. It requires a constant external voltage source to drive the reaction.

If the external voltage is removed, the reaction stops immediately.

Electrode Stability

A common pitfall is the degradation of the anode. Because the anode is the site of oxidation, the electrode material itself can sometimes oxidize and dissolve into the solution.

If the goal is to produce a gas (like chlorine) rather than dissolve the electrode, you must use an inert electrode (like carbon or platinum) that resists corrosion.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

When designing or analyzing an electrolytic system, your choice of components dictates the efficiency and outcome of the reaction.

- If your primary focus is refining metals: Ensure your electrolyte is a molten salt rather than an aqueous solution to prevent water from reacting preferentially.

- If your primary focus is durability: Select inert electrodes (such as platinum or graphite) for the anode to prevent it from disintegrating during the oxidation process.

The effectiveness of any electrolytic cell relies on the seamless interaction between a conductive electrolyte and two electrodes properly polarized to drive the specific redox reaction you require.

Summary Table:

| Component | Charge in Electrolytic Cell | Primary Function | Chemical Process |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cathode | Negative (-) | Attracts cations and supplies electrons | Reduction (Gain of electrons) |

| Anode | Positive (+) | Attracts anions and receives electrons | Oxidation (Loss of electrons) |

| Electrolyte | Neutral (Medium) | Facilitates ion movement and completes the circuit | Ion Transport |

Maximize Your Laboratory Precision with KINTEK

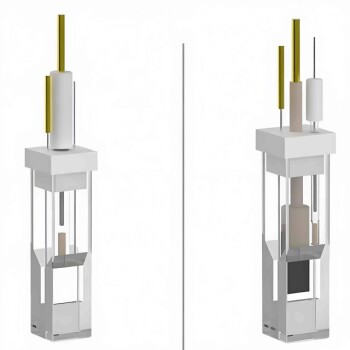

High-performance electrochemistry requires more than just knowledge—it demands superior hardware. KINTEK specializes in advanced laboratory equipment, providing researchers and industrial professionals with top-tier electrolytic cells, high-purity electrodes, and durable consumables designed to withstand rigorous redox reactions.

Whether you are refining metals, exploring battery research, or performing complex chemical synthesis, our comprehensive portfolio—including high-temperature furnaces, hydraulic presses, and specialized ceramics—ensures your lab operates at peak efficiency.

Ready to upgrade your research capabilities? Contact KINTEK today for expert guidance and tailored solutions!

Related Products

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Quartz Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Electrochemical Experiments

- H-Type Double-Layer Optical Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Water Bath

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

People Also Ask

- What general precaution should be taken when handling the electrolytic cell? Ensure Safe and Accurate Lab Results

- How can contamination be avoided during experiments with the five-port water bath electrolytic cell? Master the 3-Pillar Protocol

- How should the body of an electrolytic cell be maintained for longevity? Extend Your Equipment's Lifespan

- What are the proper storage procedures for the multifunctional electrolytic cell? Protect Your Investment and Ensure Data Accuracy

- How should the five-port water bath electrolytic cell be cleaned for maintenance? A Step-by-Step Guide to Reliable Results