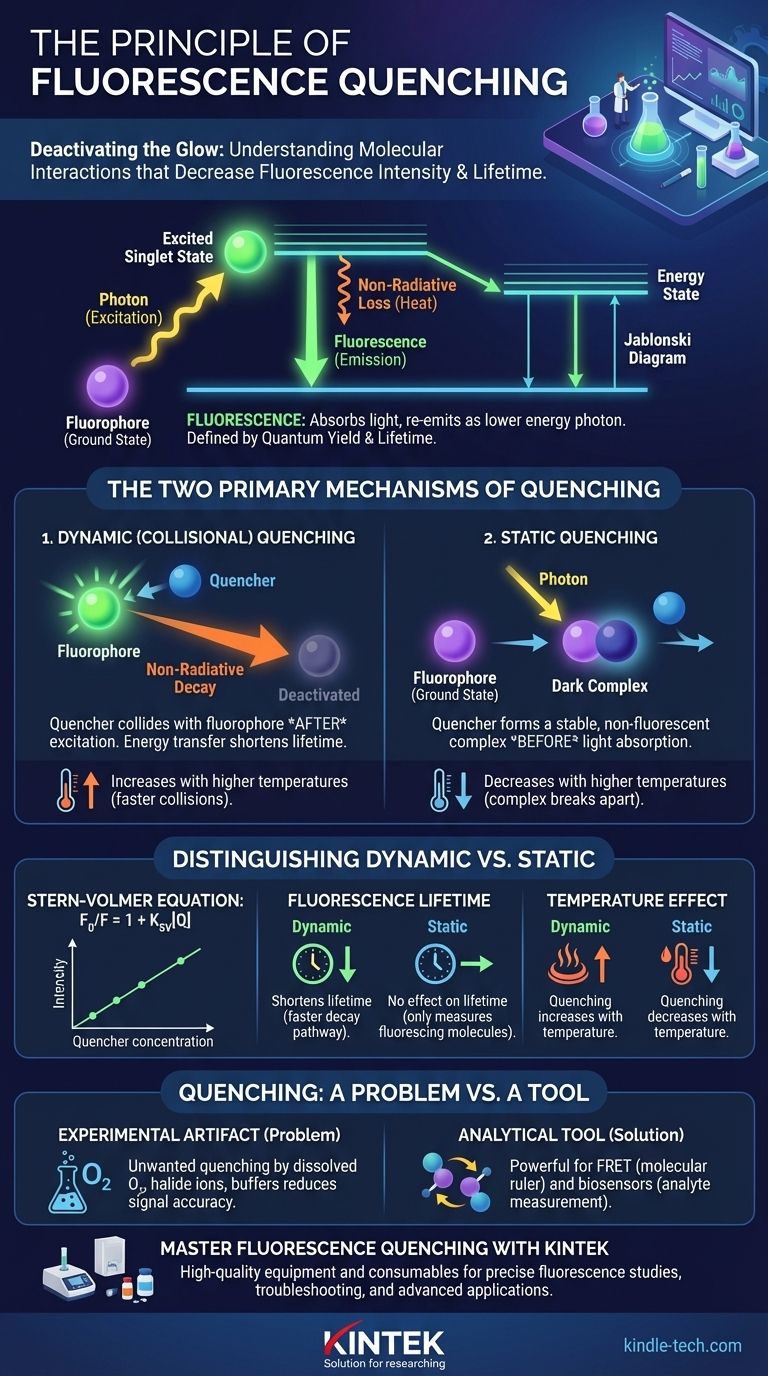

In essence, the quenching effect is any process that decreases the intensity and/or lifetime of fluorescence from a given substance. This occurs when an excited fluorophore—a molecule that can absorb and re-emit light—is deactivated by an interaction with another molecule, known as a quencher. Instead of releasing its absorbed energy as a photon of light, the fluorophore returns to its ground state through a non-radiative pathway, effectively dimming or extinguishing its glow.

The core principle is that quenching is not simply about dimming a signal; it's a specific molecular interaction. Understanding whether this interaction happens before or after light absorption is the key to distinguishing its primary types and deciding if quenching is an experimental problem to be fixed or a powerful analytical tool to be exploited.

The Foundation: How Fluorescence Works

To grasp quenching, you must first understand its opposite: fluorescence. This phenomenon is a multi-step process governed by the energy states of a molecule.

The Jablonski Diagram in Brief

A simplified Jablonski diagram helps visualize the process. First, a fluorophore absorbs a photon of light, promoting an electron to a higher energy, excited singlet state.

This excited state is unstable. The molecule quickly loses a small amount of energy as heat or vibration before emitting the remaining energy as a lower-energy (longer wavelength) photon, which we see as fluorescence.

Fluorescence Lifetime and Quantum Yield

Two properties define a fluorophore's emission. Quantum yield is the efficiency of this process—the ratio of photons emitted to photons absorbed. Fluorescence lifetime is the average time the fluorophore spends in the excited state before returning to the ground state, typically on the order of nanoseconds. Quenching directly reduces both of these values.

The Two Primary Mechanisms of Quenching

The interaction between a fluorophore and a quencher can happen in two fundamentally different ways, which have distinct experimental signatures.

Dynamic (Collisional) Quenching

Dynamic quenching occurs when a quencher molecule collides with a fluorophore after it has already been excited by light. During this collision, energy is transferred from the fluorophore to the quencher.

This contact provides an external, non-radiative pathway for the excited fluorophore to return to its ground state. Because it depends on random collisions, this process is highly dependent on factors like temperature and viscosity that affect molecular diffusion.

Static Quenching

Static quenching happens when a quencher molecule forms a stable, non-fluorescent complex with a fluorophore before light absorption occurs. This ground-state complex is effectively "dark."

When this complex absorbs a photon, it immediately returns to the ground state without emitting any light. The observed decrease in fluorescence comes from the fact that a fraction of the fluorophores were already tied up and unable to fluoresce in the first place.

Distinguishing Dynamic vs. Static Quenching

For any experiment, determining the type of quenching is critical. Fortunately, they have different effects on the fluorophore's properties.

The Stern-Volmer Equation

The relationship between fluorescence intensity and quencher concentration is described by the Stern-Volmer equation: F₀/F = 1 + Kₛᵥ[Q].

Here, F₀ is the fluorescence intensity without a quencher, F is the intensity with a quencher, [Q] is the quencher's concentration, and Kₛᵥ is the Stern-Volmer quenching constant. A linear plot of F₀/F versus [Q] is indicative of a single quenching mechanism.

The Impact on Fluorescence Lifetime

This is the definitive test. Dynamic quenching shortens the measured fluorescence lifetime because it introduces a faster pathway for the excited fluorophore to return to the ground state.

Conversely, static quenching has no effect on the fluorescence lifetime. The fluorophores that are not part of the ground-state complex fluoresce normally, and the "quenched" molecules were never excited to begin with. The lifetime measurement only captures the signal from the molecules that are still able to fluoresce.

The Effect of Temperature

Temperature is another powerful diagnostic tool. Because dynamic quenching relies on collisions, its rate increases with higher temperatures, which cause molecules to move and diffuse faster.

Static quenching, however, relies on a stable complex. Higher temperatures often provide enough energy to break this complex apart, thus decreasing the amount of static quenching.

Quenching: A Problem vs. a Tool

Quenching is a double-edged sword in scientific research. Depending on the context, it can be a frustrating source of error or a highly precise measurement technique.

Quenching as an Experimental Artifact

Unwanted quenching is a common problem. Common culprits in biological samples include dissolved oxygen, halide ions (like Cl⁻ or I⁻), and certain buffer components. This can lead to a reduced signal-to-noise ratio and inaccurate measurements.

Quenching as an Analytical Tool

When controlled, quenching is incredibly powerful. Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) is a special type of quenching where energy is transferred between two different fluorophores, allowing researchers to measure molecular distances on a nanometer scale.

Furthermore, quenching-based biosensors are designed so that the presence of a specific analyte (like glucose or oxygen) quenches a fluorescent signal. The degree of quenching becomes a direct readout of the analyte's concentration.

Applying This Knowledge to Your Experiment

Your approach to quenching depends entirely on your experimental goal.

- If your primary focus is maximizing a fluorescent signal: Scrutinize your solutions for common quenchers (e.g., acrylamide, iodide, dissolved O₂) and consider degassing samples or using different buffers.

- If your primary focus is measuring analyte concentration: Design a system where your target analyte is the quencher, allowing you to calculate its concentration by measuring the predictable drop in fluorescence.

- If your primary focus is studying molecular interactions: Employ controlled quenching techniques like FRET, where the quenching of a "donor" fluorophore by an "acceptor" provides a direct measure of their proximity.

By understanding the principles of quenching, you transform it from a potential obstacle into a precise instrument for molecular investigation.

Summary Table:

| Quenching Type | Mechanism | Effect on Lifetime | Temperature Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic (Collisional) | Quencher collides with excited fluorophore | Shortens lifetime | Increases with temperature |

| Static | Forms non-fluorescent complex before excitation | No effect on lifetime | Decreases with temperature |

Ready to master fluorescence quenching in your lab? KINTEK specializes in high-quality lab equipment and consumables, including fluorometers, quenchers, and reagents essential for precise fluorescence studies. Whether you're troubleshooting unwanted quenching or developing advanced biosensors, our solutions ensure accurate, reliable results. Contact our experts today to optimize your fluorescence experiments!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Integrated Manual Heated Plates for Lab Use

- Manual Lab Heat Press

- 30T 40T Split Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory Hot Press

- Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press for XRF KBR FTIR Lab Applications

- 24T 30T 60T Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory Hot Press

People Also Ask

- What are the technical requirements for vacuum chambers in desalination? Boost Efficiency with Graphene Technology

- What are the options for industrial heating? Fuel vs. Electric Systems Explained

- Why is a drying oven used for low-temperature treatment of Ti/Al2O3? Ensure Powder Purity and Flowability

- Is XRF testing Qualitative or quantitative? Unlocking Its Dual Role in Elemental Analysis

- What is the importance of a laboratory electric constant temperature drying oven? Ensure Accurate Biomass Analysis

- What is the maximum thickness of sputtering? Overcoming Stress and Adhesion Limits

- What is the role of a magnetic stirrer in npAu catalyst preparation? Ensure Uniform Coating and Deep Diffusion

- Why does the high-temperature sealing process for inorganic-carbonate dual-phase membranes require a heating furnace with precise temperature control? Ensure Leak-Free Bonds.