Crucially, annealing is not defined by cooling to a specific temperature, but by the controlled rate of cooling. For a full anneal, the material is cooled as slowly as possible, typically by leaving it in the furnace after it has been turned off and allowing it to cool to ambient temperature over many hours. The goal is to let the material's internal structure fully relax and re-form.

The single most important factor in annealing is not a target temperature, but the extremely slow cooling rate. This deliberate process is what allows the material's microstructure to reset, eliminating internal stresses and maximizing its softness and ductility.

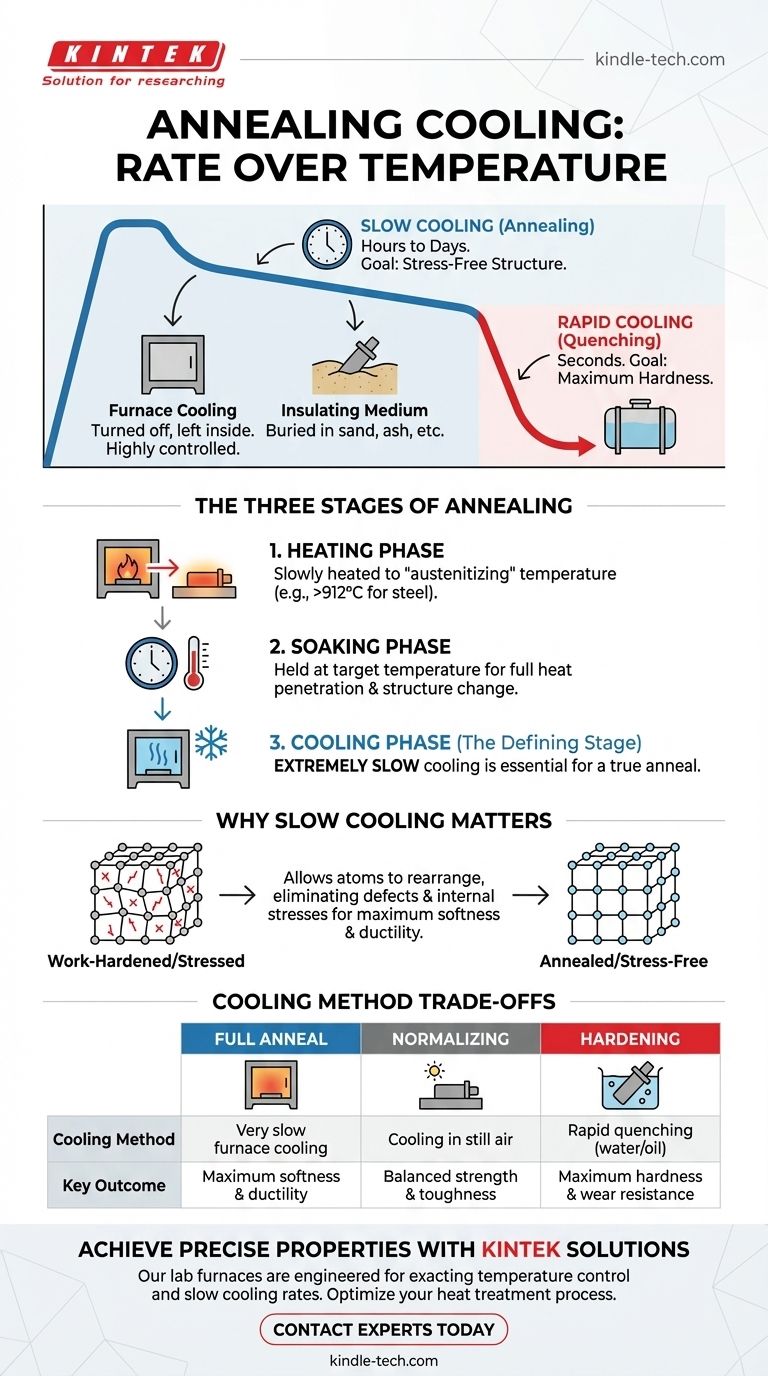

The Three Stages of Annealing

To understand the cooling process, you must first understand its place within the overall annealing cycle. Annealing is a three-part process designed to alter the physical and sometimes chemical properties of a material.

Stage 1: The Heating Phase

First, the material is slowly and uniformly heated to a specific "austenitizing" temperature. This temperature is critical and varies by material, but for steel, it's typically above its upper critical temperature (around 912 °C or 1674 °F) where its crystal structure changes.

Stage 2: The Soaking Phase

Once at the target temperature, the material is "soaked"—held at that temperature for a specific duration. This allows the heat to fully penetrate the entire workpiece, ensuring a complete and uniform change in its internal crystal structure.

Stage 3: The Cooling Phase

This is the defining stage. After soaking, the material must be cooled in a highly controlled manner. For a true or "full" anneal, this cooling must be extremely slow.

Why Slow Cooling is the Defining Factor

The rate of cooling directly manipulates the final microstructure of the material, which in turn dictates its mechanical properties like hardness and ductility.

The Goal: A Stress-Free Structure

Work-hardening a metal through processes like bending or hammering creates a large number of defects (dislocations) in its crystal lattice, making it hard and brittle. Slow cooling allows the atoms to migrate and rearrange themselves into a near-perfect, low-stress crystal structure, effectively erasing the effects of work hardening.

How "Slow" is Achieved in Practice

The term "slow" almost always means furnace cooling. The heating elements of the furnace are turned off, and the part is left inside. The furnace's own thermal mass and insulation prevent rapid heat loss, forcing a gradual temperature drop over 8 to 20+ hours, until it reaches room temperature.

For some applications or materials, the part might be removed from the furnace and immediately buried in an insulating medium like sand, ash, or vermiculite. This also slows heat loss significantly compared to cooling in open air.

Understanding the Trade-offs: Annealing vs. Other Treatments

The cooling rate is the primary variable that distinguishes annealing from other common heat treatments.

Annealing vs. Normalizing

Normalizing also involves heating to a similar temperature, but the cooling is done by removing the part from the furnace and letting it cool in still air. This is faster than furnace cooling but slower than quenching. The result is a material that is stronger and harder than an annealed part but more ductile than a hardened one.

Annealing vs. Hardening (Quenching)

Hardening seeks the opposite effect of annealing. After soaking, the material is cooled as rapidly as possible by quenching it in a medium like water, oil, or brine. This rapid cooling traps the crystal structure in a hard, brittle state (martensite in steels). This maximizes hardness at the expense of ductility.

The Cost of an Anneal

The main trade-off of a full anneal is time and cost. Occupying a furnace for many hours during a slow cool-down cycle is energy-intensive and reduces production throughput. For this reason, normalizing is often chosen when maximum softness is not strictly required.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Your choice of cooling method should be dictated entirely by the final properties you need from the material.

- If your primary focus is maximum softness, ductility, and machinability: A full anneal with a slow furnace cool is the correct process.

- If your primary focus is refining grain structure and achieving a good balance of strength and toughness: Normalizing by cooling in still air is a more efficient choice.

- If your primary focus is achieving maximum hardness and wear resistance: You must use a rapid cooling method like quenching, followed by a secondary tempering process to reduce brittleness.

Ultimately, understanding that the cooling rate directly controls the material's final properties is the key to mastering any heat treatment process.

Summary Table:

| Heat Treatment | Cooling Method | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Full Anneal | Very slow furnace cooling | Maximum softness & ductility |

| Normalizing | Cooling in still air | Balanced strength & toughness |

| Hardening | Rapid quenching (water/oil) | Maximum hardness & wear resistance |

Achieve precise material properties with KINTEK's annealing solutions.

Our lab furnaces are engineered for the exacting temperature control and slow cooling rates required for successful annealing processes. Whether you're working to maximize softness for machining or need to refine grain structure, KINTEK provides the reliable equipment and expert support to meet your laboratory's specific material science goals.

Ready to optimize your heat treatment process? Contact our experts today to discuss how KINTEK's specialized lab equipment can enhance your research and development.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vertical Laboratory Tube Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace and Levitation Induction Melting Furnace

- 1700℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace Bottom Lifting Muffle Furnace

- 1800℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

People Also Ask

- How do you clean a tubular furnace tube? A Step-by-Step Guide to Safe and Effective Maintenance

- What is the temperature of a quartz tube furnace? Master the Limits for Safe, High-Temp Operation

- How do you clean a quartz tube furnace? Prevent Contamination & Extend Tube Lifespan

- What is the process of annealing tubes? Achieve Optimal Softness and Ductility for Your Tubing

- What is the difference between upflow and horizontal furnace? Find the Perfect Fit for Your Home's Layout