The Illusion of the Black Box

In laboratory science, we often treat equipment as passive vessels. We pour, we mix, we measure.

But in electrochemistry, the vessel is not passive. It is an active participant in the data.

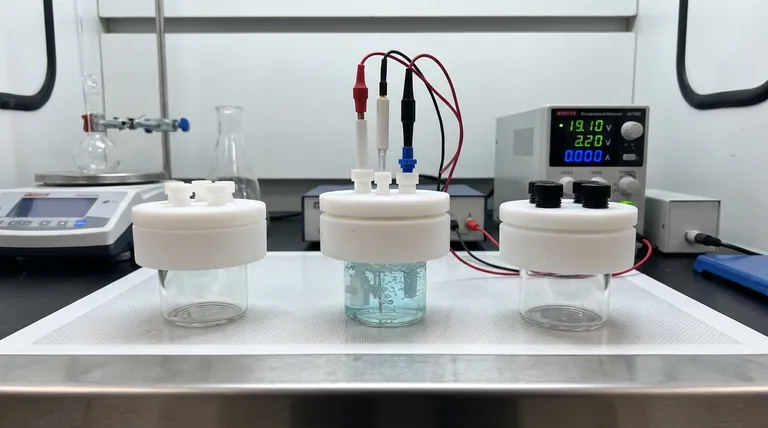

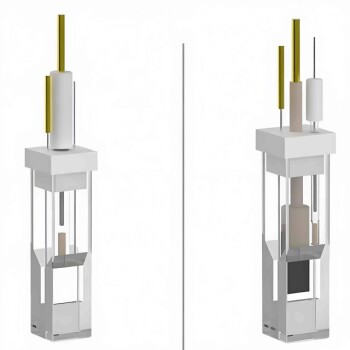

This is especially true for the super-sealed electrolytic cell. It represents a closed system—a "black box" where the variables are strictly defined by what you put in and how you seal it.

The difference between a breakthrough and a failed experiment often comes down to a bubble the size of a pinhead, or a connection that is 1% loose.

Success isn't found in the complexity of your hypothesis. It is found in the discipline of your setup.

Here is the engineering philosophy behind mastering the sealed cell.

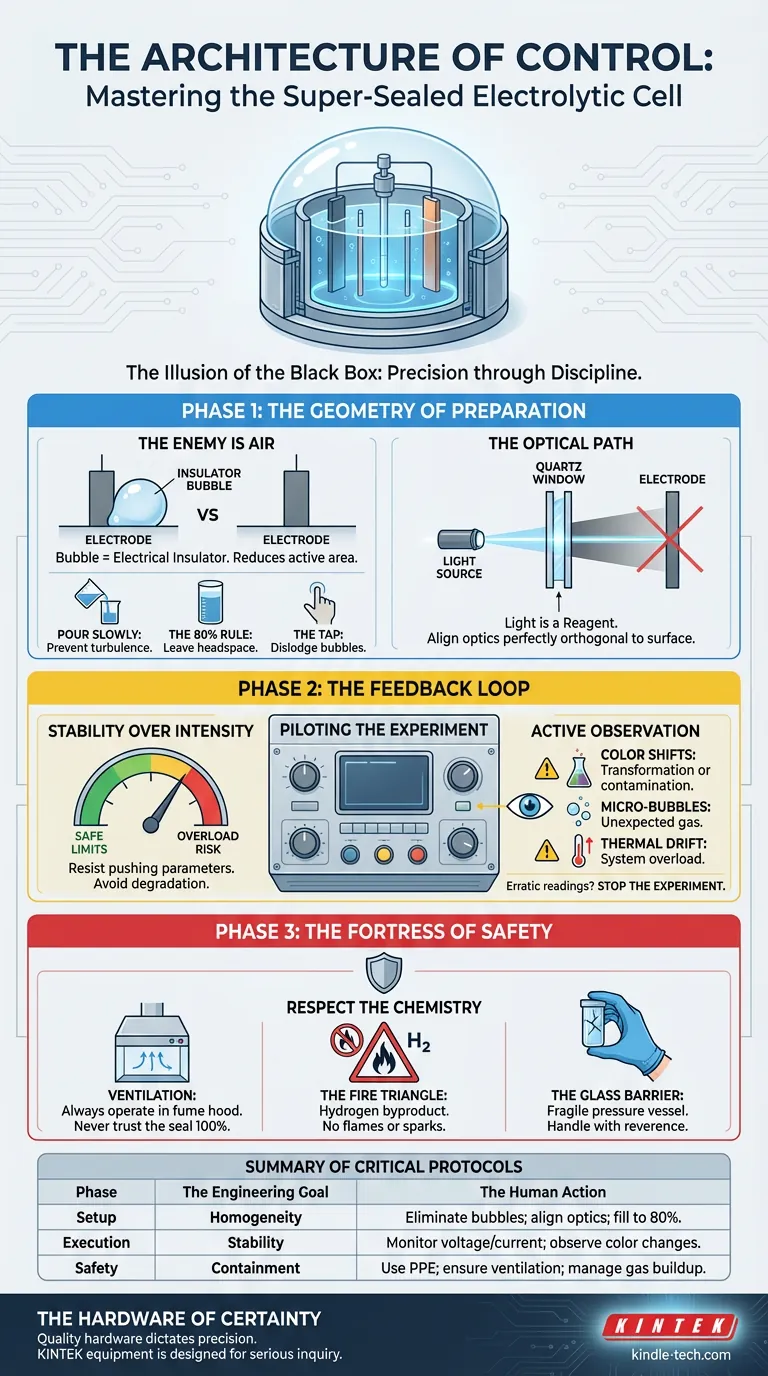

Phase 1: The Geometry of Preparation

You cannot fix a poor setup with good data analysis. The error is baked into the physical reality of the experiment before you even turn on the power.

The preparation phase is about geometry and fluid dynamics.

The Enemy is Air When filling the cell, your primary adversary is the air bubble. A bubble on an electrode surface is not just an annoyance; it is an electrical insulator. It effectively reduces the active surface area, skewing your current density calculations.

- Pour slowly: Introduce the electrolyte gently to prevent turbulence.

- The 80% Rule: Never fill the cell to the brim. Leave a headspace (fill to ~80%) to accommodate gas evolution and prevent splashing.

- The Tap: If bubbles adhere to the walls or electrodes, a gentle mechanical tap is usually sufficient to dislodge them.

The Optical Path For photoelectrochemical experiments, light is a reagent. Its delivery must be precise.

If your light source is misaligned with the quartz window, you create a gradient of intensity across the electrode. You are measuring the shadow, not the reaction. Ensure the optical path is perfectly orthogonal to the electrode surface.

Phase 2: The Feedback Loop

Once the experiment begins, you are no longer a builder; you are a pilot.

You are managing energy inputs (voltage/current) and monitoring outputs.

Stability Over Intensity There is a temptation to push parameters to their limits to see "what happens." Resist this.

Set your voltage and current within the known safe operating limits of the cell. Prolonged overload doesn't just risk the data; it degrades the electrode material, permanently altering the baseline for future experiments.

Active Observation Data loggers tell you what happened mathematically. Your eyes tell you what is happening physically.

Watch for the subtle signals:

- Color Shifts: A change in electrolyte hue indicates chemical transformation—or contamination.

- Micro-Bubbles: Unexpected gas generation on the counter electrode.

- Thermal Drift: Is the cell getting warm?

If the instrument readings become erratic, do not hope they will stabilize. Stop the experiment. An erratic reading is the system screaming that the feedback loop is broken.

Phase 3: The Fortress of Safety

A super-sealed cell is a pressure vessel in disguise.

It is designed to contain reactions that produce hazardous gases like hydrogen or chlorine. The seal protects the lab from the reaction, but it also traps the energy inside.

Respect the Chemistry

- Ventilation: Even with a sealed cell, never trust the seal 100%. Always operate in a well-ventilated fume hood.

- The Fire Triangle: Hydrogen is a common byproduct of electrolysis. Remove all open flames and potential spark sources from the vicinity.

- The Glass Barrier: The cell is likely glass. It is chemically resistant but mechanically fragile. Handle it with the reverence due to a fragile containment unit.

Summary of Critical Protocols

| Phase | The Engineering Goal | The Human Action |

|---|---|---|

| Setup | Homogeneity | Eliminate bubbles; align optics; fill to 80%. |

| Execution | Stability | Monitor voltage/current; observe color changes. |

| Safety | Containment | Use PPE; ensure ventilation; manage gas buildup. |

The Hardware of Certainty

Atul Gawande famously noted that failure usually comes from two sources: ignorance (not knowing enough) or ineptitude (not applying what we know).

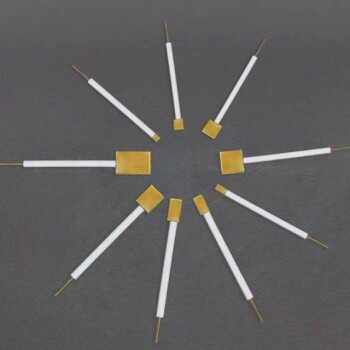

In electrochemistry, we remove the risk of ineptitude by establishing rigid protocols. But we remove the risk of variability by choosing the right hardware.

The quality of your electrolytic cell dictates the ceiling of your experimental precision. A poorly machined seal or an optically imperfect window introduces noise that no amount of procedure can fix.

KINTEK understands this engineer's romance with precision. We specialize in high-quality lab equipment and consumables designed to disappear into the background, letting your data stand out.

Whether you need perfectly sealed electrolytic cells or the safety gear to run them, our equipment is built for the rigors of serious inquiry.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- PTFE Electrolytic Cell Electrochemical Cell Corrosion-Resistant Sealed and Non-Sealed

Related Articles

- The Anchor of Truth: Why Physical Stability Defines Electrochemical Success

- The Vessel of Truth: Why the Container Matters More Than the Chemistry

- The Architecture of Precision: Mastering the Five-Port Water Bath Electrolytic Cell

- The Silent Dialogue: Mastering Control in Electrolytic Cells

- The Transparency Paradox: Mastering the Fragile Art of Electrolytic Cells