In the world of electrochemistry, success is often defined by what you manage to keep out.

You are building a microscopic universe. Inside the glass walls, ions move, oxidation occurs, and data flows. Outside, the chaos of the atmosphere—specifically oxygen and moisture—waits to ruin the experiment.

The vessel that separates these two worlds is the super-sealed electrolytic cell.

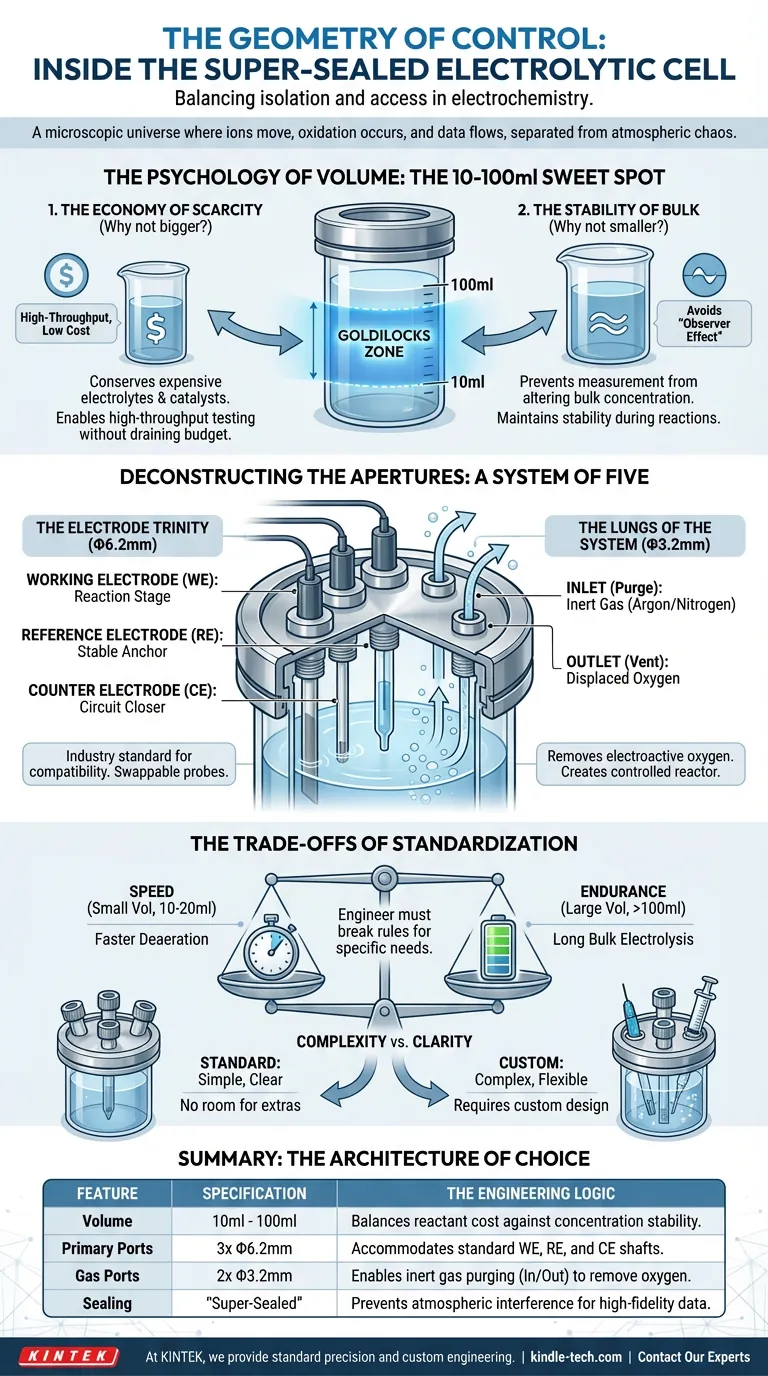

Its design is not accidental. The specific dimensions and configurations, typically a volume of 10ml to 100ml and a specific five-hole layout, represent a century of engineering compromises. They balance the physicist's need for isolation with the chemist’s need for access.

Here is the logic behind the glass.

The Psychology of Volume: The 10-100ml Sweet Spot

In laboratory science, volume is a proxy for two competing anxieties: the fear of waste and the fear of instability.

The standard super-sealed cell targets a specific range—10ml to 100ml—to resolve this tension.

1. The Economy of Scarcity (Why not bigger?)

Many advanced electrolytes, catalysts, and isotopes are prohibitively expensive. A 500ml or 1000ml cell requires a massive upfront investment in solvents and solutes.

By capping the standard at 100ml, the cell acts as a conservation device, allowing high-throughput testing without draining the budget.

2. The Stability of Bulk (Why not smaller?)

If you go too small (under 10ml), you risk the "Observer Effect."

As the reaction proceeds, the consumption of the analyte at the working electrode can significantly alter the bulk concentration of the tiny solution volume. The measurement itself changes the conditions of the experiment.

The 10-100ml range is the "Goldilocks" zone: large enough to maintain bulk concentration stability during typical cyclic voltammetry, yet small enough to be economical.

Deconstructing the Apertures: A System of Five

A sealed cell is useless if it is a fortress with no doors. You need to introduce inputs (electrodes) and manage the environment (gas).

The standard configuration uses a specific hierarchy of holes. It is an exercise in spatial efficiency.

The Electrode Trinity (Φ6.2mm)

Three distinct ports, drilled to a standard Φ6.2mm, dominate the cell cap. They are the interface for the three-electrode system:

- The Working Electrode (WE): The stage where the reaction happens.

- The Reference Electrode (RE): The stable anchor point for potential measurement.

- The Counter Electrode (CE): The circuit closer, balancing the current.

Why Φ6.2mm? It is the industry standard for electrode shaft diameters. It represents the "romance of compatibility"—the ability to swap probes between experiments without redesigning the vessel.

The Lungs of the System (Φ3.2mm)

The two smaller ports, sized at Φ3.2mm, are often overlooked, but they define the cell's "super-sealed" status.

Electrochemistry hates oxygen. Dissolved oxygen is an electroactive impurity that creates noise in the data. These two small ports allow the cell to "breathe" a controlled atmosphere:

- Inlet: For purging the solution with inert gas (Argon or Nitrogen).

- Outlet: For venting the displaced oxygen.

Without these, the cell is just a beaker. With them, it becomes a controlled reactor.

The Trade-offs of Standardization

Standardization is powerful, but it is not universal. The 5-port, 100ml design covers 90% of use cases, but the remaining 10% requires a deviation from the norm.

The engineer must know when to break the rules.

Volume vs. Time

- Speed: A smaller volume (10-20ml) deaerates faster. If you need to run quick scans on volatile solvents, go small.

- Endurance: For long-duration bulk electrolysis, the standard 100ml may still be too small. You may need a custom larger volume to prevent reactant depletion over hours of operation.

Complexity vs. Clarity

The standard cell has no room for extras. If your experiment requires a pH probe, a thermometer, or a syringe for standard addition, the 5-hole configuration fails. You are forced to choose: sacrifice a gas port (risking oxygen ingress) or commission a custom cell.

Summary: The Architecture of Choice

| Feature | Specification | The Engineering Logic |

|---|---|---|

| Volume | 10ml - 100ml | Balances reactant cost against concentration stability. |

| Primary Ports | 3x Φ6.2mm | Accommodates the standard WE, RE, and CE shafts. |

| Gas Ports | 2x Φ3.2mm | Enables inert gas purging (In/Out) to remove oxygen. |

| Sealing | "Super-Sealed" | Prevents atmospheric interference for high-fidelity data. |

Conclusion

The super-sealed electrolytic cell is more than a glass container; it is a tool for removing variables.

By standardizing the volume and apertures, it allows the researcher to focus entirely on the electrochemistry, trusting that the environment is controlled and the connections are secure.

However, when your research pushes the boundaries of the standard configuration—whether you need simultaneous pH monitoring or extended bulk electrolysis volumes—you need a partner who understands both the glass and the science.

At KINTEK, we provide the standard precision you expect and the custom engineering you require.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

- Double Layer Five-Port Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Quartz Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Electrochemical Experiments

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

Related Articles

- The Architecture of Precision: Mastering the Five-Port Water Bath Electrolytic Cell

- The Fragility of Precision: Mastering the Integrity of Five-Port Electrolytic Cells

- The Silent Variable: Engineering Reliability in Electrolytic Cells

- The Architecture of Precision: Why the Invisible Details Define Electrochemical Success

- The Art of the Sealed System: Mastering the Five-Port Electrolytic Cell