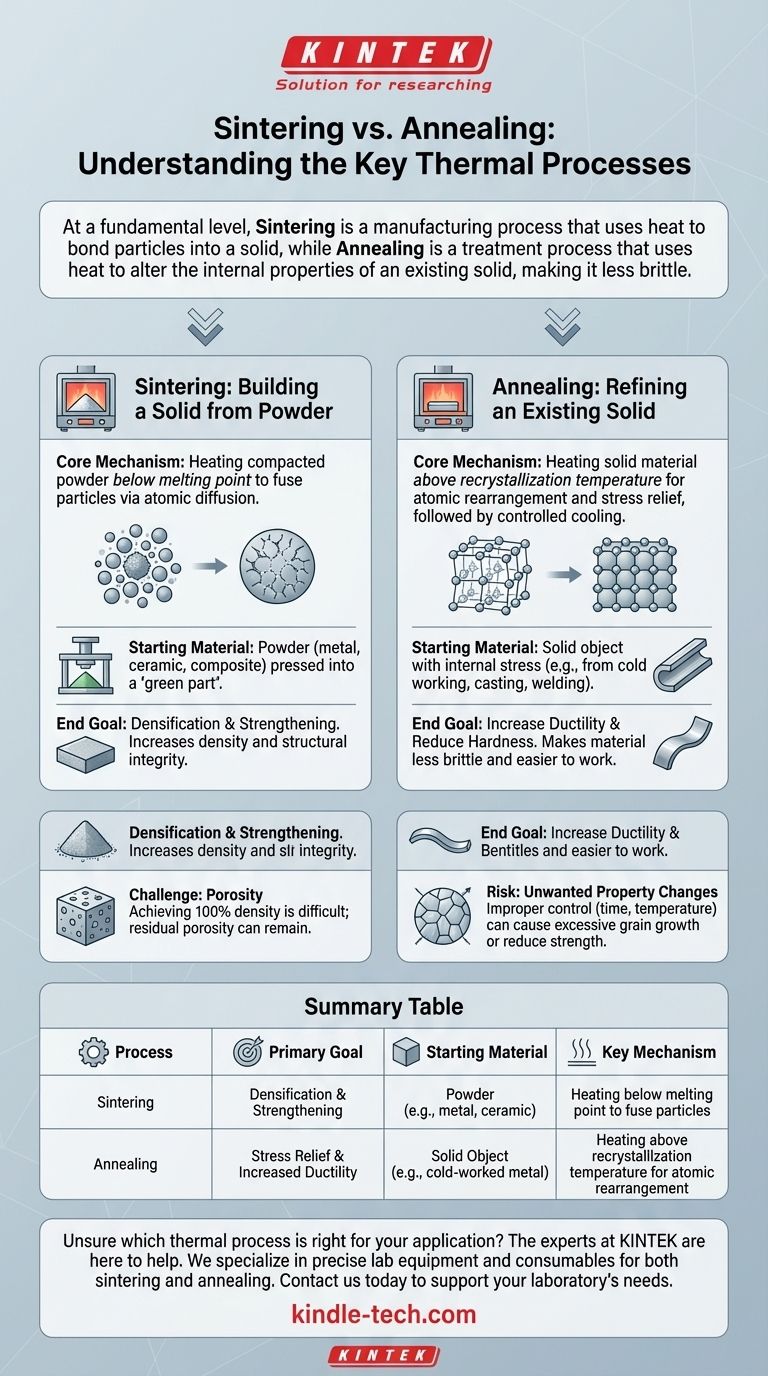

At a fundamental level, sintering is a manufacturing process that uses heat to bond particles together into a solid, dense object. In contrast, annealing is a treatment process that uses heat to alter the internal properties of an existing solid object, making it less brittle and more workable. Sintering creates the object; annealing refines it.

The essential distinction is one of intent: Sintering is a formative process used to construct a solid part from a powder, while Annealing is a corrective process used to relieve internal stress and improve the properties of an already-formed part.

Sintering: Building a Solid from Powder

Sintering is a cornerstone of powder metallurgy and ceramics manufacturing. It transforms a loose collection of particles into a coherent, solid mass with useful mechanical properties.

The Core Mechanism

The process involves heating a compacted powder to a high temperature, but crucially, below the material's melting point. At this temperature, the atoms at the contact points of the particles diffuse across the boundaries, fusing the individual particles into a single, solid piece.

The Starting Material

Sintering always begins with a powder. This could be a metal, ceramic, or composite material that has been pressed into a desired shape, often called a "green part."

The End Goal

The primary goal of sintering is densification and strengthening. As particles fuse, the pores between them shrink or close, increasing the material's density, strength, and structural integrity.

Annealing: Refining an Existing Solid

Annealing is a heat treatment applied to materials that are already in a solid form. Its purpose is not to create the part, but to improve it.

The Core Mechanism

Annealing involves heating a material above its recrystallization temperature. This gives the atoms in the crystal lattice enough energy to rearrange themselves from a strained, distorted state into a more orderly, stress-free structure. This is followed by a controlled cooling period.

The Starting Material

The process starts with a solid object that has accumulated internal stresses. This stress often comes from processes like cold working (e.g., bending or rolling metal), casting, or welding.

The End Goal

The main objective of annealing is to increase ductility and reduce hardness. By relieving internal stresses, the process makes a material less brittle and easier to shape, machine, or bend without fracturing.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Nuances

While their purposes are distinct, both are precision thermal processes where control is paramount. Understanding their limitations is key to successful application.

Sintering's Challenge: Porosity

Achieving 100% density through sintering is extremely difficult. Most sintered parts will have some level of residual porosity, which can become a point of mechanical failure if not properly controlled. The process can also be highly sensitive to atmospheric conditions, sometimes requiring specific gases like hydrogen or nitrogen to prevent oxidation.

Annealing's Risk: Unwanted Property Changes

While annealing relieves stress, improper control can be detrimental. Heating for too long or at too high a temperature can cause excessive grain growth, which can sometimes reduce the material's strength or negatively impact other desired properties. The cooling rate is also a critical variable that must be managed precisely.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Selecting the correct thermal process depends entirely on what you need to achieve with your material.

- If your primary focus is creating a solid component from a metal or ceramic powder: Sintering is the essential formative process required to bond the particles.

- If your primary focus is improving the workability of a metal that has become brittle from cold working: Annealing is the corrective treatment needed to restore its ductility.

- If your primary focus is relieving stresses from a welded joint or cast part to prevent cracking: Annealing is the necessary finishing step to ensure long-term integrity.

Ultimately, understanding this distinction between forming a material and refining its properties is key to controlling its final performance.

Summary Table:

| Process | Primary Goal | Starting Material | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sintering | Densification & Strengthening | Powder (e.g., metal, ceramic) | Heating below melting point to fuse particles |

| Annealing | Stress Relief & Increased Ductility | Solid Object (e.g., cold-worked metal) | Heating above recrystallization temperature for atomic rearrangement |

Unsure which thermal process is right for your application? The experts at KINTEK are here to help. We specialize in providing the precise lab equipment and consumables needed for both sintering and annealing processes. Whether you are developing new materials or refining existing components, our solutions ensure optimal temperature control and consistent results. Contact us today via the form below to discuss how we can support your laboratory's specific needs in powder metallurgy, ceramics, or metalworking.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace with 9MPa Air Pressure

- Vertical Laboratory Tube Furnace

- Controlled Nitrogen Inert Hydrogen Atmosphere Furnace

People Also Ask

- What is vacuum sintering? Achieve Unmatched Purity and Performance for Advanced Materials

- Why is sintering easier in the presence of a liquid phase? Unlock Faster, Lower-Temperature Densification

- What is sintering reaction? Transform Powders into Dense Solids Without Melting

- How does precise temperature control affect FeCoCrNiMnTiC high-entropy alloys? Master Microstructural Evolution

- Why must green bodies produced via binder jetting undergo treatment in a vacuum sintering furnace?