The limitations of static electrolysis become immediately apparent when working with three-dimensional substrates. While a static cell relies on passive diffusion, an electrochemical flow reactor is required for lead dioxide (PbO2) deposition because it actively circulates the electrolyte through the porous electrode structure. This forced convection is the only reliable method to mitigate diffusion limitations and ensure active ions penetrate deep into the material for a uniform internal coating.

In 3D electrodeposition, mass transport is the bottleneck. A flow reactor overcomes this by using a pump to force active ions deep into the substrate, preventing ion depletion inside the porous structure and ensuring a uniform coating throughout.

The Challenge of Deep Penetration

To understand why a flow reactor is necessary, you must first understand the failure mode of static cells when applied to porous materials like Reticulated Vitreous Carbon (RVC).

The Limits of Diffusion

In a static electrolytic cell, the movement of ions to the electrode surface relies primarily on diffusion. This process is relatively slow and passive.

Ion Depletion Zones

When depositing on a 3D structure, the ions on the outer surface are consumed and replenished relatively easily. However, the electrolyte deep inside the pores becomes depleted of active species.

The "Dog-Bone" Effect

Because fresh ions cannot diffuse into the center fast enough to match the reaction rate, deposition occurs almost exclusively on the outer shell. This leaves the internal surfaces uncoated or poorly coated, compromising the performance of the electrode.

How Flow Reactors Solve Mass Transport

The introduction of an electrochemical flow reactor fundamentally changes the physics of the deposition process from diffusion-dominated to convection-dominated.

Forced Electrolyte Circulation

A flow reactor does not merely hold the liquid; it pushes the electrolyte directly through the porous body of the electrode. This creates a constant turnover of fluid at the microscopic level inside the pores.

The Role of the Peristaltic Pump

By pairing the reactor with a peristaltic pump, you maintain a constant, controlled flow rate. This mechanical force overcomes the resistance of the porous structure.

Mitigating Non-Uniformity

Because fresh, ion-rich electrolyte is constantly forced into the depths of the RVC, the concentration of active species remains consistent throughout the material. This ensures that the reaction rate is uniform across both the internal and external surfaces.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While the flow reactor is superior for performance, it introduces operational considerations that differ from static setups.

Complexity vs. Quality

A static cell is a simple "beaker" setup, whereas a flow reactor requires plumbing, pumps, and careful sealing. You are trading simplicity for the technical necessity of uniformity.

Optimization Requirements

Using a flow reactor requires you to tune the flow rate. If the flow is too low, you revert to diffusion problems; if too high, you may introduce turbulence or mechanical stress to the substrate.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

When designing your electrodeposition process, your choice of equipment dictates the quality of your final component.

- If your primary focus is coating complex 3D or porous structures: You must use an electrochemical flow reactor with a peristaltic pump to guarantee internal ion penetration and uniform PbO2 coverage.

- If your primary focus is coating simple, flat 2D surfaces: You may utilize a static electrolytic cell, as diffusion is generally sufficient for planar geometries.

Success in 3D electrodeposition is determined not just by chemistry, but by your ability to control mass transport through fluid dynamics.

Summary Table:

| Feature | Static Electrolytic Cell | Electrochemical Flow Reactor |

|---|---|---|

| Mass Transport | Passive Diffusion (Slow) | Forced Convection (Fast) |

| Ion Distribution | Depletion in deep pores | Uniform throughout structure |

| Coating Quality | Non-uniform "Dog-Bone" effect | Consistent internal/external coating |

| Best Suited For | Simple 2D flat surfaces | Complex 3D / Porous structures |

| Complexity | Low (Beaker setup) | High (Requires pumps & plumbing) |

Elevate Your Electrochemical Research with KINTEK

Precision in 3D electrodeposition demands more than just chemistry—it requires advanced fluid dynamics. At KINTEK, we specialize in providing high-performance electrolytic cells, electrodes, and laboratory equipment tailored for the most demanding research applications.

Whether you are coating complex RVC structures or developing next-generation batteries, our comprehensive portfolio—from flow reactors and peristaltic pumps to high-temperature furnaces and pressure reactors—ensures your lab has the tools to achieve uniform, repeatable results.

Ready to optimize your deposition process? Contact our technical experts today to find the perfect equipment solution for your laboratory needs.

References

- Rosimeire Martins Farinos, Luís A.M. Ruotolo. Development of Three-Dimensional Electrodes of PbO<sub>2</sub>Electrodeposited on Reticulated Vitreous Carbon for Organic Eletrooxidation. DOI: 10.5935/0103-5053.20160162

This article is also based on technical information from Kintek Solution Knowledge Base .

Related Products

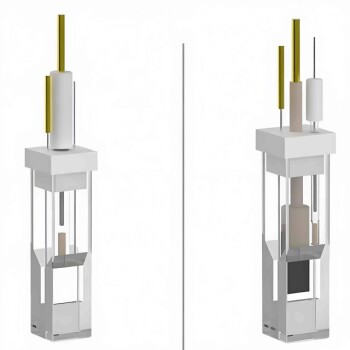

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell Gas Diffusion Liquid Flow Reaction Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

People Also Ask

- What types of electrodes are used in the electrolytic cell? Choose the Right System for Your Lab

- What are the operational procedures and safety precautions during an experiment with an acrylic electrolytic cell? Essential Guide for Lab Safety

- What functions do electrolytic cells perform in PEC water splitting? Optimize Your Photoelectrochemical Research

- What is the function of a glass tube electrochemical cell in simulated dental implant corrosion? Master Oral Simulation

- How does a laboratory electrochemical anodization setup achieve the controlled growth of titanium dioxide nanotubes?

- Why is an electrolytic etching system required for Incoloy 800HT? Master Precision Microstructural Visualization

- What is the function of a single-compartment flow electrochemical reactor? Optimize Your Chlorate Synthesis Today

- What is the function of an electrolytic cell in tritium enrichment? Boost Detection Limits in Water Analysis