In engineering, as in life, we are often seduced by the simplest path.

If you want to measure the electrical properties of a coated material, the intuitive approach is to connect a wire to one side, a wire to the other, and read the numbers. A simple loop. A two-electrode system.

But in the delicate world of electrochemistry, simplicity is often a mask for noise.

When evaluating a coating’s resistance to corrosion or degradation, you are asking a specific question: What is happening at the surface of this material?

To get the answer, you must fight a fundamental law of physics: The act of measuring often changes the thing being measured.

This is why the three-electrode system is not just an industry standard; it is the only way to achieve truth in data.

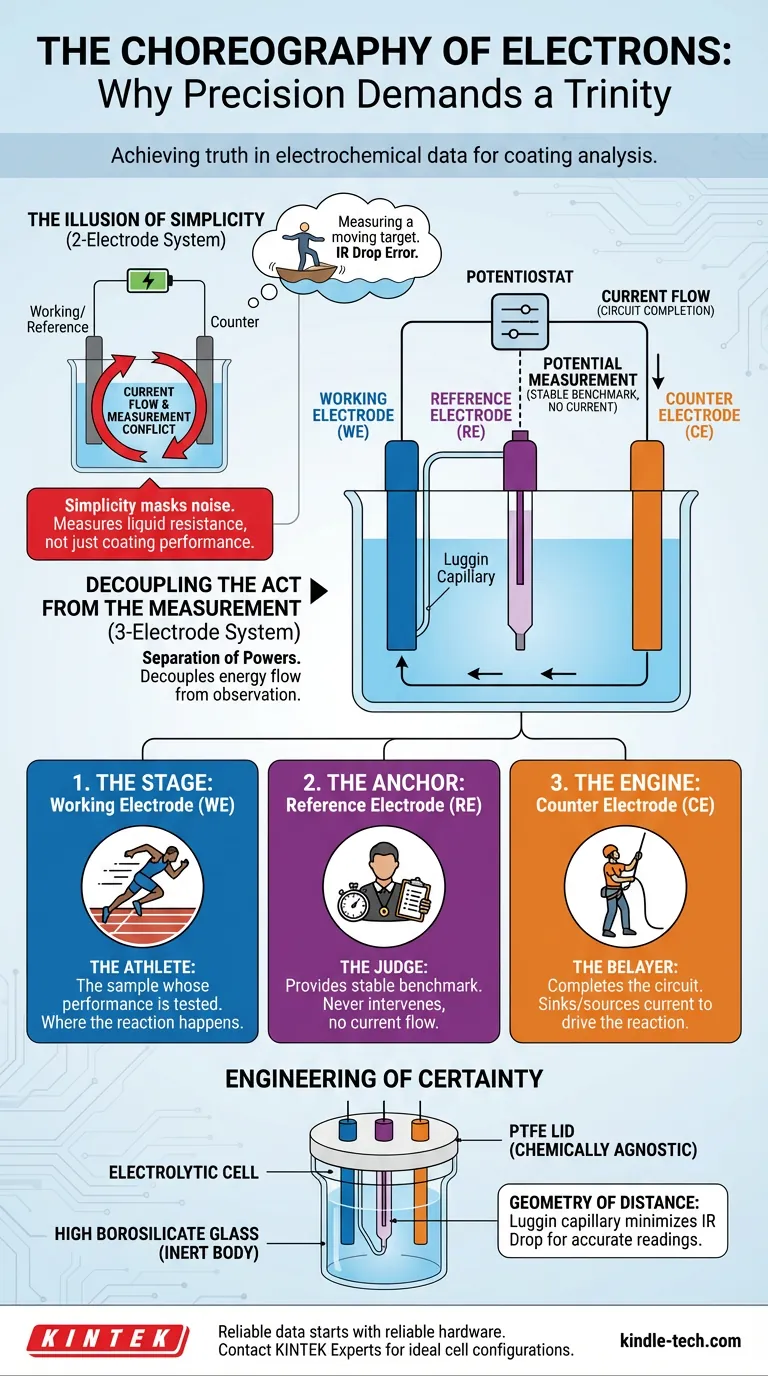

The Illusion of Simplicity

The problem with a two-electrode setup is one of conflict of interest.

In a standard circuit, current must flow to drive the reaction. If you use the same electrode to carry that current and serve as your reference point for voltage, you introduce chaos.

As current passes through an electrode, its potential shifts. It creates a moving target. You are trying to measure the height of a wave while standing on a rocking boat.

Furthermore, as current pushes through the electrolyte solution, it encounters resistance. This creates a voltage drop—known as the IR Drop. In a two-electrode system, this drop is indistinguishable from the data you actually want.

You end up measuring the resistance of the liquid, not just the performance of your coating.

Decoupling the Act from the Measurement

The brilliance of the three-electrode system lies in its separation of powers. It decouples the flow of energy from the observation of potential.

It turns a chaotic brawl into a choreographed dance involving three distinct actors.

1. The Stage: The Working Electrode (WE)

This is your sample. It is the protagonist of the experiment. Whether you are testing a new anti-corrosive paint or a polymer coating, this is where the reaction happens.

We want to know everything about this electrode, and nothing about the others.

2. The Anchor: The Reference Electrode (RE)

This is the conscience of the system.

Its sole purpose is to provide a stable, unchanging benchmark potential. Crucially, virtually no current flows through it.

Because it is isolated from the heavy lifting of the circuit, it never polarizes. It remains rock steady. It allows you to measure the potential of the Working Electrode against a fixed point, regardless of how much current is storming through the rest of the cell.

3. The Engine: The Counter Electrode (CE)

Also known as the auxiliary electrode, this is the workhorse.

The Counter Electrode exists solely to complete the circuit. It sinks or sources whatever current the Working Electrode requires to drive the reaction.

It takes the abuse so the Reference Electrode doesn’t have to.

The Engineering of Certainty

Implementing this trinity requires more than just extra wiring. It requires a physical architecture designed to minimize error.

This is where the design of the electrolytic cell becomes an engineering discipline in itself.

The Geometry of Distance

Even with three electrodes, resistance in the electrolyte can cause errors. To mitigate this, the Reference Electrode is often connected via a Luggin capillary—a fine tube that brings the measurement point extremely close to the surface of the sample.

It minimizes the uncompensated resistance, effectively removing the "liquid tax" from your voltage reading.

The Necessity of Inertness

The vessel itself must not have an opinion.

If your cell body reacts with the electrolyte, it contaminates the data. This is why high-quality cells utilize high borosilicate glass for the body and Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) for the lid. These materials are chemically agnostic. They ensure that the only chemistry you are measuring is the chemistry you intended to study.

Summary: The Roles in the System

To visualize the separation of duties, consider this breakdown:

| Electrode | Role | The "Human" Analogy |

|---|---|---|

| Working (WE) | The Sample | The Athlete: The one whose performance is being tested. |

| Reference (RE) | Measurement | The Judge: Watches closely, never intervenes, provides the score. |

| Counter (CE) | Circuit Completion | The Belayer: Holds the rope and takes the weight so the athlete can move. |

The Cost of Precision

Using a three-electrode system is more complex. It is more sensitive to geometry, purity, and placement. It requires patience.

But the alternative is data that looks correct but is fundamentally flawed. In industries where coating failure can lead to pipeline leaks or structural collapse, "simple" is not an option. "Accurate" is the only metric that matters.

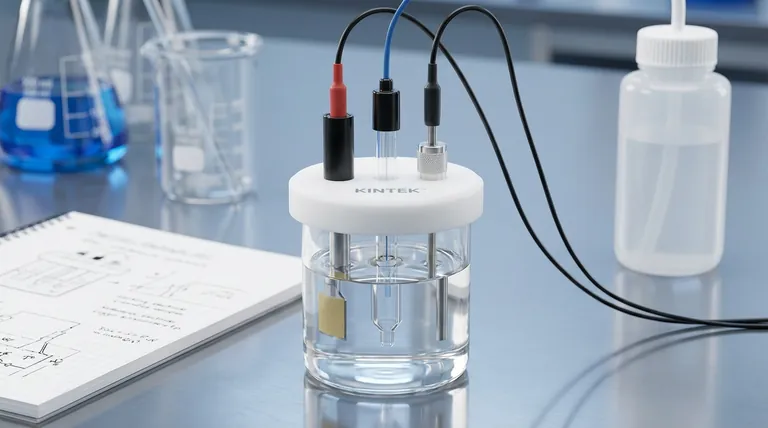

At KINTEK, we understand that reliable data starts with reliable hardware. Our electrolytic cells are engineered to provide the geometric precision and chemical inertness required for rigorous three-electrode analysis.

Whether you are performing Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) or potentiodynamic polarization, you need a system that eliminates noise so you can hear what your materials are trying to tell you.

Don't let your equipment be the variable you didn't account for. Contact Our Experts to discuss the ideal cell configuration for your research.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- H Type Electrolytic Cell Triple Electrochemical Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell Gas Diffusion Liquid Flow Reaction Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

Related Articles

- The Architecture of Control: Mastering the Super-Sealed Electrolytic Cell

- The Silence of the Seal: Why Electrochemical Precision is a Battle Against the Atmosphere

- The Architecture of Silence: Mastering the Super-Sealed Electrolytic Cell

- The Architecture of Precision: Mastering the Five-Port Water Bath Electrolytic Cell

- The Glass Heart of the Experiment: Precision Through Systematic Care