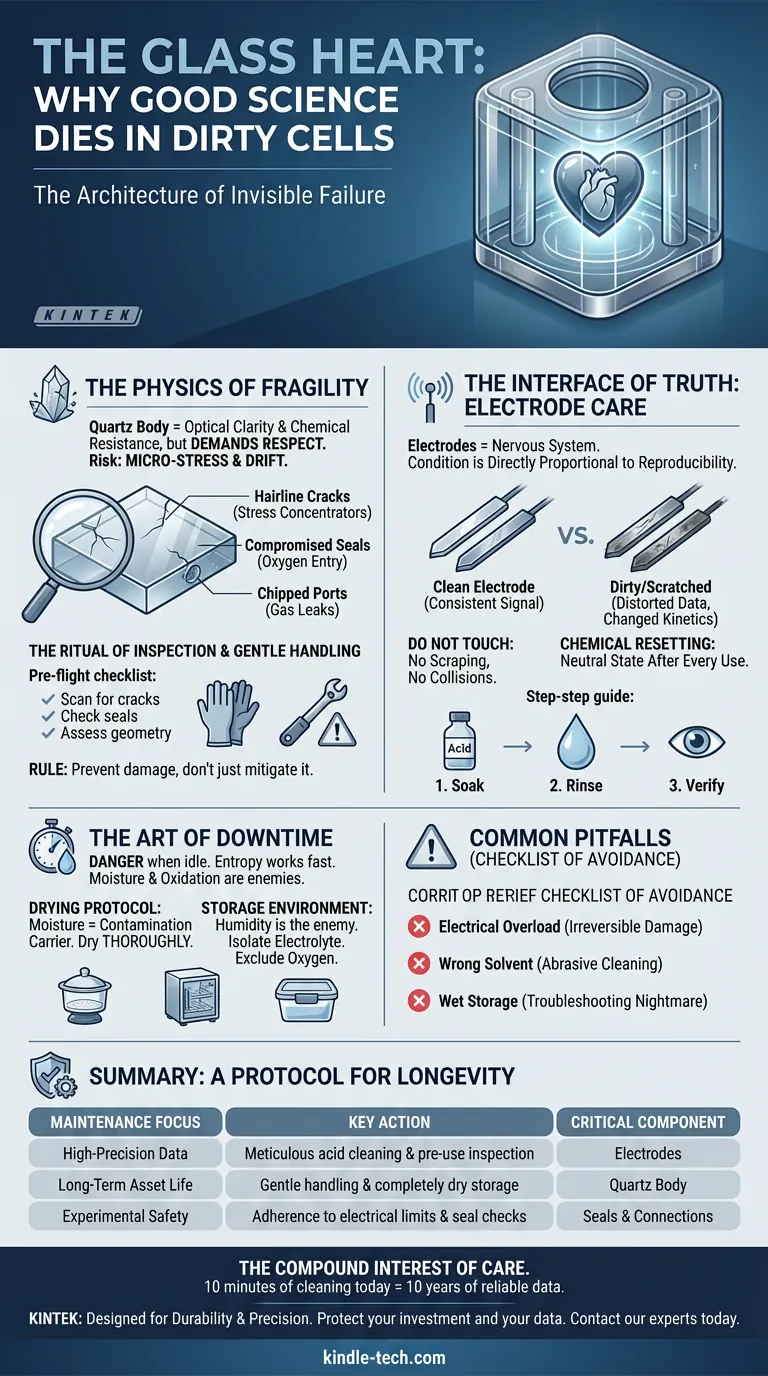

The Architecture of Invisible Failure

In the laboratory, we often obsess over the variables we can control: the voltage, the solute concentration, the temperature. We assume the hardware is a constant.

This is a dangerous assumption.

An all-quartz electrolytic cell is not a static container. It is a dynamic participant in your experiment. Like a camera lens, any scratch, smudge, or residue on its surface distorts the "image" of the data you receive.

The failure of a complex electrochemical system rarely happens with a loud bang. It happens silently. It happens because of drift.

Data drift is the result of thousands of microscopic insults to the equipment. A hairline crack in the quartz. A layer of oxidation on the platinum. A seal that has lost its elasticity.

To prevent this, you need more than a cleaning manual. You need a philosophy of maintenance that treats the cell as the fragile, beating heart of your research.

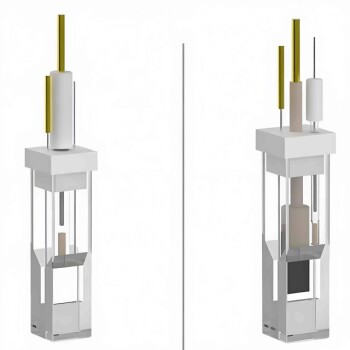

The Physics of Fragility

The cell body is made of quartz. It offers optical clarity and chemical resistance, but it demands respect.

The risk here isn't just that it will shatter on the floor—that is an obvious, manageable risk. The real risk is micro-stress.

The Ritual of Inspection

Before a single drop of electrolyte enters the cell, a visual inspection is mandatory. This is your pre-flight checklist.

- Scan for hairline cracks: These are stress concentrators that lead to catastrophic failure under thermal or physical load.

- Check the seals: Look for brittleness or discoloration. A compromised seal introduces oxygen, the invisible enemy of reduction reactions.

- Assess the geometry: Ensure no ports are chipped, which could prevent a gas-tight seal.

Gentle Handling as a Standard

The principle is simple: Prevent damage rather than mitigate it.

Handling the cell requires a specific mindfulness. The quartz should never experience impact or torsion. When tightening fittings, the force should be firm but never aggressive. You are sealing glass, not steel.

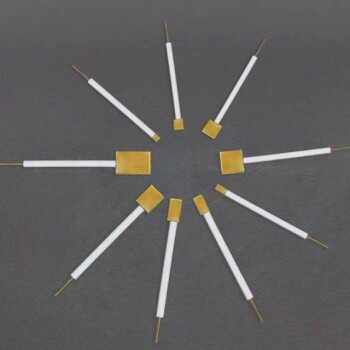

The Interface of Truth: Electrode Care

If the quartz is the body, the electrodes are the nervous system. This is where the signal is generated.

The physical condition of the electrode surface is directly proportional to the reproducibility of your results. A scratched electrode changes the active surface area. A dirty electrode changes the electron transfer kinetics.

The "Do Not Touch" Rule

Physical integrity is paramount.

- No scraping: Never use abrasive materials to clean the surface.

- No collisions: Ensure the counter and working electrodes never touch during insertion or removal.

Chemical Resetting

You cannot see molecular contamination, but your potentiostat can feel it. Electrodes must be reset to a neutral state after every use.

For noble metals like platinum, the standard protocol is rigorous:

- Soak: Use a dilute acid (e.g., 1M nitric acid) to dissolve inorganic residues.

- Rinse: Follow with a complete rinse using deionized water.

- Verify: Visually check for any remaining discoloration.

The Art of Downtime

The most dangerous time for an electrolytic cell is when it is not being used.

Entropy works fastest when equipment is idle. Moisture settles. Salts crystallize. Metal oxidizes.

The Drying Protocol

Moisture is the carrier of contamination. After cleaning, the cell must be dried thoroughly. Any residual water becomes a breeding ground for oxides or a solvent for airborne contaminants.

The Storage Environment

Where you put the cell matters as much as how you clean it.

- Humidity is the enemy: Store components in a non-humid environment.

- Isolate the electrolyte: Never store the cell filled with solution. Pour it out, clean the vessel, and store the fluid separately.

- Oxygen exclusion: For sensitive metal electrodes, store them in a protective solution or an oxygen-free box to prevent surface passivation.

Common Pitfalls (The Checklist of Avoidance)

Smart people make simple mistakes because they rush. Here are the systemic errors that ruin equipment:

- Electrical Overload: Exceeding the rated current or voltage doesn't just ruin the experiment; it physically alters the electrode surface, sometimes irreversibly.

- The Wrong Solvent: Using an abrasive cleaning agent on a polished electrode is like cleaning eyeglasses with sandpaper.

- Wet Storage: Leaving a cell wet "for just one night" often leads to weeks of troubleshooting later.

Summary: A Protocol for Longevity

Your maintenance strategy should align with your scientific goals.

| Maintenance Focus | Key Action | Critical Component |

|---|---|---|

| High-Precision Data | Meticulous acid cleaning & pre-use inspection | Electrodes |

| Long-Term Asset Life | Gentle handling & completely dry storage | Quartz Body |

| Experimental Safety | Adherence to electrical limits & seal checks | Seals & Connections |

The Compound Interest of Care

Maintaining an all-quartz cell is an investment. Ten minutes of cleaning today buys you ten years of reliable data.

At KINTEK, we understand this engineering romance. We build our laboratory equipment to the highest standards of durability and precision, but even the best tools rely on the hands that hold them.

Our electrolytic cells are designed to be the robust foundation of your research. When treated with the discipline described above, they become invisible—allowing you to see only the science.

Protect your investment and your data. Contact our experts today to discuss the right electrolytic systems for your specific application.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Quartz Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Electrochemical Experiments

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell with Five-Port

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

- Super Sealed Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

Related Articles

- The Glass Heart of the Experiment: Precision Through Systematic Care

- The Architecture of Precision: Why Your Electrolytic Cell Specs Matter More Than You Think

- The Art of the Empty Vessel: Preparing Quartz Electrolytic Cells for Absolute Precision

- The Architecture of Precision: Why the Invisible Details Define Electrochemical Success

- The Architecture of Invisibility: Deconstructing the "All-Quartz" Cell