Yes, definitively. Brazing requires significantly higher temperatures than soldering. The internationally recognized threshold is 840°F (450°C); processes that use a filler metal melting above this temperature are defined as brazing, while those using a filler metal melting below it are defined as soldering.

The core difference is not just the temperature itself, but what that temperature enables. The higher heat of brazing creates a fundamentally different, much stronger metallurgical bond, while soldering creates a simpler surface-level adhesion.

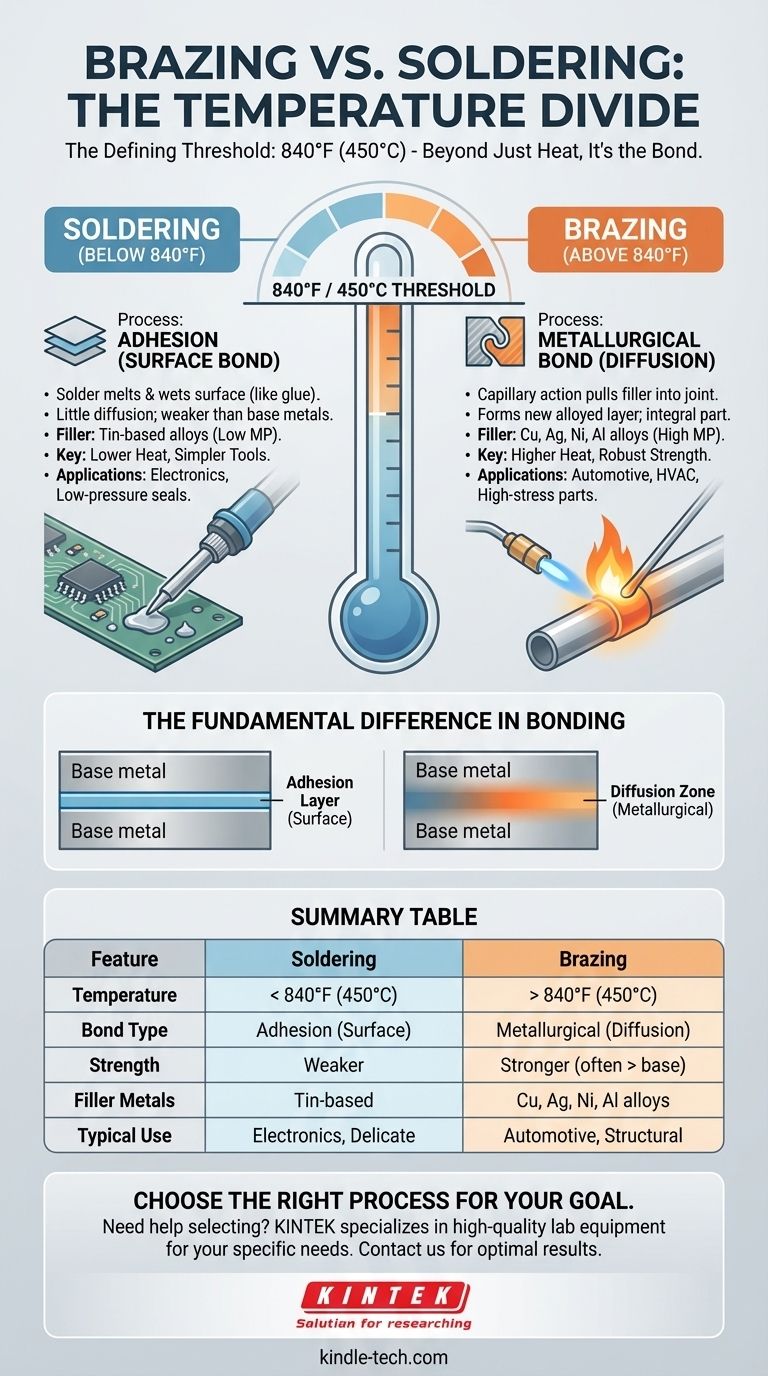

The Defining Difference: The 840°F (450°C) Threshold

The temperature is the critical factor that dictates the physics of the joint and the type of filler metal used.

What Happens in Soldering (Below 840°F)

Soldering is essentially a process of adhesion. The filler metal, or solder, melts and "wets" the surfaces of the base metals, much like glue sticking two pieces of paper together.

There is very little diffusion or alloying between the solder and the base parts. The strength of the joint is limited to the strength of the solder itself, which is almost always much weaker than the metals being joined.

What Happens in Brazing (Above 840°F)

Brazing creates a true metallurgical bond. At these higher temperatures, the molten filler metal is pulled into the tight-fitting joint by a powerful force called capillary action.

More importantly, the filler metal actively diffuses into the surface of the base metals, forming a new alloyed layer at the interface. This means the brazed joint becomes an integral part of the assembly, not just a surface connection.

How Temperature Dictates Filler Metal

The required temperature directly influences the filler metal's composition.

Solders are typically tin-based alloys (e.g., tin-lead, tin-silver, tin-copper) with low melting points.

Brazing fillers are stronger alloys based on copper, silver, nickel, or aluminum, which require much higher energy to melt.

The Practical Implications: Strength and Application

The difference between a surface bond and a metallurgical bond has enormous consequences for how these processes are used.

Joint Strength: Soldering's Weaker Bond

Because a soldered joint relies on adhesion, it is best suited for applications where mechanical strength is not the primary concern. It is ideal for creating electrical conductivity or a simple, low-pressure seal.

Joint Strength: Brazing's Robust Bond

A properly executed brazed joint is exceptionally strong. In many cases, the joint area can be as strong as or stronger than the base metals themselves. This makes it suitable for parts that will experience high stress, vibration, or temperature changes.

Typical Applications for Soldering

The low heat input and focus on conductivity make soldering the standard for electronics manufacturing. It is also used in some low-pressure copper plumbing and for joining delicate, heat-sensitive components.

Typical Applications for Brazing

Brazing's strength and durability make it essential in demanding industries. It is widely used for automotive parts (like radiators), HVAC system components, industrial tooling, and even high-end cookware where joints must withstand constant thermal cycling.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Choosing a process is not just about seeking maximum strength; it involves balancing complexity, cost, and risk.

The Cost of Strength: Heat Input and Skill

Brazing's high temperatures require more powerful heat sources like torches or furnaces. This significant heat input poses a risk of warping, distortion, or metallurgical damage to the base metals if not controlled by a skilled operator.

The Benefit of Simplicity: Accessibility of Soldering

Soldering is far more accessible. The low heat requirement means simpler, cheaper tools like a soldering iron or a small torch can be used. The process is more forgiving for beginners and requires less stringent preparation.

Material and Design Constraints

The high heat of brazing makes it unsuitable for joining components with low melting points or for applications like circuit boards where nearby components would be destroyed. The need for a tight joint gap for capillary action also places greater demands on the design and fit-up of the parts.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Your application's primary requirement should dictate your choice between these two powerful joining methods.

- If your primary focus is maximum strength, durability, and performance under stress: Brazing is the superior choice, creating a robust, permanent metallurgical bond.

- If your primary focus is joining heat-sensitive electronics or avoiding base metal distortion: Soldering is the correct process due to its significantly lower and more localized heat input.

- If your primary focus is accessibility and a simple seal for a non-structural bond: Soldering provides an effective and low-cost solution for many general-purpose tasks.

Understanding this fundamental temperature divide is the key to selecting the right joining method for a successful and reliable outcome.

Summary Table:

| Process | Temperature Range | Bond Type | Typical Filler Metals | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soldering | Below 840°F (450°C) | Adhesion (surface bond) | Tin-based alloys (e.g., tin-lead, tin-silver) | Electronics, low-pressure plumbing, delicate components |

| Brazing | Above 840°F (450°C) | Metallurgical (diffusion bond) | Copper, silver, nickel, or aluminum alloys | Automotive parts, HVAC systems, industrial tooling, high-stress joints |

Need help selecting the right joining process for your lab or production needs? At KINTEK, we specialize in providing high-quality lab equipment and consumables tailored to your specific requirements. Whether you're working with sensitive electronics or high-strength components, our expertise ensures you get the right tools for optimal results. Contact us today to discuss how we can support your laboratory's success!

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Brazing Furnace

- 1700℃ Controlled Atmosphere Furnace Nitrogen Inert Atmosphere Furnace

- High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory Debinding and Pre Sintering

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

People Also Ask

- What is the fundamental of magnetron sputtering? Master High-Quality Thin Film Deposition

- What is the difference between quenching and heat treatment? Master the Key Metallurgy Process

- What are the various methods of controlling the temperature in resistance oven? Master Precise Thermal Management

- How should frost be removed from Ultra-Low Temperature Freezers? Protect Your Samples and Equipment

- What is RF sputtering? A Guide to Depositing Non-Conductive Thin Films

- What is the boiling point of pyrolysis oil? Understanding Its Complex Boiling Range

- How is additive manufacturing used in industry? Unlock Complex, Lightweight, and Custom Parts

- Why are conventional preservation methods less suitable for biological products? The Critical Risk to Efficacy and Safety