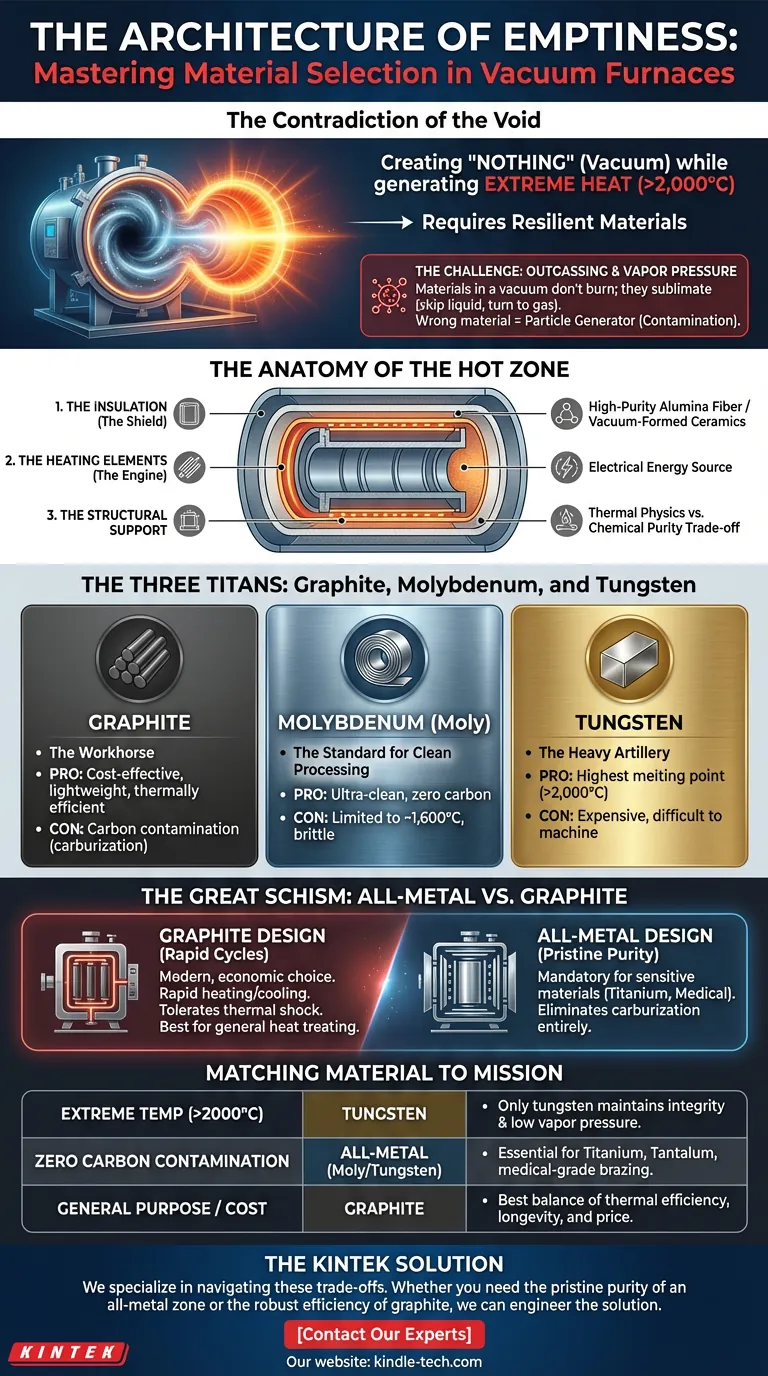

The Contradiction of the Void

A vacuum furnace is an engineering paradox.

Its purpose is to create "nothing"—a space devoid of air and contaminants. Yet, to achieve this emptiness while generating temperatures that can melt steel, we must fill it with materials that are incredibly resilient.

The central challenge in vacuum furnace design isn't just generating heat. That is the easy part.

The hard part is managing extreme energy in a near-total absence of atmosphere without the furnace itself becoming the contaminant.

When materials are heated in a vacuum, they behave strangely. They don't burn; they sublimate. They skip the liquid phase and turn directly into gas, a phenomenon known as outgassing.

If you choose the wrong material, your furnace doesn't just fail; it becomes a particle generator, ruining the very chemistry of the parts you are trying to process.

This is the silent war against Vapor Pressure.

The Anatomy of the Hot Zone

The "Hot Zone" is the heart of the system. It is where the battle between thermal energy and structural integrity takes place.

To win this battle, engineers rely on materials that possess a specific kind of stubbornness: they must refuse to vaporize, even at 2,000°C.

The anatomy of a functional hot zone relies on three primary components:

- The Insulation (The Shield): Usually constructed from high-purity alumina fiber or vacuum-formed ceramics. Its job is to contain the violence of the heat efficiently.

- The Heating Elements (The Engine): The source of energy. Since combustion is impossible in a vacuum, this is purely electrical.

- The Structural Support: Often the same material as the heating elements or insulation shielding.

The materials used here are not arbitrary. They are a calculated trade-off between thermal physics and chemical purity.

The Three Titans: Graphite, Molybdenum, and Tungsten

In the world of high-vacuum processing, only a few materials survive the cut.

The primary requirement is low vapor pressure. If a material releases particles at high heat, the vacuum is compromised.

The industry relies on three distinct materials to solve this:

1. Graphite

Graphite is the workhorse. It is used for heating elements and insulation (graphite fiber).

- The Pro: It is cost-effective, lightweight, and thermally efficient.

- The Con: It is carbon. If your process is sensitive to carbon contamination (carburization), graphite is a dealbreaker.

2. Molybdenum (Moly)

Molybdenum is the standard for "clean" processing.

- The Pro: It provides an ultra-clean environment with zero carbon potential.

- The Con: It is generally limited to temperatures around 1,600°C and is more brittle than graphite.

3. Tungsten

Tungsten is the heavy artillery.

- The Pro: It has the highest melting point of all metals. When you need to go above 2,000°C in a clean environment, Tungsten is the only option.

- The Con: It is expensive and difficult to machine.

The Great Schism: All-Metal vs. Graphite

The most critical decision an engineer makes when configuring a vacuum furnace is the choice of the hot zone.

This decision usually falls into two camps: The All-Metal Design or The Graphite Design.

It is rarely a question of which is "better." It is a question of what your specific application can tolerate.

The Case for Graphite

Modern furnaces often favor graphite. It allows for rapid heating and cooling cycles because materials like graphite fiber insulation have low heat storage capacity. It doesn't crack easily under thermal shock.

For general heat treating where the alloy isn't hyper-sensitive to carbon, graphite is the logical, economic choice.

The Case for All-Metal

Some materials are chemically jealous. They will react with any free carbon particles in the atmosphere.

Medical implants (Titanium) and aerospace superalloys often require a pristine environment. In these cases, an All-Metal Hot Zone (using Molybdenum or Tungsten shields and elements) is mandatory. It eliminates the risk of carburization entirely.

Summary: Matching Material to Mission

When selecting a furnace, you are really selecting a contamination risk profile.

Here is how the trade-offs break down:

| Application Goal | Recommended Hot Zone | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Extreme Temp (>2000°C) | Tungsten | Only tungsten maintains structural integrity and low vapor pressure at these extremes. |

| Zero Carbon Contamination | All-Metal (Moly/Tungsten) | Essential for Titanium, Tantalum, or medical-grade brazing to prevent surface reactions. |

| General Purpose / Cost | Graphite | Offers the best balance of thermal efficiency, longevity, and price for standard applications. |

The KINTEK Solution

There is a romance to the precision required in vacuum processing, but there is no room for error.

Choosing between a molybdenum shield or a graphite element changes the fundamental chemistry of your lab's output. It requires a partner who understands not just the equipment, but the science of the materials inside it.

At KINTEK, we specialize in navigating these trade-offs. We help laboratories configure the precise thermal environment required for their specific materials.

Whether you need the pristine purity of an all-metal zone or the robust efficiency of graphite, we can engineer the solution.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1800℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- 1400℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Horizontal High Temperature Graphite Vacuum Graphitization Furnace

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

Related Articles

- Why Your Ashing Tests Fail: The Hidden Difference Between Muffle and Ashing Furnaces

- Muffle vs. Tube Furnace: How One Choice Prevents Costly Research Failures

- Why Your Furnace Experiments Fail: The Hidden Mismatch in Your Lab

- Comprehensive Guide to Muffle Furnaces: Types, Uses, and Maintenance

- Muffle vs. Tube Furnace: How the Right Choice Prevents Catastrophic Lab Failure