The Invisible Saboteur

In high-stakes engineering, the greatest threat to structural integrity is often invisible.

When you heat metal, you invite oxygen to the party. At high temperatures, oxidation isn't just a surface blemish; it is a structural barrier. It prevents metals from flowing, wetting, and bonding.

To combat this, traditional methods use chemical fluxes—aggressive cleaning agents designed to strip away oxides. But flux is messy. It leaves residue. It creates potential corrosion points. It introduces a variable into a process that demands certainty.

This is why industries like aerospace and medical technology turn to the vacuum furnace.

The vacuum is not merely the absence of air. It is the presence of absolute control.

The Physics of Purity

Brazing in a vacuum furnace fundamentally changes the environment in which the metal exists. By evacuating oxygen and reactive gases, you change the rules of metallurgy.

Removing the Barrier

In a vacuum, oxidation stops. The metal surface remains pristinely active.

Without an oxide layer to block it, the brazing filler metal can flow freely. Driven by capillary action, it wetted the base metal instantly, creating a joint that is not just "stuck" together, but metallurgically unified.

The Flux-Free Advantage

Because the environment is chemically inert, there is no need for flux.

This eliminates the risk of flux entrapment—tiny pockets of chemical residue inside the joint that can lead to failure years down the line. The result is a part that comes out of the furnace bright, clean, and stronger than the parent material itself.

The Engineer’s Trap: Vapor Pressure

However, a vacuum is a harsh environment for certain elements. This is where physics creates a distinct boundary between success and catastrophic failure.

A vacuum dramatically lowers the boiling point of materials.

Most structural metals (like stainless steel) handle this fine. But elements with high vapor pressure will not survive. Instead of melting and flowing, they will "boil off" (outgas) into the vacuum chamber.

The Case Against Brass

This is why you never braze brass in a vacuum.

Brass contains zinc. Zinc has an incredibly high vapor pressure. Under vacuum and heat, the zinc violently vaporizes out of the alloy.

This has two expensive consequences:

- Structural Ruin: The brass part becomes porous and brittle as the zinc leaves its matrix.

- Furnace Contamination: The vaporized zinc coats the interior of the furnace, ruining the heating elements and shielding for future cycles.

The same rule applies to cadmium and lead. In the silence of the vacuum, these elements scream.

Selecting the Right Environment

Engineering is the art of trade-offs. The decision to use a vacuum furnace comes down to understanding the personality of your materials.

If you are working with superalloys, stainless steel, or titanium, the vacuum is your best tool. It offers:

- Uniform heating: Minimizing thermal distortion.

- Process versatility: The ability to anneal and braze in a single cycle.

- Unmatched purity: Critical for parts that go into the human body or into orbit.

If your assembly involves volatile elements like zinc, you must stay in the atmosphere (using positive pressure or inert gas).

Summary: The Decision Matrix

| Factor | Vacuum Brazing Impact |

|---|---|

| Oxidation | Eliminated completely without chemicals. |

| Joint Quality | Void-free, high-strength metallurgical bonds. |

| Cleanliness | Parts emerge bright and scaleless; no post-cleaning required. |

| Material Risks | High Risk: Brass, Zinc, Cadmium (Vaporization). |

| Ideal Materials | Stainless Steel, Superalloys, Titanium. |

Conclusion

The difference between a working joint and a failed component often lies in the microscopic space between two metals.

Vacuum brazing offers a way to close that space with perfect predictability. It removes the variables that cause failure—oxygen, flux, and impurities—leaving only the physics of the bond.

At KINTEK, we understand that the equipment you use defines the ceiling of your capabilities. Whether you are annealing aerospace components or brazing medical devices, our high-performance vacuum furnaces provide the precise environment your materials demand.

Do not leave your joint integrity to chance. Contact Our Experts today to define the perfect thermal process for your application.

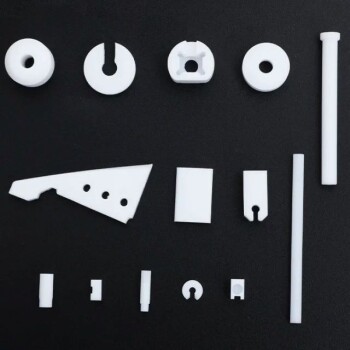

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Hot Press Furnace Machine for Lamination and Heating

- Graphite Vacuum Furnace High Thermal Conductivity Film Graphitization Furnace

- Ultra-High Temperature Graphite Vacuum Graphitization Furnace

Related Articles

- The Architecture of Silence: Mastery Through Total Environmental Control

- The Architecture of Emptiness: Achieving Metallurgical Perfection in a Vacuum

- Your Vacuum Furnace Hits the Right Temperature, But Your Process Still Fails. Here’s Why.

- Your Furnace Hit the Right Temperature. So Why Are Your Parts Failing?

- The Hidden Variable: Why Your Vacuum Furnace Results Are Inconsistent, and How to Fix Them for Good