The Architecture of Trust

In electrochemical research, you are rarely fighting against the laws of physics. Usually, you are fighting against yourself.

Specifically, you are fighting the "ghosts" of previous experiments.

The most dangerous result in a laboratory is not the one that is obviously wrong. It is the result that looks plausible but is subtly influenced by an invisible variable: residue.

An electrolytic cell is not merely a container; it is a stage. Every time you run an experiment, you change the environment of that stage. If you fail to reset it perfectly, the data you collect today is actually a composite of today’s chemistry and yesterday’s negligence.

The standard cleaning procedure for aqueous solution experiments is not a chore. It is a ritual of calibration.

Here is how to ensure your equipment tells you the truth.

The Enemy is Memory

We tend to think of glass and metal as impermeable, static materials. In reality, at the microscopic level, they are landscapes that hold onto history.

When an electrolyte solution evaporates, it leaves behind a film of salts and reaction products. This is the cell’s "memory."

If this memory interacts with your next experiment, you are no longer measuring a pure reaction. You are measuring cross-contamination.

The solution is a protocol defined by speed and dilution.

The Standard Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide

Reliability is rarely the result of brilliance. It is the result of consistency. Following this exact sequence prevents the variables you cannot see from destroying the data you need.

1. The Safe Shutdown

Before you clean, you must disconnect.

Always turn off the power to the electrochemical workstation completely. Remove the electrodes only after the circuit is dead.

This is not just about protecting the researcher from electrical arcs; it is about protecting the electrode surfaces from uncontrolled potential spikes during disassembly.

2. The Race Against Evaporation

Once the electrodes are out, the clock starts.

Pour the used electrolyte out immediately.

The most common error in lab maintenance is hesitation. If you allow the solution to sit, water evaporates, and the dissolved salts precipitate onto the cell walls. Once these salts crystallize, they become exponentially harder to remove than when they were in liquid form.

3. The Rule of Three

Rinse the entire interior of the cell with deionized (DI) water. Then do it again. And then again.

Why three times?

One rinse removes the bulk liquid. The second rinse tackles the boundary layer. The third rinse is a statistical necessity. By the third volume change, the concentration of any remaining contaminant is diluted to negligible levels.

This is the difference between "visually clean" and "chemically clean."

4. The Nitrogen Finish

Drying is where many rigorous protocols fail.

You should never air-dry an electrolytic cell. Air contains oxygen, moisture, and floating particulates.

Instead, use a gentle stream of nitrogen gas.

Nitrogen serves two purposes:

- Inertness: It does not react with the cell surface.

- Velocity: It physically displaces water droplets before they can evaporate.

Evaporation leaves behind "water stains"—mineral deposits that alter the surface area and conductivity of the cell. Nitrogen drying leaves nothing but the substrate.

The Cost of Cutting Corners

Why do researchers skip these steps? Because they seem redundant.

However, the cost of these shortcuts is high:

- Improper Drying: Residual water dilutes your next electrolyte, shifting the concentration.

- Compressed Air: Often contains oil from the compressor, introducing organic contamination.

- Heat Drying: Can induce thermal stress in precision glass or sealants.

Precision Requires Partners

A clean cell is the silent, essential partner in every successful experiment. It provides the baseline of zero that allows your data to mean something.

At KINTEK, we understand that your research is only as good as the tools you trust. From high-purity consumables to robust electrolytic cells designed for rigorous cleaning cycles, we build equipment that respects the scientific method.

Whether you are performing high-precision quantitative analysis or qualitative demonstrations, the integrity of your hardware dictates the integrity of your results.

Summary of Best Practices

| Step | Action | The "Why" |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Safe Shutdown | Prevents electrical hazards and electrode damage. |

| 2 | Immediate Removal | Prevents the formation of stubborn salt crusts. |

| 3 | Triple DI Rinse | Mathematically guarantees contaminant dilution. |

| 4 | Nitrogen Dry | Prevents mineral deposits (water stains). |

Don't let invisible variables compromise your work. Contact Our Experts today to discuss how KINTEK's laboratory solutions can support your pursuit of uncompromised data.

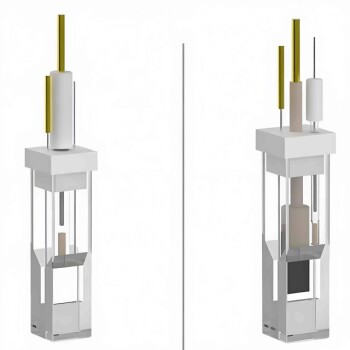

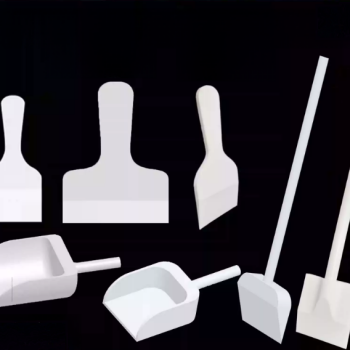

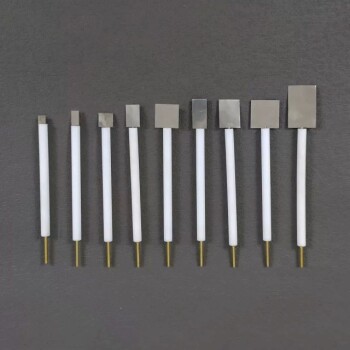

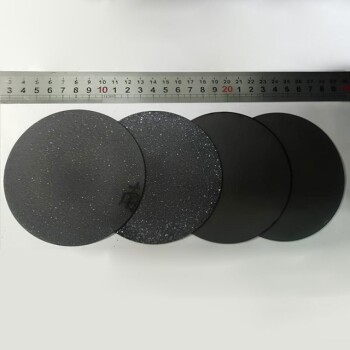

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

- PTFE Electrolytic Cell Electrochemical Cell Corrosion-Resistant Sealed and Non-Sealed

- Side Window Optical Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Customizable PEM Electrolysis Cells for Diverse Research Applications

- Thin-Layer Spectral Electrolysis Electrochemical Cell

Related Articles

- Understanding Flat Corrosion Electrolytic Cells: Applications, Mechanisms, and Prevention Techniques

- The Transparency Paradox: Mastering the Fragile Art of Electrolytic Cells

- The Art of Isolation: Why Super-Sealed Cells Define Modern Electrochemistry

- Understanding Saturated Calomel Reference Electrodes: Composition, Uses, and Considerations

- The Architecture of Precision: Why the Invisible Details Define Electrochemical Success