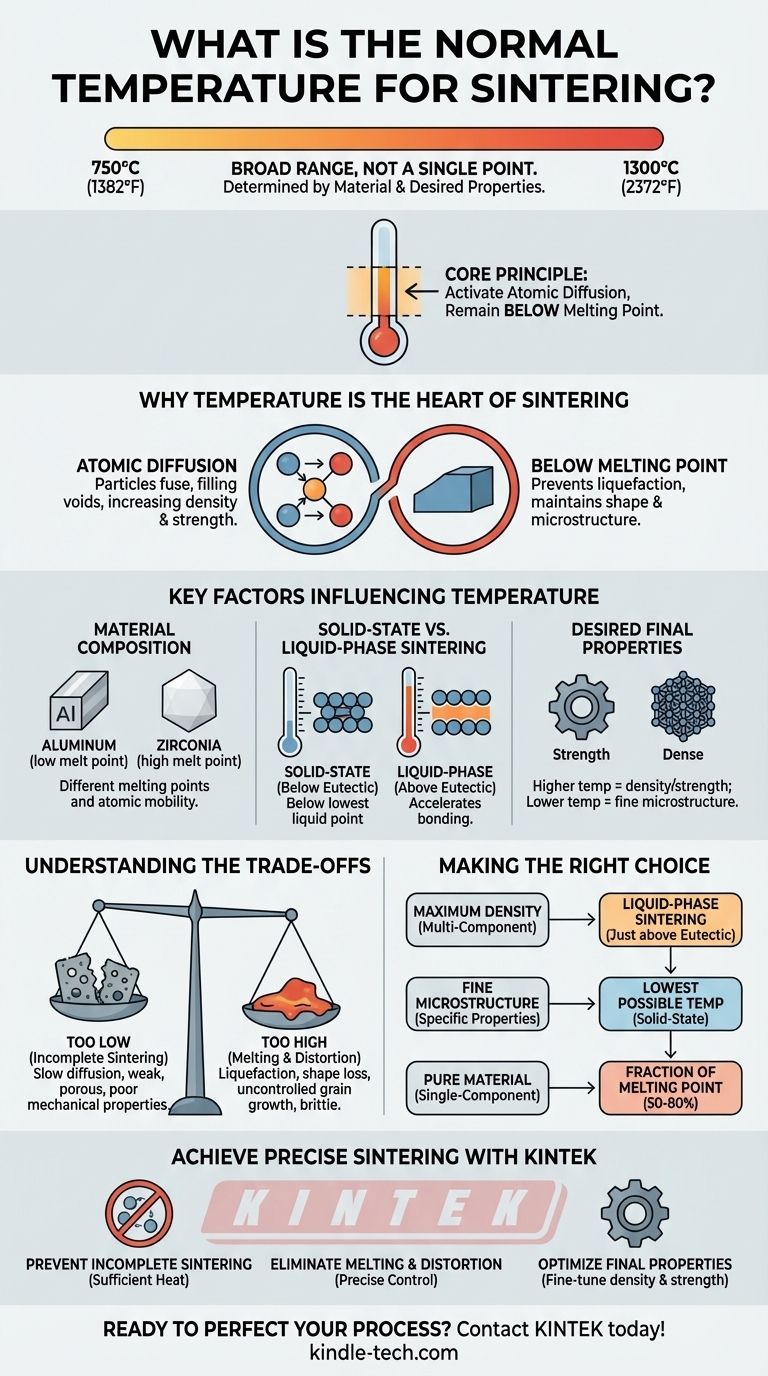

In short, there is no single "normal" temperature for sintering. The process typically operates within a broad range of 750°C to 1300°C (1382°F to 2372°F). The precise temperature is not arbitrary; it is carefully determined by the specific material being processed and the final properties you aim to achieve.

The core principle of sintering is to select a temperature high enough to activate atomic diffusion—allowing particles to bond—but low enough to remain safely below the material's full melting point to prevent it from turning into a liquid.

Why Temperature is the Heart of Sintering

Sintering is a thermal process that uses heat to bond particles of a material, like a metal or ceramic powder, into a solid, coherent mass. Temperature is the primary lever that controls this transformation.

The Goal: Atomic Diffusion

At the right temperature, atoms gain enough energy to move across the boundaries of individual particles. This atomic diffusion is what fills the voids between particles, causing them to fuse together and increase the material's density and strength.

The Constraint: The Melting Point

The goal is to bond the particles, not to melt them. The chosen sintering temperature must always be below the material's melting point. Exceeding this limit would cause the material to liquefy, losing its shape and the desired microstructure.

Key Factors Influencing Sintering Temperature

The ideal temperature is a function of the material's intrinsic properties and the desired outcome.

Material Composition

Different materials have vastly different melting points and atomic mobility. For example, a low-melting-point metal like aluminum will sinter at a much lower temperature than a high-temperature ceramic like zirconia.

Solid-State vs. Liquid-Phase Sintering

The process changes if a small amount of liquid is intentionally formed. The eutectic temperature is the lowest temperature at which a liquid can exist in a multi-component system.

If the operating temperature is below this point, it is solid-state sintering. If it's above this point, it becomes liquid-phase sintering, where the liquid phase can accelerate the bonding and densification process significantly.

Desired Final Properties

The final temperature directly impacts the final product. Higher temperatures within the safe range typically lead to greater density and strength but can also cause unwanted grain growth, which might reduce toughness. Engineers carefully select a temperature to balance these competing characteristics.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Selecting the wrong temperature can lead to a completely failed process. The window for successful sintering is often precise.

Consequence of Temperature Being Too Low

If the temperature is insufficient, atomic diffusion will be too slow. This results in incomplete sintering, leading to a product that is porous, weak, and has poor mechanical properties because the particles have not adequately bonded.

Consequence of Temperature Being Too High

If the temperature gets too close to or exceeds the melting point, the material will begin to liquefy. This can cause the part to slump, distort, or lose its intended shape. It also leads to uncontrolled grain growth, often producing a brittle final product.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The correct temperature is always defined by the material and the objective.

- If your primary focus is maximum density in a multi-component system: Consider liquid-phase sintering by operating just above the material's eutectic temperature to accelerate the process.

- If your primary focus is preserving a very fine-grained microstructure for specific properties: Use the lowest possible temperature that still achieves the necessary particle bonding (solid-state sintering).

- If you are working with a pure, single-component material: Your target temperature will be a specific fraction of its absolute melting point, typically between 50% and 80%, determined through material science principles and testing.

Ultimately, successful sintering depends on precise temperature control tailored to your specific material and engineering goals.

Summary Table:

| Factor | Influence on Sintering Temperature |

|---|---|

| Material Composition | Determines base melting point (e.g., Aluminum vs. Zirconia). |

| Sintering Type | Solid-state (below eutectic) vs. Liquid-phase (above eutectic). |

| Desired Properties | Higher temp for density/strength, lower temp for fine microstructure. |

Achieve Precise Sintering with KINTEK

Selecting and maintaining the exact temperature is critical for successful sintering. KINTEK specializes in high-performance lab furnaces that deliver the precise temperature control and uniformity your process demands.

We provide the reliable equipment you need to:

- Prevent Incomplete Sintering: Avoid weak, porous parts by ensuring sufficient heat for proper atomic diffusion.

- Eliminate Melting and Distortion: Our precise controls keep temperatures safely below melting points to preserve part shape.

- Optimize Final Properties: Fine-tune density, strength, and microstructure for your specific application.

Ready to perfect your sintering process? Contact our experts today to find the ideal furnace solution for your laboratory's material science goals.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Laboratory Muffle Oven Furnace Bottom Lifting Muffle Furnace

- 1700℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace with 9MPa Air Pressure

People Also Ask

- What is the primary advantage of using a tube furnace? Achieve Superior Temperature and Atmosphere Control

- How does a tube furnace work? Master Precise Thermal and Atmospheric Control

- Why is an Alumina Ceramic Tube Support Necessary for 1100°C Experiments? Ensure Data Accuracy and Chemical Inertness

- What is the pressure on a tube furnace? Essential Safety Limits for Your Lab

- What is a tubular furnace used for? Precision Heating for Material Synthesis & Analysis