The laboratory drying oven serves as a critical stabilization tool in the preparation of Hyper-cross-linked Polystyrene (HPS) catalysts. Its primary function is the controlled removal of residual complex solvents—specifically tetrahydrofuran, methanol, and water—from the porous structure of the support material. By maintaining a precise temperature range between 70°C and 85°C, the oven facilitates the transition from a wet impregnated mixture to a solid catalyst precursor ready for activation.

Core Takeaway The drying phase is the defining moment for active site distribution. It is not simply about removing liquid, but about managing the evaporation rate to ensure metal precursors deposit uniformly across the polymer's micropores and mesopores, rather than aggregating due to thermal shock.

The Mechanism of Controlled Solvent Removal

Targeting Complex Solvents

In the impregnation process, the HPS support is saturated with solvents that must be removed without damaging the structure.

The drying oven is specifically utilized to eliminate complex solvents such as tetrahydrofuran (THF), methanol, and water.

Preserving Pore Architecture

The drying process occurs within the intricate network of the polymer.

The oven ensures that these solvents are evacuated from the micropore and mesopore surfaces effectively. This clears the physical space required for the metal salt precursors to anchor themselves onto the support.

Ensuring Uniform Metal Distribution

Anchoring Metal Precursors

The ultimate goal of the impregnation method is to leave behind a specific metal loading.

By maintaining a constant temperature (70°C–85°C), the drying oven ensures that metal salt precursors are left behind in a uniform layer. This uniform deposition is essential for the catalyst's future performance.

Preventing Component Segregation

How you dry the material is just as important as the fact that you dried it.

If solvents evaporate too quickly, the metal components tend to migrate and clump together, a defect known as component segregation. The controlled heating of the oven prevents this rapid evaporation, keeping the distribution homogeneous.

Understanding the Trade-offs

The Risk of Rapid Evaporation

There is often a temptation to accelerate drying times by increasing the temperature.

However, exceeding the recommended 85°C upper limit poses a significant risk. Higher temperatures can trigger rapid solvent boiling, which physically forces the metal precursors out of the pores and leads to uneven, segregated active sites.

Preparation for Reduction

The drying oven is not the final step; it is a preparatory stage.

The material must be perfectly dried to be ready for the subsequent high-temperature reduction stage. Any residual solvent left due to insufficient drying (temperatures below 70°C) could interfere with the chemical reduction or damage the catalyst structure when high heat is eventually applied.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To maximize the efficiency of your HPS catalyst preparation, apply the following parameters:

- If your primary focus is Active Site Uniformity: Strictly maintain the temperature between 70°C and 85°C to prevent component segregation.

- If your primary focus is Process Safety: Ensure complete removal of flammable solvents like THF and methanol before transferring the material to a high-temperature reduction environment.

Mastering the drying rate is the single most effective way to guarantee a homogeneous and highly active catalyst structure.

Summary Table:

| Parameter | Targeted Solvent/Component | Role in HPS Catalyst Preparation |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature Range | 70°C – 85°C | Stabilizes evaporation to prevent component segregation. |

| Solvent Removal | THF, Methanol, Water | Clears micropores/mesopores for metal salt anchoring. |

| Metal Loading | Salt Precursors | Ensures uniform deposition across the polymer structure. |

| Critical Goal | Active Site Distribution | Prevents thermal shock and aggregation of active sites. |

Elevate Your Catalyst Synthesis with KINTEK Precision

Precise thermal control is the difference between a high-performance catalyst and a failed batch. KINTEK specializes in advanced laboratory equipment designed for the rigorous demands of material science and polymer research.

Whether you are preparing Hyper-cross-linked Polystyrene (HPS) catalysts or developing next-generation energy materials, our comprehensive range of laboratory drying ovens, high-temperature furnaces (muffle, vacuum, and CVD), and high-pressure reactors provides the stability and uniformity your research deserves. From battery research tools to precision crushing and milling systems, we empower labs to achieve reproducible results every time.

Ready to optimize your drying and impregnation protocols? Contact KINTEK today to discuss your laboratory requirements and discover how our specialized equipment can enhance your research efficiency.

References

- Oleg V. Manaenkov, Lioubov Kiwi‐Minsker. An Overview of Heterogeneous Catalysts Based on Hypercrosslinked Polystyrene for the Synthesis and Transformation of Platform Chemicals Derived from Biomass. DOI: 10.3390/molecules28248126

This article is also based on technical information from Kintek Solution Knowledge Base .

Related Products

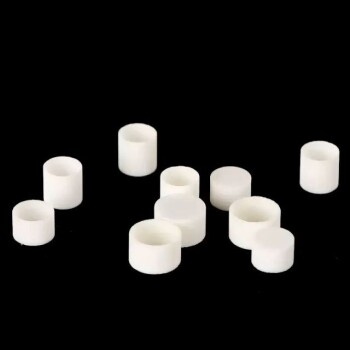

- Laboratory Scientific Electric Heating Blast Drying Oven

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- High Temperature Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory Debinding and Pre Sintering

- 1200℃ Muffle Furnace Oven for Laboratory

- Graphite Vacuum Furnace High Thermal Conductivity Film Graphitization Furnace

People Also Ask

- What conditions does a muffle furnace provide for molten salt energy storage? Expert Simulation for CSP Environments

- Why is a high-temperature muffle furnace necessary for VO2+ doped nanopowders? Achieve 1000°C Phase Transformation

- What is the application of muffle furnace in food industry? Essential for Accurate Food Ash Analysis

- Why is a benchtop constant temperature drying oven used in TiO2 reactor fabrication? Ensure Superior Catalyst Adhesion

- What is the relationship between ash content and moisture content? Ensure Accurate Material Analysis

- What is the function of a high-temperature muffle furnace in (1-x)Si3N4-xAl2O3? Essential Phase Initialization Roles

- What is a sintering oven? The Key to High-Performance Powder Metallurgy and 3D Printing

- Why is a high-precision muffle furnace required for the thermal decomposition of siderite to produce nano-iron oxide?