Laboratory equipment is often viewed as passive—a static tool waiting for a user. But an all-quartz electrolytic cell is different. It is a vessel where three volatile forces meet: fragile materiality, corrosive chemistry, and electrical current.

Success in electrochemistry is rarely about the "big breakthrough." It is usually the result of a thousand small, disciplined actions. The difference between a noise-filled dataset and a pristine voltammogram often comes down to a single air bubble or a fingerprint on an optical window.

To operate this equipment is to manage a system of risks. The procedure is not just a checklist; it is a cycle of observation, respect, and controlled execution.

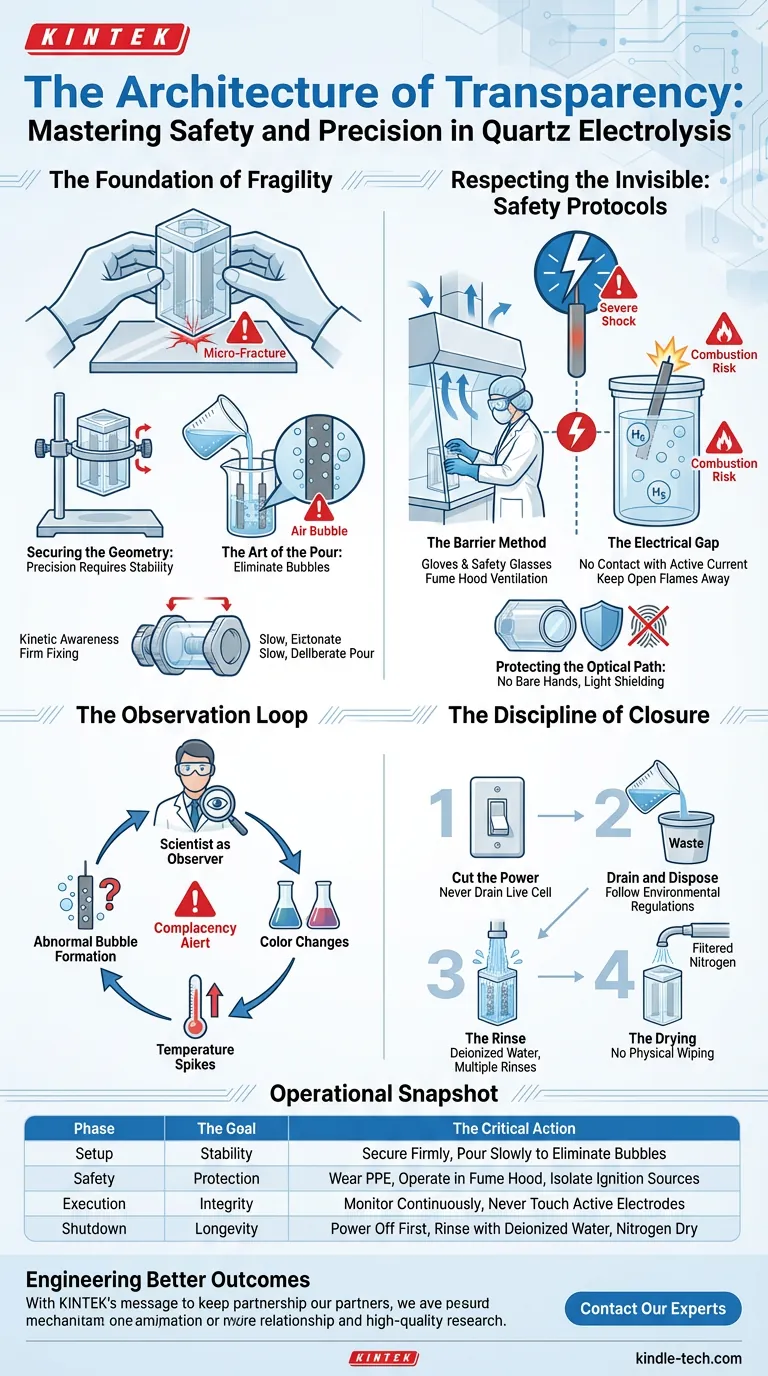

The Foundation of Fragility

The experiment begins long before you turn on the power supply. It begins with how you hold the glass.

Quartz is optically brilliant but mechanically unforgiving. The first rule of operation is kinetic awareness. Always handle the cell body with two hands. A single moment of distraction while placing it on a hard surface can cause a micro-fracture that compromises the entire vessel.

Securing the Geometry

Precision requires stability. The cell must be positioned on the stand’s base and the fixing knobs tightened firmly.

If the cell wobbles, the electrode immersion depth changes. If the depth changes, the active surface area fluctuates. If the area fluctuates, your data is effectively noise.

The Art of the Pour

Filling the cell is the most critical fluid dynamic moment. You must introduce the electrolyte slowly.

Your enemy here is the air bubble.

Bubbles that cling to electrode surfaces act as insulators. They distort the current density and skew electrochemical measurements. A hasty pour creates bubbles; a slow, deliberate pour ensures continuity.

Respecting the Invisible: Safety Protocols

Safety in a lab is often treated as a compliance issue. In reality, it is an engineering constraint. You are working with a device that conducts electricity through liquids that burn skin, housed in glass that shatters.

The Barrier Method

The electrolyte does not care about your experience level. If it is corrosive, it will damage skin.

- Gloves and Safety Glasses: Non-negotiable.

- The Fume Hood: If your electrolyte is volatile or toxic, the air around the cell becomes part of the hazard. Ventilation is your primary defense against inhalation.

The Electrical Gap

Never touch the electrodes or the electrolyte while the current is active. The conductivity that makes the experiment work is the same mechanism that delivers a severe electric shock.

Furthermore, electrolysis often produces gas—frequently Hydrogen. In a closed, unventilated space near a spark, this is not an experiment; it is a combustion engine. Keep open flames far away.

The Observation Loop

Once the current is flowing, the scientist moves from "operator" to "observer."

This is where the psychological challenge arises: Complacency. It is easy to walk away once the parameters are set on the power supply. Do not do this.

You must continuously monitor the cell for:

- Abnormal bubble formation: Indicates side reactions.

- Color changes: Indicates chemical shifts.

- Temperature spikes: Indicates excessive resistance or exothermic reactions.

Protecting the Optical Path

If your cell utilizes optical windows for spectroelectrochemistry, you are protecting a view into the atomic world.

- No bare hands: Oils from skin degrade the quartz transparency.

- Light shielding: When not measuring, cover the cell. Prolonged exposure to high-intensity light can degrade photosensitive reactants or the window material itself.

The Discipline of Closure

Most accidents happen at the end of the day, when mental fatigue sets in and the "real work" feels finished.

The experiment is not over until the cell is pristine.

- Cut the Power: Never drain a live cell.

- Drain and Dispose: Follow environmental regulations strictly.

- The Rinse: Use deionized water. Rinse multiple times. A microscopic residue of today's experiment is the contamination in tomorrow's data.

- The Drying: Use a gentle stream of filtered nitrogen. Physical wiping can scratch the quartz.

Operational Snapshot

For the pragmatic researcher, here is the workflow distilled into its critical components:

| Phase | The Goal | The Critical Action |

|---|---|---|

| Setup | Stability | Secure the cell firmly; pour slowly to eliminate bubbles. |

| Safety | Protection | Wear PPE; operate in a fume hood; isolate ignition sources. |

| Execution | Integrity | Monitor continuously; never touch active electrodes. |

| Shutdown | Longevity | Power off first; rinse with deionized water; nitrogen dry. |

Engineering Better Outcomes

At KINTEK, we understand that high-quality research is a partnership between the scientist and their tools. Our all-quartz electrolytic cells are engineered for transparency and durability, but they rely on your skilled hands to function.

Whether you are optimizing for data integrity, equipment longevity, or absolute safety, the solution begins with the right equipment.

Ready to upgrade your laboratory setup? Contact Our Experts to discuss how KINTEK’s precision equipment can support your research goals.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Double-Layer Water Bath Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell for Coating Evaluation

- Electrolytic Electrochemical Cell Gas Diffusion Liquid Flow Reaction Cell

- PTFE Electrolytic Cell Electrochemical Cell Corrosion-Resistant Sealed and Non-Sealed

- Customizable PEM Electrolysis Cells for Diverse Research Applications

Related Articles

- The Glass Heart of the Experiment: Precision Through Systematic Care

- Exploring the Multifunctional Electrolytic Cell Water Bath: Applications and Benefits

- The Silent Dialogue: Mastering Control in Electrolytic Cells

- The Architecture of Precision: Why the Invisible Details Define Electrochemical Success

- Understanding Flat Corrosion Electrolytic Cells: Applications, Mechanisms, and Prevention Techniques