The first gem-quality synthetic diamonds were produced in 1970 by General Electric (GE) using a specific variation of the High Pressure High Temperature (HPHT) method. By placing graphite and a nickel solvent inside a pressurized pyrophyllite tube, scientists successfully grew diamond crystals up to one carat in size over a week-long process.

Core Takeaway: Achieving gem quality required more than just crushing carbon; it required a controlled temperature gradient. The 1970 GE breakthrough relied on dissolving graphite into a molten metal solvent, which then migrated through the chamber to crystallize onto a diamond seed, strictly mimicking the Earth's natural geological forces.

The GE Production Method (1970)

The creation of these specific stones relied on a precise arrangement of materials and extreme physical forces.

The Reaction Vessel

The process utilized a pyrophyllite tube to contain the reaction. This material was chosen for its ability to transmit pressure while serving as an electrical and thermal insulator.

The Component Arrangement

Inside the tube, thin diamond seeds were placed at each end to act as a foundation for growth. The feed material, graphite, was placed in the center of the tube. A nickel solvent was positioned between the graphite source and the seeds to facilitate carbon transport.

The Growth Environment

The container was subjected to immense pressure, reaching approximately 5.5 GPa (gigapascals), while being heated to high temperatures. This created an environment that forced the graphite to dissolve into the molten nickel solvent.

The Crystallization Process

Over a period of one week, the dissolved carbon migrated from the hot center of the tube toward the cooler ends. It then precipitated out of the metal solvent and crystallized onto the seeds. This resulted in gem-quality stones approximately 5 mm in size (1 carat).

Controlling Color and Purity

The initial results of this process were chemically successful but aesthetically limited.

The Nitrogen Challenge

The first batch of diamonds produced by this method ranged from yellow to brown in color. This was caused by nitrogen contamination present during the growth process, a common issue in early HPHT synthesis.

Achieving Colorless Stones

To produce colorless or "white" diamonds, researchers introduced "getters"—specifically aluminum or titanium. These metals chemically bonded with the nitrogen, removing it from the crystal lattice and allowing clear diamond to form.

Creating Blue Diamonds

Researchers also found they could manipulate the process to create fancy colors intentionally. By adding boron to the growth environment, they successfully produced blue diamonds.

Understanding the Trade-offs: HPHT vs. Modern CVD

While the GE method paved the way, it is important to understand how this historical HPHT method compares to modern alternatives like Chemical Vapor Deposition (CVD).

Metallic Inclusions (HPHT)

The GE method relied on a molten metal solvent (nickel). Consequently, these diamonds often contain microscopic metallic inclusions or impurities derived from the catalyst, which can affect clarity and magnetism.

Growth Mechanics vs. Gas Plasma (CVD)

The HPHT method mimics the Earth's crushing force. In contrast, modern CVD mimics diamond formation in interstellar gas clouds. CVD uses plasma to break down gases at moderate pressures, depositing carbon layer-by-layer, which often allows for higher purity without metal solvents.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

Understanding the history of diamond synthesis helps in evaluating modern synthetic stones.

- If your primary focus is historical accuracy: Note that early "white" synthetics required aluminum or titanium additives to scrub nitrogen, unlike natural stones.

- If your primary focus is identifying synthesis methods: Look for distinct color zoning or metallic inclusions, which are characteristic signatures of the metal-solvent HPHT process used in 1970.

- If your primary focus is purity: Modern CVD is generally preferred over the legacy solvent-based HPHT method because it avoids metallic contamination and offers precise control over crystal growth.

The 1970 GE breakthrough proved that gem-quality diamonds are not just geological accidents, but reproducible feats of chemical engineering.

Summary Table:

| Feature | 1970 GE HPHT Method Details |

|---|---|

| Core Method | High Pressure High Temperature (HPHT) |

| Pressure | Approx. 5.5 GPa |

| Solvent/Catalyst | Molten Nickel |

| Carbon Source | Graphite |

| Growth Time | One week |

| Size Achieved | ~1 carat (5 mm) |

| Color Control | Aluminum/Titanium (for colorless); Boron (for blue) |

Elevate Your Lab Research with KINTEK Precision

Whether you are replicating the historical success of HPHT diamond synthesis or pioneering modern CVD and PECVD processes, KINTEK provides the advanced technology required for success. We specialize in high-performance laboratory equipment, including:

- High-Temperature & Vacuum Furnaces (Muffle, Tube, Rotary, CVD, PECVD, MPCVD)

- High-Temperature High-Pressure Reactors & Autoclaves

- Hydraulic Presses (Pellet, Hot, Isostatic) for material synthesis

- Crushing, Milling & Sieving Systems for feedstock preparation

- Specialized Consumables (Crucibles, Ceramics, and PTFE products)

Ready to advance your material science or battery research? Contact our technical experts today to find the perfect solution for your laboratory’s unique demands.

Related Products

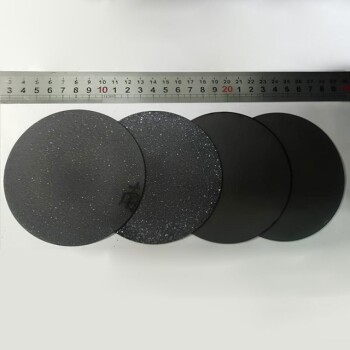

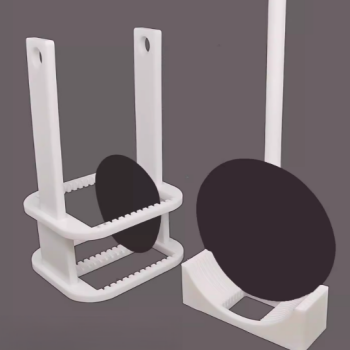

- CVD Diamond Domes for Industrial and Scientific Applications

- Laboratory CVD Boron Doped Diamond Materials

- Cylindrical Resonator MPCVD Machine System Reactor for Microwave Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition and Lab Diamond Growth

- HFCVD Machine System Equipment for Drawing Die Nano-Diamond Coating

- 915MHz MPCVD Diamond Machine Microwave Plasma Chemical Vapor Deposition System Reactor

People Also Ask

- What are the steps of sputtering process? Master Thin-Film Deposition for Your Lab

- What is a sputtering target? The Blueprint for High-Performance Thin-Film Coatings

- What is the physical deposition of thin films? A Guide to PVD Techniques for Material Science

- What is the RF frequency used for sputtering process? The Standard 13.56 MHz Explained

- What is a sputtering target used for? The Atomic Blueprint for High-Performance Thin Films

- What is the effect of substrate on thin films? A Critical Factor for Performance and Reliability

- What is medical device coatings? Enhance Safety, Durability & Performance

- How can thin films be used as coating material? Enhance Surface Properties with Precision Engineering