While essential for achieving high hardness, the primary disadvantages of quenching are the significant risks of distortion, cracking, and a dramatic increase in brittleness. These issues stem from the extreme thermal shock and rapid microstructural changes the material undergoes, which generate immense internal stresses that can compromise the integrity of the part.

Quenching is a controlled shock to a material's system. It trades ductility for hardness, but this transformation introduces powerful internal stresses that, if unmanaged, can lead to distortion, cracking, and premature failure.

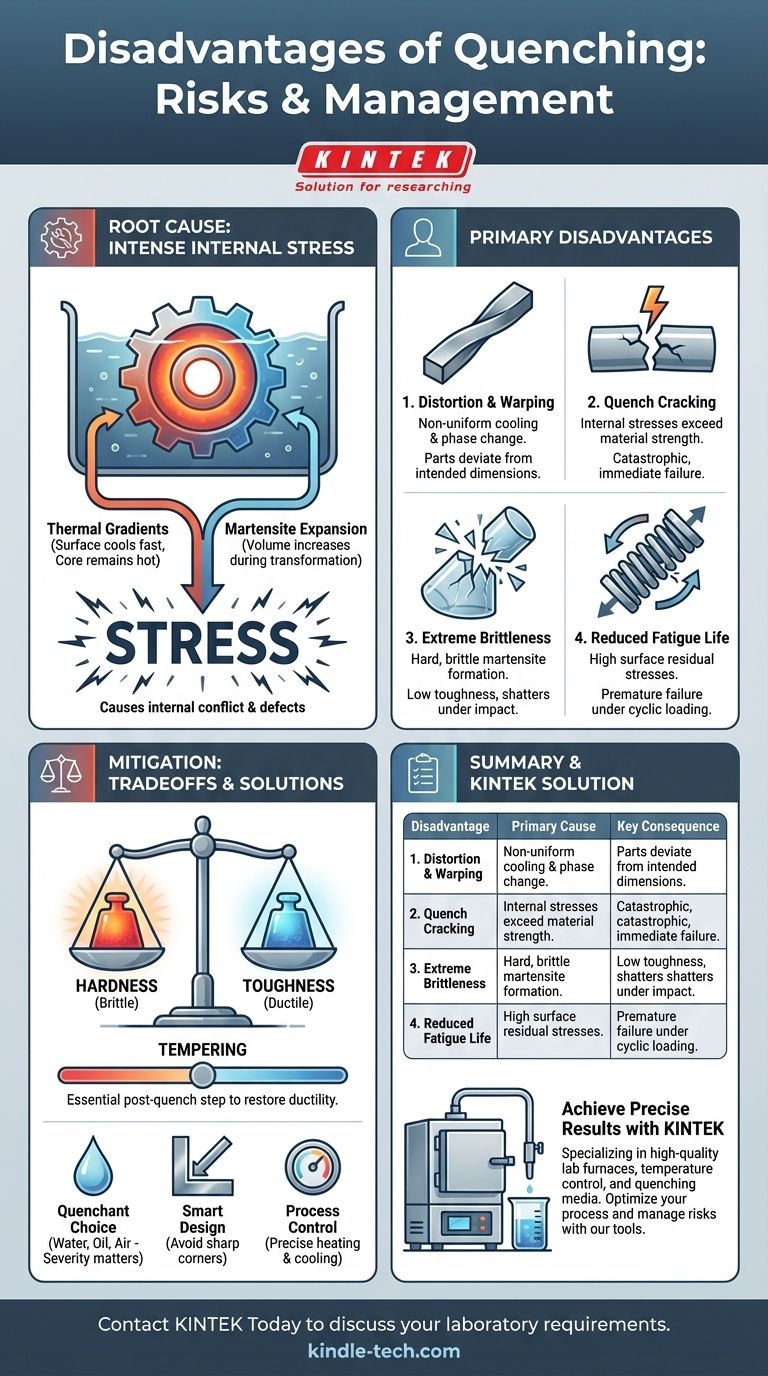

The Source of the Problem: Stress

The negative effects of quenching are not random; they are direct consequences of two physical events happening simultaneously: rapid cooling and phase transformation. Understanding this is key to mitigating the risks.

Thermal Gradients

When a hot part is submerged in a quenching medium, its surface cools almost instantly while its core remains hot. This temperature difference, or thermal gradient, causes the cooling, contracting surface to pull against the hot, expanded interior.

The Volume Change of Martensite

For steels, quenching is designed to force the high-temperature austenite phase to transform into martensite, a very hard and brittle crystal structure. Critically, this transformation involves a significant increase in volume.

The Result: Intense Internal Stress

These two factors combine to create a state of war within the material. The surface cools, contracts, and then suddenly expands as it forms martensite. All the while, the core is cooling more slowly. This non-uniform change in volume locks in massive amounts of residual stress, which is the root cause of nearly all quenching-related defects.

The Primary Disadvantages Explained

The internal stress generated during quenching manifests as several distinct and destructive problems.

Distortion and Warping

If the internal stresses exceed the material's elastic limit, they will physically deform the part. The component will no longer match its intended dimensions, a phenomenon known as distortion or warping. Long, thin sections are especially vulnerable.

Quench Cracking

This is the most catastrophic failure. If the internal stresses exceed the material's ultimate tensile strength, the part will simply crack. Cracks often initiate at sharp corners or holes, which act as stress concentrators. This can happen during the quench or even hours later as the stresses settle.

Extreme Brittleness

Martensite provides exceptional hardness and wear resistance, but it is inherently brittle. An "as-quenched" part has very low toughness and can shatter like glass under impact or shock loading. For this reason, a quenched part is almost never used without a subsequent heat treatment.

Reduced Fatigue Life

Even if a part does not visibly crack or warp, high levels of residual tensile stress on the surface can drastically reduce its fatigue life. These stresses act as a pre-load, making the part much more susceptible to failure from cyclic loading.

Understanding the Trade-offs and Mitigation

Quenching is a powerful tool, but it must be used with a clear understanding of its trade-offs. The goal is to achieve the desired hardness while minimizing the associated risks.

Hardness vs. Toughness

This is the fundamental compromise of heat treatment. Quenching pushes the material far to the hardness side of the spectrum at the direct expense of toughness. A harder part is more brittle.

The Critical Role of the Quenchant

The severity of the quench is determined by the cooling medium. Water provides a very fast, aggressive quench, creating high stress. Oil is slower and less severe. Air is the mildest. Choosing a quenchant that cools the part just fast enough to form martensite—and no faster—is crucial for minimizing distortion and cracking.

The Necessity of Tempering

A quenched part should be considered an incomplete product. A subsequent heating process called tempering is almost always required. Tempering relieves internal stresses and restores a controlled amount of toughness and ductility, making the material suitable for its intended service.

Geometry Matters

Good design is a key defense against quenching defects. Generous radii, uniform section thicknesses, and the elimination of sharp internal corners significantly reduce stress concentrations and make a part far less likely to crack.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

The decision to quench—and how to quench—depends entirely on the final application and performance requirements of the component.

- If your primary focus is maximum hardness and wear resistance: Quenching is necessary, but it must be followed by a tempering cycle to prevent catastrophic brittle failure.

- If your primary focus is toughness and impact resistance: A less severe quench (e.g., oil) followed by a higher-temperature temper is required, or an alternative heat treatment like normalizing may be more appropriate.

- If your primary focus is dimensional stability: Consider using an air-hardening steel that can be quenched slowly, or select a less aggressive quenchant to minimize the thermal shock that causes distortion.

By understanding these risks, you can transform quenching from a potential liability into a predictable and powerful manufacturing tool.

Summary Table:

| Disadvantage | Primary Cause | Key Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Distortion/Warping | Non-uniform cooling & phase transformation | Parts deviate from intended dimensions |

| Quench Cracking | Internal stresses exceed material strength | Catastrophic, often immediate part failure |

| Extreme Brittleness | Formation of hard, brittle martensite | Low toughness and impact resistance |

| Reduced Fatigue Life | High residual tensile stresses on the surface | Premature failure under cyclic loading |

Achieve precise and reliable heat treatment results with KINTEK.

Quenching is a delicate balance between achieving hardness and managing the risks of stress, distortion, and cracking. The right equipment and consumables are critical for control and repeatability.

KINTEK specializes in high-quality lab furnaces, temperature control systems, and quenching media tailored to your specific material and application needs. We help you mitigate the disadvantages of quenching by providing the tools for precise thermal processing.

Let our experts help you optimize your heat treatment process. Contact KINTEK today to discuss your laboratory's requirements for furnaces, quenchants, and consumables.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

- Graphite Vacuum Furnace High Thermal Conductivity Film Graphitization Furnace

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

People Also Ask

- Why is environmental control within a vacuum furnace important for diffusion bonding? Master Titanium Alloy Laminates

- How to vacuum out a furnace? A Step-by-Step Guide to Safe DIY Maintenance

- What is the maximum temperature in a vacuum furnace? It Depends on Your Materials and Process Needs

- What are the advantages of a vacuum furnace? Achieve Superior Purity and Control in Heat Treatment

- What is the structure of a vacuum furnace? A Guide to Its Core Components & Functions