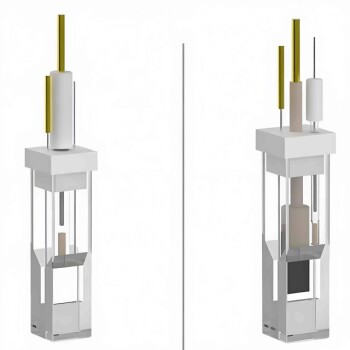

The primary function of a Gas Diffusion Electrode (GDE) in low-temperature carbon dioxide electrolysis is to drastically enhance the mass transfer of gaseous reactants to the reaction zone. By employing a porous structure, GDEs overcome the inherent physical limitation of low CO2 solubility in liquid electrolytes, enabling the high current densities required for industrial-scale production.

The core challenge in CO2 electrolysis is that carbon dioxide does not dissolve readily in water, starving the reaction of fuel. GDEs solve this by creating a direct bridge between the gas supply and the catalyst, removing the reliance on dissolved gas alone.

The Mechanism of Action

Creating a Three-Phase Boundary

Standard electrodes rely on two phases: the solid electrode and the liquid electrolyte. GDEs introduce a three-phase boundary where gas (CO2), liquid (electrolyte), and solid (catalyst) intersect simultaneously.

This intersection is critical because the electrochemical reaction can only occur where all three components meet. By maximizing this contact area, the electrode ensures the catalyst is fully utilized.

Overcoming Solubility Limitations

In traditional setups, the reaction rate is capped by how fast CO2 can dissolve and diffuse through the liquid to reach the electrode. This process is often too slow for practical applications.

GDEs bypass this bottleneck by delivering gaseous CO2 directly to the catalyst layer through porous channels. This allows the system to operate at reaction rates significantly higher than what simple diffusion through a liquid would permit.

Structural Composition and Stability

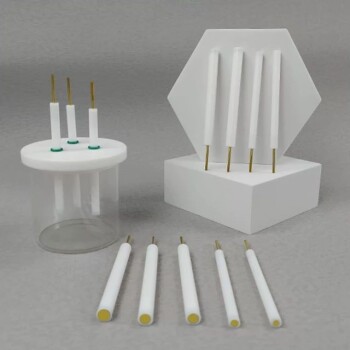

The Role of Porous Architecture

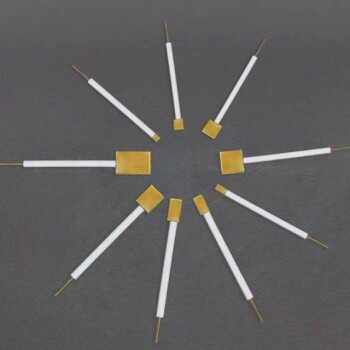

The physical structure of a GDE is designed to provide a massive internal surface area. This high surface area to volume ratio ensures that a large volume of reactant gas is constantly available at the reaction sites.

Hydrophobic Regulation with PTFE

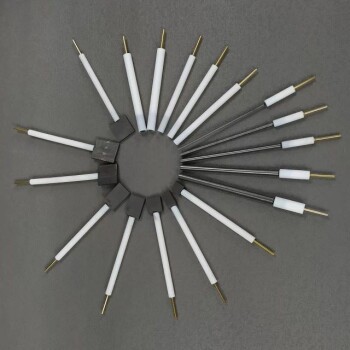

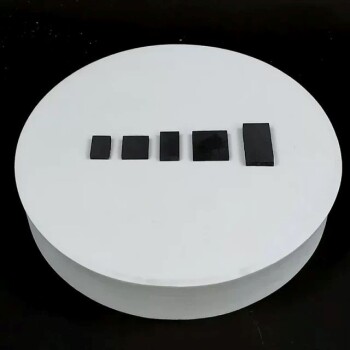

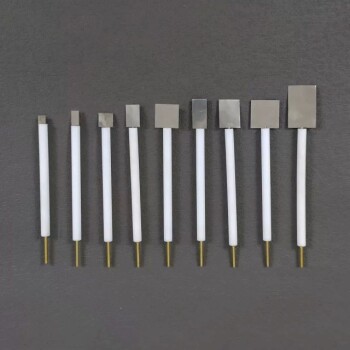

To function correctly, the electrode must breathe. Supplementary data indicates that Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) is commonly used as a binder to impart hydrophobic (water-repelling) properties to the electrode.

This hydrophobicity is essential for maintaining open pathways for gas flow. Without it, the liquid electrolyte would soak into the pores, blocking the CO2 from reaching the catalyst.

Understanding the Trade-offs

Managing Electrode Flooding

The most critical failure mode for GDEs is "flooding." This occurs when the balance of pressure or wettability shifts, causing the liquid electrolyte to penetrate the gas pores due to capillary action.

Once an electrode floods, the three-phase boundary is destroyed, reverting the system to a less efficient two-phase interface. This results in a sharp drop in performance and current density.

Balancing Conductivity and Hydrophobicity

Designing a GDE requires a delicate balance. You need enough PTFE to repel water and keep gas channels open, but not so much that it insulates the electrode or blocks the necessary ionic contact with the electrolyte.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

When selecting or designing GDEs for CO2 electrolysis, your focus should align with your specific operational constraints:

- If your primary focus is Industrial Scale-Up: Prioritize electrode structures that maximize the three-phase boundary area to support high current densities and rapid mass transfer.

- If your primary focus is Long-Term Stability: rigorous attention must be paid to the hydrophobic treatment (PTFE loading) to prevent pore wetting and electrode flooding over time.

By effectively bridging the gap between gaseous reactants and liquid electrolytes, GDEs transform CO2 electrolysis from a theoretical possibility into a viable industrial process.

Summary Table:

| Feature | Function in GDE | Benefit |

|---|---|---|

| Three-Phase Boundary | Intersects gas, liquid, and solid catalyst | Maximizes reaction sites and catalyst utilization |

| Porous Architecture | Direct delivery of gaseous CO2 | Overcomes low gas solubility in liquid electrolytes |

| PTFE Binder | Imparts hydrophobic (water-repelling) properties | Prevents electrode flooding and maintains gas pathways |

| High Surface Area | Increases contact volume | Supports industrial-scale current densities |

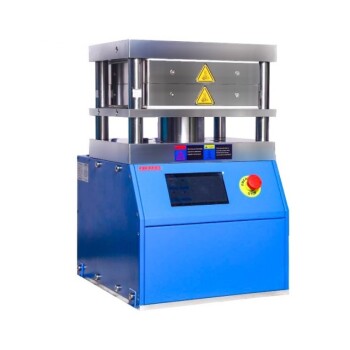

Maximize Your Electrochemical Efficiency with KINTEK

Ready to scale your CO2 electrolysis research? KINTEK provides high-performance electrolytic cells, electrodes, and specialized PTFE consumables designed to optimize mass transfer and prevent electrode flooding. Whether you are developing low-temperature carbon dioxide electrolysis processes or exploring advanced battery research, our comprehensive range of laboratory equipment and high-pressure reactors ensures precise results and long-term stability.

Enhance your lab's capabilities today—contact KINTEK to find the perfect solution for your application!

References

- Elias Klemm, K. Andreas Friedrich. <scp>CHEMampere</scp> : Technologies for sustainable chemical production with renewable electricity and <scp> CO <sub>2</sub> </scp> , <scp> N <sub>2</sub> </scp> , <scp> O <sub>2</sub> </scp> , and <scp> H <sub>2</sub> O </scp>. DOI: 10.1002/cjce.24397

This article is also based on technical information from Kintek Solution Knowledge Base .

Related Products

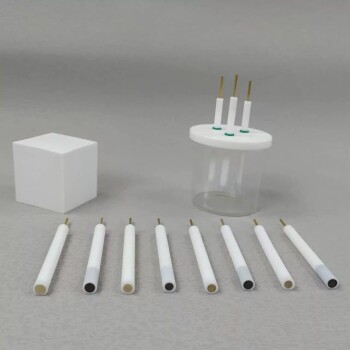

- Glassy Carbon Electrochemical Electrode

- Graphite Disc Rod and Sheet Electrode Electrochemical Graphite Electrode

- Glassy Carbon Sheet RVC for Electrochemical Experiments

- Reference Electrode Calomel Silver Chloride Mercury Sulfate for Laboratory Use

- RRDE rotating disk (ring disk) electrode / compatible with PINE, Japanese ALS, Swiss Metrohm glassy carbon platinum

People Also Ask

- How is a glassy carbon electrode activated before an experiment? Achieve Clean, Reproducible Electrochemical Data

- Why is glassy carbon selected for mediator-assisted indirect oxidation of glycerol? The Key to Unbiased Research

- How should a glassy carbon electrode be stored during long periods of non-use? Ensure Peak Performance & Longevity

- How to make a glassy carbon electrode? A Guide to the Industrial Pyrolysis Process

- What are the pre-treatment steps for a glassy carbon electrode before use? Ensure Reliable Electrochemical Data