We tend to view laboratory equipment as static tools. A beaker is a beaker. A scale is a scale.

But a tube furnace is different.

To the untrained eye, it appears to be a simple heating device. In reality, it is a complex negotiation between physics and chemistry.

It is not a generic piece of equipment; it is a purpose-built system. Every inch of its construction—from the density of the insulation to the transparency of the tube—is a direct response to a specific problem.

The design isn't about what the machine is. It is about what the machine must do.

Here is how the demands of your process shape the architecture of the furnace.

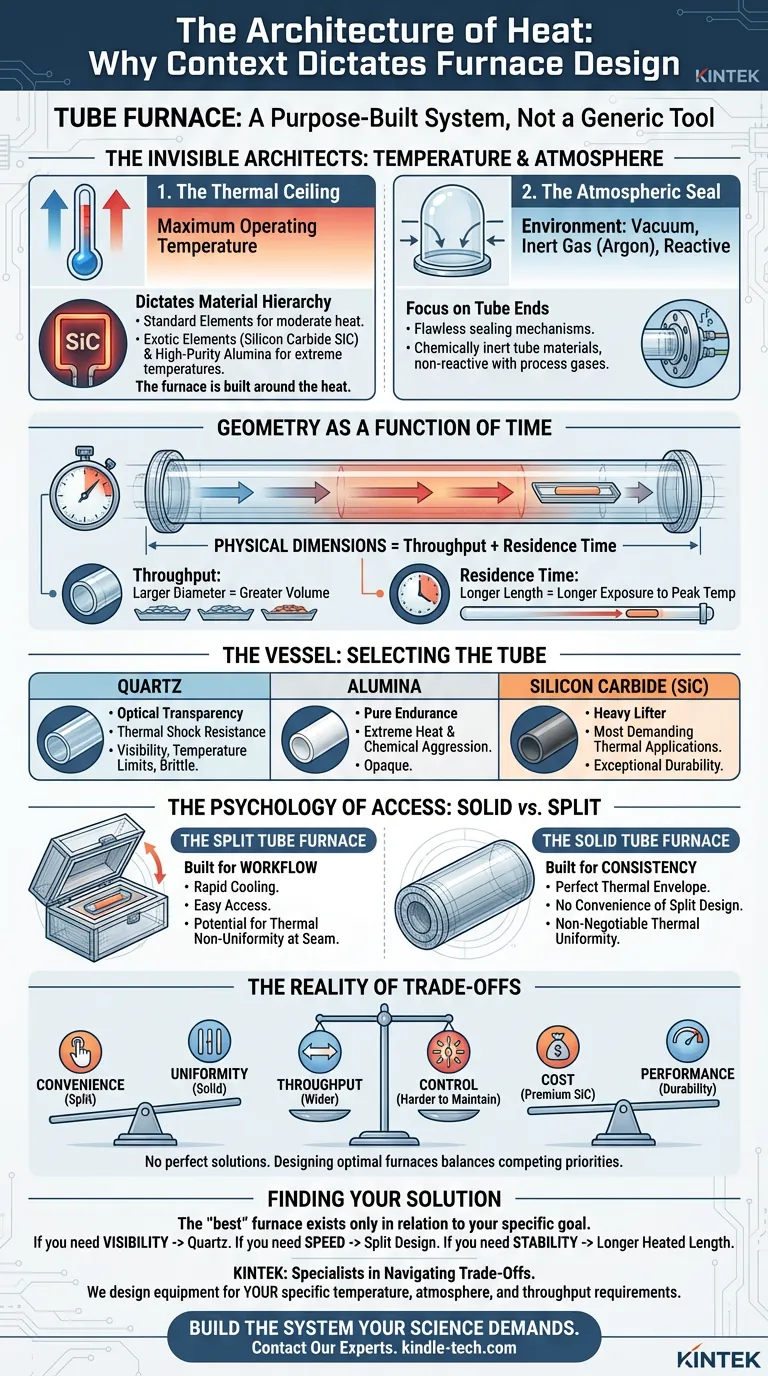

The Invisible Architects: Temperature and Atmosphere

Before an engineer draws a single line, they must ask the fundamental question: What is the environment?

The design of a tube furnace is determined entirely by its intended application. Two factors act as the primary constraints.

1. The Thermal Ceiling

The maximum operating temperature is the first filter. It dictates the hierarchy of materials.

If your process requires moderate heat, standard heating elements suffice. But as you push the boundaries of thermodynamics, the design must adapt. Extremely high temperatures force the use of exotic heating elements like Silicon Carbide (SiC) and robust tube materials like high-purity alumina.

The furnace is built around the heat, not the other way around.

2. The Atmospheric Seal

Heat is rarely the only variable. In advanced material science, the air itself is often the enemy.

Many processes require a vacuum, an inert gas like Argon, or a specific reactive environment. This requirement shifts the design focus to the ends of the tube.

The sealing mechanisms must be flawless. The tube material must be chemically inert, refusing to react with process gases even when pushed to thermal extremes.

Geometry as a Function of Time

Once the environment is defined, we look at the physics of flow.

The physical dimensions of the furnace tube—its length and diameter—are not arbitrary. They are mathematical calculations of throughput and residence time.

- Throughput: A larger diameter allows for a greater volume of material.

- Residence Time: The length of the tube determines how long the material is exposed to the peak temperature.

If you need a chemical reaction to complete fully, you cannot simply rush the material through. You need a longer heated zone. The tube’s length is essentially a physical representation of time.

The Vessel: Selecting the Tube

The tube is the heart of the system. It is the barrier between your sample and the heating elements.

Choosing the right material is a study in material properties:

- Quartz: Chosen for optical transparency and thermal shock resistance. It allows you to see the process, but it has temperature limits and is brittle.

- Alumina: Chosen for pure endurance. It survives where quartz fails, handling extreme heat and chemical aggression, but it is opaque.

- Silicon Carbide: The heavy lifter for the most demanding thermal applications.

The Psychology of Access: Solid vs. Split

Engineers must also consider the human element. How will the operator interact with the machine?

This leads to the choice between Solid and Split configurations.

The Split Tube Furnace

This design opens like a clamshell. It is built for workflow.

It allows for rapid cooling and easy access. If you are constantly changing samples or tweaking reactors, this design is superior. However, the seam between the halves introduces a minor variable: a potential point of thermal non-uniformity.

The Solid Tube Furnace

This is a continuous, single-piece chamber. It is built for consistency.

It lacks the convenience of the split design, but it offers a more perfect thermal envelope. It is the choice for processes where thermal uniformity is non-negotiable.

The Reality of Trade-offs

In engineering, as in life, there are no perfect solutions. There are only trade-offs.

Designing the optimal tube furnace requires balancing competing priorities.

| The Trade-Off | The Compromise |

|---|---|

| Convenience vs. Uniformity | Split furnaces offer ease of access; Solid furnaces offer better thermal consistency. |

| Throughput vs. Control | A wider tube processes more material but makes precise thermal uniformity harder to maintain. |

| Cost vs. Performance | Materials like SiC offer exceptional durability but come at a significant premium over standard options. |

Finding Your Solution

The "best" furnace does not exist in a vacuum. It exists only in relation to your specific goal.

- If you need visibility, you choose Quartz.

- If you need speed in sample changing, you choose a Split design.

- If you need stability over long durations, you choose a longer heated length.

At KINTEK, we understand that a tube furnace is not just a catalogue item. It is the engine of your research. We specialize in navigating these trade-offs to design equipment that fits your specific temperature, atmosphere, and throughput requirements.

Don't settle for a generic tool. Build the system your science demands.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube Laboratory Tubular Furnace

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

Related Articles

- Cracked Tubes, Contaminated Samples? Your Furnace Tube Is The Hidden Culprit

- Your Tube Furnace Is Not the Problem—Your Choice of It Is

- Why Your Ceramic Furnace Tubes Keep Cracking—And How to Choose the Right One

- The Physics of Patience: Why Your Tube Furnace Demands a Slow Hand

- Beyond the Spec Sheet: The Hidden Physics of a Tube Furnace's True Limit