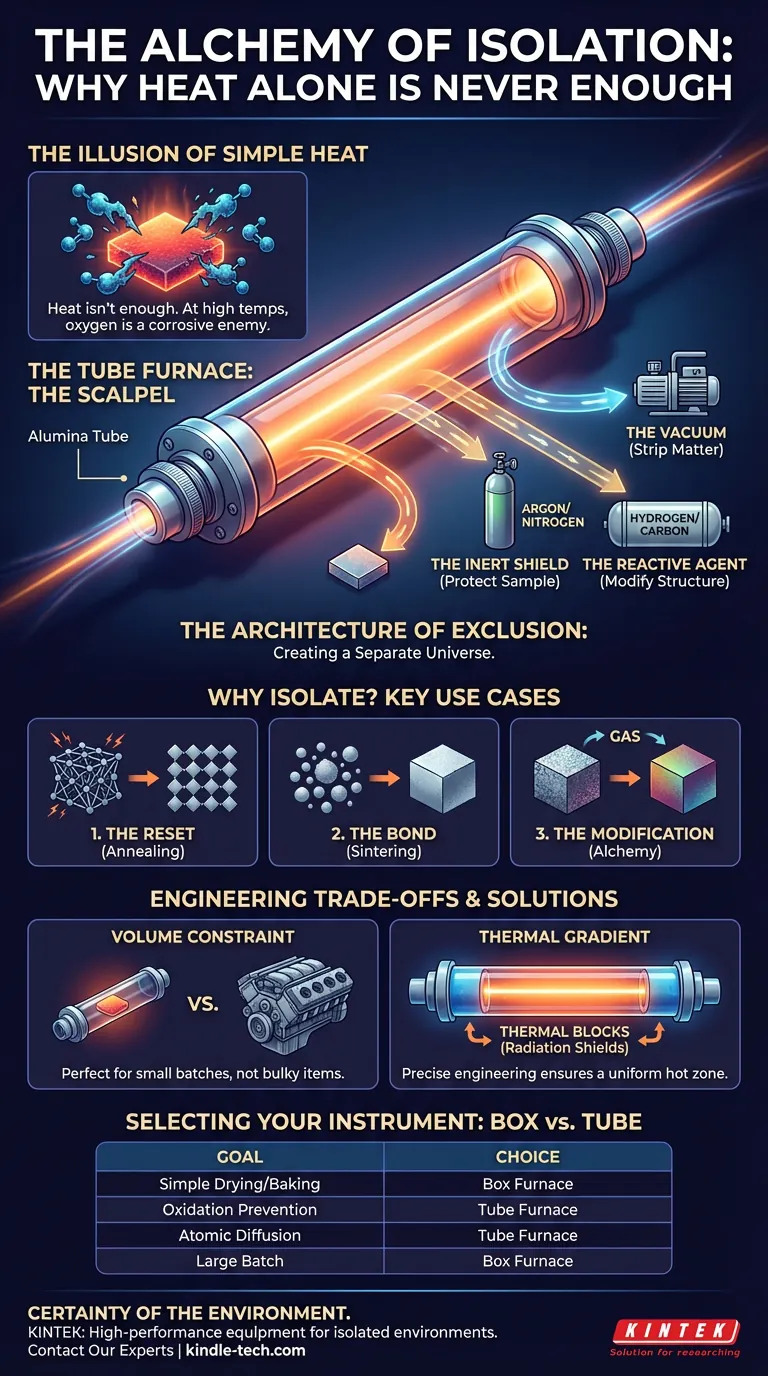

The Illusion of Simple Heat

In the history of innovation, we often mistake the visible variable for the only variable.

When we think of treating materials—making metals harder, ceramics stronger, or electronics more conductive—we instinctively think about heat. Fire is the oldest tool in humanity’s belt. We assume that if we just get the material hot enough, the physics will take care of itself.

But in modern materials science, heat is only half the equation.

The invisible enemy is the atmosphere. The air we breathe is chemically aggressive. At 1,000°C, oxygen isn't life-giving; it is a corrosive agent that destroys the atomic purity of a sample.

This is where the tube furnace enters the narrative. It is not merely an oven. It is a vessel designed to divorce a material from the chaotic environment of the outside world.

The Architecture of Exclusion

A standard box furnace is a hammer. It applies heat broadly.

A tube furnace is a scalpel.

Its anatomy is deceptively simple. A cylindrical tube—usually alumina or quartz—passes through a heating chamber. The genius lies not in the heating elements, but in the fittings at the ends of that tube.

By sealing the ends, the operator transforms the tube into a separate universe.

The Three States of Control

Once the tube is sealed, you gain the power of exclusion. You are no longer at the mercy of ambient air. You can choose one of three distinct paths:

- The Vacuum: Stripping away all matter to prevent reaction.

- The Inert Shield: Flowing Argon or Nitrogen to protect the sample without altering it.

- The Reactive Agent: Introducing Hydrogen or Carbon to intentionally modify the chemical structure.

The tube furnace is defined not by what it lets in, but by what it keeps out.

When to Isolate: The Use Cases

Why go through the complexity of gas lines and vacuum pumps? Because specific results require specific environments.

The applications of a tube furnace generally fall into three categories of increasing complexity.

1. The Reset (Annealing and Tempering)

Metals and semiconductors accumulate stress. They become brittle. Heating them is like hitting a reset button on their atomic structure.

However, doing this in air creates an oxide layer—a "skin" of rust or tarnish. A tube furnace allows for bright annealing in a reducing atmosphere, keeping the metal pure while relieving its internal stress.

2. The Bond (Sintering and Brazing)

Sintering turns powder into solids. Brazing joins two metals together.

Both processes rely on flow and diffusion. If oxygen is present, it forms barriers that prevent the particles from bonding or the filler metal from flowing. In a vacuum tube furnace, these barriers are removed. The materials merge seamlessly.

3. The Modification (Doping and Surface Treatment)

This is alchemy in its modern form. By introducing reactive gases, you change the nature of the material itself.

- Carburizing: Adding carbon to steel to make the surface diamond-hard.

- Nitriding: Diffusing nitrogen to resist wear.

The Engineering Trade-offs

Systemic complexity always comes with a cost. In the world of furnaces, there is no "perfect" tool, only the right tool for the constraints.

While the tube furnace offers superior control, it demands an understanding of its limitations.

The Volume Constraint The geometry is cylindrical. It is perfect for wafers, powders, and small batches. It is useless for large, bulky components. If you need to heat a car engine block, you use a box furnace. If you need to heat a few grams of experimental powder, you use a tube furnace.

The Thermal Gradient Physics dictates that the ends of the tube, where they stick out of the furnace, will be cooler. This creates a temperature gradient.

To combat this, precise engineering is required. We use thermal blocks (radiation shields) inside the tube to reflect heat back toward the center, creating a uniform "hot zone."

Selecting Your Instrument

The choice between a box furnace and a tube furnace is a choice between volume and precision.

Here is the decision matrix for the modern lab:

| If your goal is... | The logical choice is... | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Simple Drying or Baking | Box Furnace | Cost-effective; atmospheric control is unnecessary. |

| Oxidation Prevention | Tube Furnace | You must physically exclude oxygen to save the sample. |

| Atomic Diffusion | Tube Furnace | Requires a vacuum or reactive gas flow to drive the chemistry. |

| Large Batch Processing | Box Furnace | Geometry allows for stacking and bulkier items. |

The Certainty of the Environment

In the end, the quality of your output is determined by the purity of your inputs.

If you are pushing the boundaries of materials science, you cannot afford the randomness of ambient air. You need the certainty of a controlled environment.

At KINTEK, we understand that the furnace is the heart of the laboratory. We specialize in providing the high-performance equipment necessary to create these isolated environments. Whether you need high-vacuum capabilities or precise gas flow control, our engineers can help you configure the exact system your research demands.

Don't let the invisible variable ruin your results.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1200℃ Controlled Atmosphere Furnace Nitrogen Inert Atmosphere Furnace

- 1400℃ Controlled Atmosphere Furnace with Nitrogen and Inert Atmosphere

- Vacuum Sealed Continuous Working Rotary Tube Furnace Rotating Tube Furnace

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

- 1800℃ Muffle Oven Furnace for Laboratory

Related Articles

- Atmosphere Furnaces: Comprehensive Guide to Controlled Heat Treatment

- The Silent Saboteur in Your Furnace: Why Your Heat Treatment Fails and How to Fix It

- Muffle Furnace: Unraveling the Secrets of Uniform Heating and Controlled Atmosphere

- How Controlled Atmosphere Furnaces Improve Quality and Consistency in Heat Treatment

- Comprehensive Guide to Atmosphere Furnaces: Types, Applications, and Benefits