Imagine a materials scientist synthesizing a new catalyst. The precursor powders are pure, the gas flow is calibrated, yet the resulting material is inert. The experiment failed. The culprit isn't the chemistry; it's the furnace—a tool whose subtle design flaws created a thermal gradient just large enough to disrupt the crystal formation.

This scenario isn't an anomaly. It’s a common consequence of a fundamental misunderstanding. We tend to view a tube furnace as a generic utility, a simple box that gets hot. But in reality, a high-performance furnace is a purpose-built system. Every element of its design is a direct answer to the specific demands of the process it must serve.

The Illusion of the 'Standard' Furnace

There is no such thing as a "standard" tube furnace. There is only the right furnace for your application.

The temptation is to seek a one-size-fits-all solution. This psychological shortcut simplifies purchasing but complicates the science. The truth is that the furnace's design isn't just a feature set; it is the physical embodiment of your process requirements. Its form is forged by function.

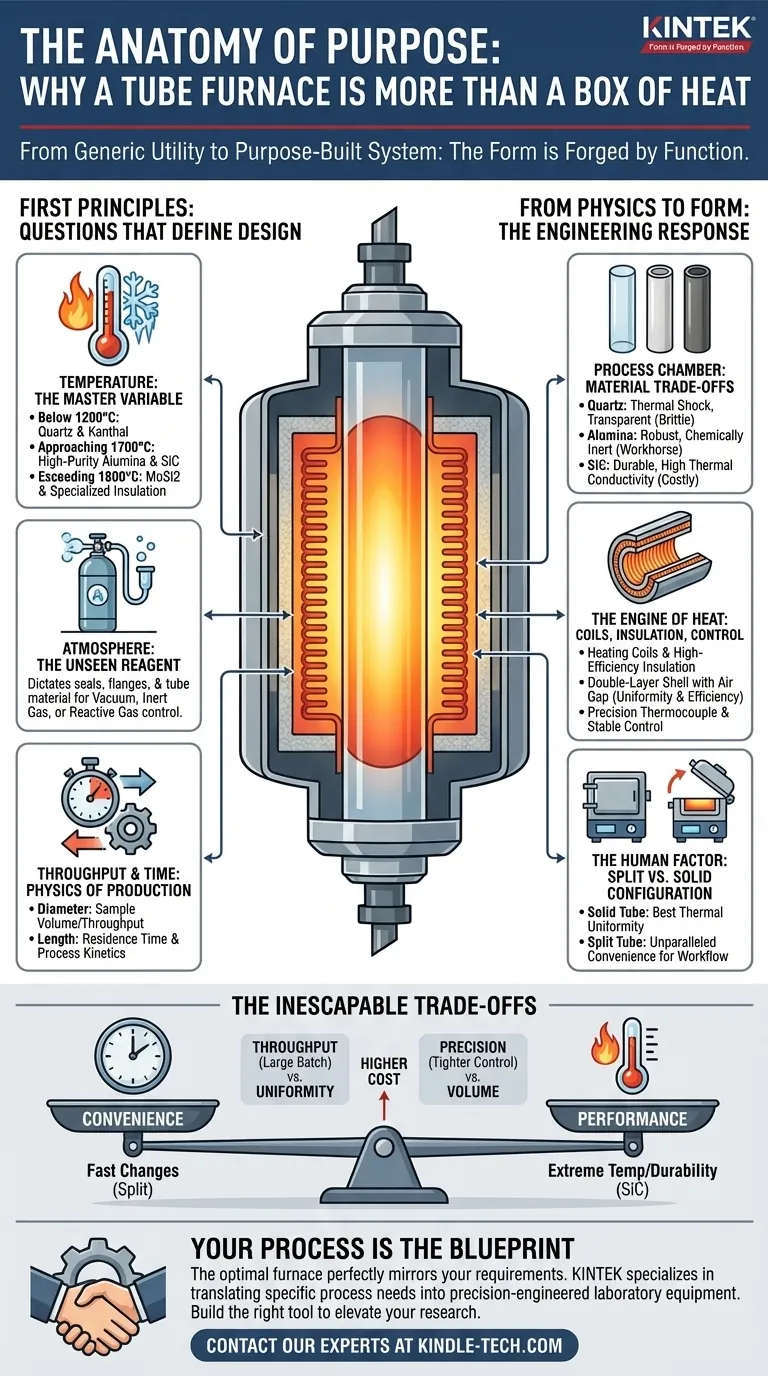

First Principles: The Questions That Define the Design

Before an engineer chooses a single screw or heating coil, they must deconstruct the user's process into a set of fundamental physical parameters. These are the "why" that dictates the "how."

Temperature: The Master Variable

The maximum required temperature is the most unforgiving constraint. It acts as a master variable, dictating nearly every other material choice in the system.

- Below 1200°C: Quartz tubes and Kanthal (FeCrAl) heating elements are often sufficient.

- Approaching 1700°C: High-purity alumina tubes and silicon carbide (SiC) elements become necessary.

- Exceeding 1800°C: Molybdenum disilicide (MoSi2) elements are required, alongside specialized insulation.

Temperature isn't just a number; it's a boundary condition that determines the very materials the furnace can be built from.

Atmosphere: The Unseen Reagent

The environment inside the tube is rarely just empty space. It is often an active component of the reaction, whether it's a high vacuum to prevent oxidation, an inert gas like argon to protect a sample, or a reactive gas to drive a chemical transformation.

This need for atmospheric control dictates the design of the seals and flanges. A system designed for a simple airflow is fundamentally different from one that must hold a hard vacuum at 1500°C. The tube material must also be non-reactive with the process gases at peak temperature.

Throughput and Time: The Physics of Production

The amount of material you need to process (throughput) and the duration it needs to be heated (residence time) define the furnace's geometry.

- Diameter: A wider tube accommodates a larger sample volume or a higher throughput for continuous processes.

- Length: A longer heated zone increases the residence time, ensuring that the material is exposed to the target temperature long enough for the desired reaction or phase change to complete.

These dimensions are a direct translation of your process's scale and kinetics into physical steel, ceramic, and wire.

From Physics to Form: The Engineering Response

Once the core requirements are defined, engineers select and assemble the components. Each choice is a deliberate step in building a system optimized for a single purpose.

The Process Chamber: More Than Just a Tube

The tube is the heart of the furnace. Its material and dimensions are a critical trade-off.

- Quartz: Offers excellent thermal shock resistance and is transparent, making it ideal for processes that require visual monitoring, like crystal growth. It is, however, brittle.

- Alumina: A robust and versatile ceramic, it is the workhorse for a wide range of high-temperature applications requiring chemical inertness.

- Silicon Carbide (SiC): Provides exceptional durability and thermal conductivity but comes at a higher cost.

The Engine of Heat: Coils, Insulation, and Control

Heating coils, typically wrapped around the ceramic tube, are the furnace's engine. They are embedded in a high-efficiency insulating matrix to minimize heat loss and ensure the outer shell remains cool to the touch.

Modern designs, like those specialized by KINTEK, often feature a double-layer shell with an air gap. This not only improves energy efficiency but also creates a more uniform temperature field inside the tube—a critical factor for repeatable results. A precisely placed thermocouple provides the feedback that allows the control system to maintain temperature with incredible stability.

The Human Factor: Split vs. Solid Configuration

The physical layout of the furnace is a direct reflection of the lab's workflow.

- Solid Tube Furnace: A single-piece chamber offers the best possible thermal uniformity.

- Split Tube Furnace: Hinged into two halves, this design allows the chamber to be opened. This provides unparalleled convenience for loading and unloading intact sample holders or reactors, drastically improving workflow efficiency for processes requiring frequent access.

This choice is a classic engineering trade-off: do you prioritize absolute thermal perfection or operational speed and convenience?

The Inescapable Trade-offs

Selecting a furnace means navigating a series of balanced compromises. Understanding these trade-offs is key to making an informed decision.

| Priority | You Gain | You Compromise |

|---|---|---|

| Convenience | Fast sample changes (Split Tube) | Potential for minor thermal non-uniformity |

| Performance | Extreme temperature, durability (SiC) | Higher initial cost |

| Throughput | Large batch sizes (Wider/Longer Tube) | Challenges in perfect temperature uniformity |

| Precision | Tighter thermal control (Smaller Tube) | Limited sample volume |

Your Process is the Blueprint

Ultimately, the optimal furnace is not the one with the highest temperature rating or the most features. It is the one whose design parameters perfectly mirror the requirements of your work.

- For high-temperature stability in inert atmospheres, an alumina tube furnace is your blueprint.

- For processes demanding visual observation, a system built around a quartz tube is the correct architecture.

- For a high-throughput lab with frequent sample changes, the ergonomic advantages of a split-tube furnace provide the most value.

Understanding your process is the first and most critical step. At KINTEK, we specialize in translating those specific process needs into reliable, precision-engineered laboratory equipment. We help you navigate the trade-offs to build the tool that doesn't just do the job, but elevates your research.

If your work demands more than just a box of heat, let's build the right furnace for your purpose. Contact Our Experts

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube Laboratory Tubular Furnace

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

Related Articles

- Installation of Tube Furnace Fitting Tee

- Why Your Furnace Components Keep Failing—And the Material Science Fix

- Entropy and the Alumina Tube: The Art of Precision Maintenance

- Cracked Tubes, Contaminated Samples? Your Furnace Tube Is The Hidden Culprit

- Your Tube Furnace Is Not the Problem—Your Choice of It Is