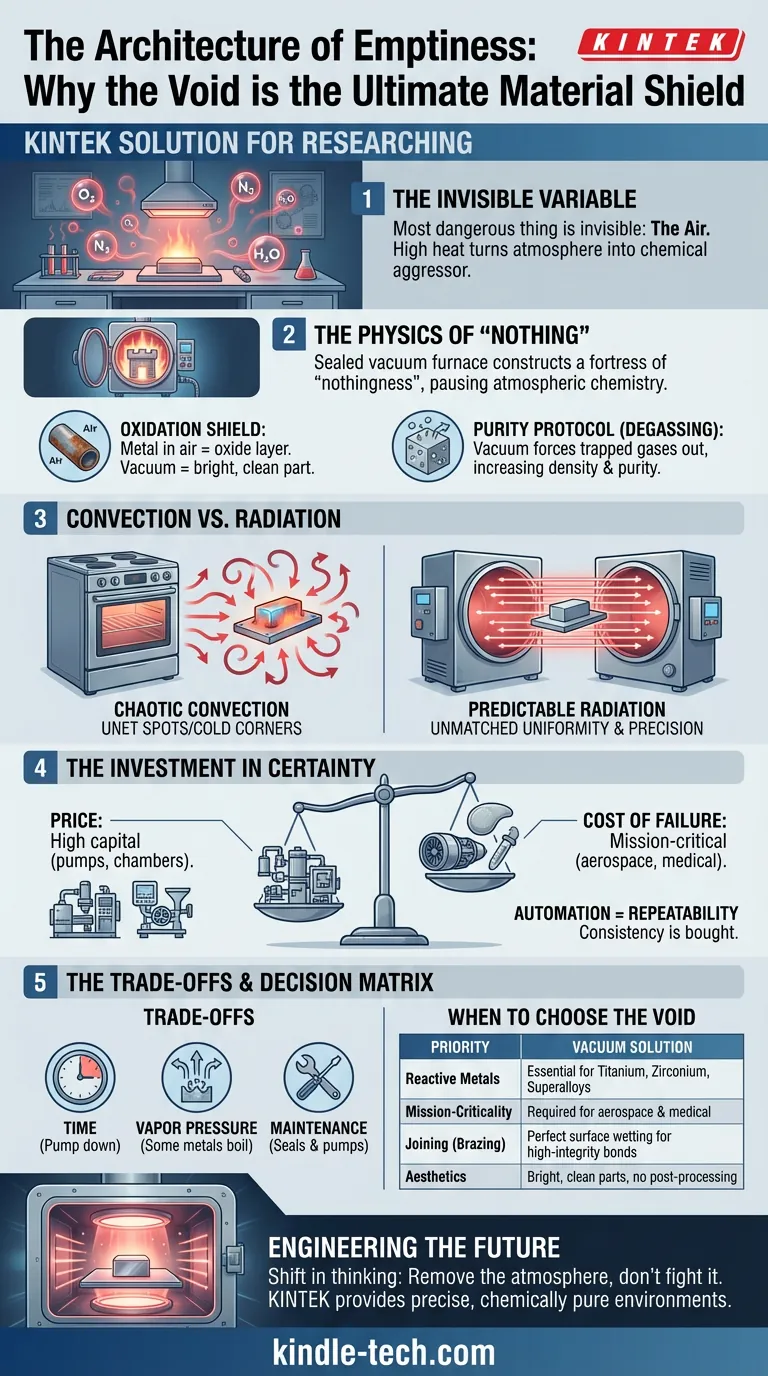

The Invisible Variable

The most dangerous thing in your laboratory is invisible.

It surrounds your workbench, flows over your samples, and settles into the microscopic pores of your materials. It is the air itself.

In standard conditions, air is benign. But introduce high heat—the kind required for sintering, brazing, or heat treating—and the atmosphere becomes a chemical aggressor. Oxygen seeks to corrode. Nitrogen alters surface hardness. Water vapor introduces hydrogen embrittlement.

Material science is often a battle against these variables. The goal is to isolate the variables you can control from the chaos you cannot.

This is the engineering romance of the sealed vacuum furnace. It is not merely a machine that gets hot; it is a machine that constructs a fortress of "nothingness." Inside this void, we pause the laws of atmospheric chemistry, allowing materials to become their best selves without interference.

The Physics of "Nothing"

The fundamental advantage of a vacuum furnace is the removal of the atmosphere. But to understand the value, you have to understand the threat.

Normal air contains 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen. At 1,000°C, these are not passive gases. They are reactants.

The Shield Against Oxidation

When you heat metal in air, it creates an oxide layer—a brittle, discolored skin that ruins conductivity and structural integrity.

A vacuum furnace removes the oxygen. The result is a part that emerges bright, clean, and chemically unaltered. It requires no acid baths, no sandblasting, and no secondary scrubbing.

The Purity Protocol (Degassing)

The vacuum does not just protect the outside of the material; it cleans the inside.

Metals often trap volatile gases and impurities within their crystalline structure. Under the extreme low pressure of a vacuum furnace, these trapped gases are forced out—a process called degassing.

The result is a material with higher density and superior purity than when it entered the chamber.

Convection vs. Radiation: The Geometry of Heat

In a standard oven, heat moves via convection. Air currents swirl around the part. This is chaotic. It relies on the flow of gas, which naturally creates hot spots and cold corners.

A vacuum has no air to move heat. Therefore, it relies on radiation.

Radiant heat travels in straight lines, like light. It is geometric and predictable. This allows for:

- Unmatched Uniformity: The temperature difference across a workload can be maintained within a few degrees.

- Precision: Regardless of the shape of the component, the heat transfer is governed by physics, not airflow.

The Investment in Certainty

In engineering, there is a difference between "price" and "cost."

The price of a vacuum furnace is high. It requires complex pumps, double-walled water-cooled chambers, and sophisticated seals. It is a heavy capital investment compared to an atmospheric box furnace.

But the cost of failure in mission-critical applications is higher.

If you are manufacturing aerospace turbine blades, medical implants, or semiconductors, you cannot afford "mostly good." You need absolute repeatability.

Automation as a Standard

Modern vacuum furnaces remove the human element. The cycle—pump down, ramp up, soak, and quench—is executed by a computer.

This guarantees that the batch you run today is metallurgically identical to the batch you ran six months ago. You are buying consistency.

The Trade-offs

A vacuum furnace is a specialized tool, not a universal hammer. It demands respect for its limitations:

- Time: Creating a vacuum takes time. The "pump down" cycle adds minutes or hours to the process.

- Vapor Pressure: Some metals, like zinc or magnesium, have high vapor pressures. In a deep vacuum, they don't just melt; they boil away and vanish.

- Maintenance: A vacuum leak is a process failure. Seals and pumps require diligent care.

Decision Matrix: When to Choose the Void

You do not need a vacuum furnace to bake clay. You need it when the margin for error is zero.

| If your priority is... | The Vacuum Solution |

|---|---|

| Reactive Metals | Essential for Titanium, Zirconium, and Superalloys that die in oxygen. |

| Mission-Criticality | Required for aerospace and medical parts where fatigue life is paramount. |

| Joining (Brazing) | Creates perfect surface wetting for high-integrity bonds. |

| Aesthetics | Delivers bright, clean parts requiring no post-processing. |

Engineering the Future

The vacuum furnace represents a shift in thinking. We stop trying to fight the atmosphere with fluxes and cover gases, and instead, we simply remove it.

At KINTEK, we understand that for high-stakes research and production, control is everything. Our equipment provides the precise, chemically pure environments necessary to push materials to their theoretical limits.

It is an investment in certainty.

Ready to master your material environment? Contact Our Experts to discuss how KINTEK vacuum solutions can bring precision to your laboratory.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Small Vacuum Heat Treat and Tungsten Wire Sintering Furnace

- Graphite Vacuum Furnace IGBT Experimental Graphitization Furnace

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Graphite Vacuum Furnace High Thermal Conductivity Film Graphitization Furnace

Related Articles

- Mastering Vacuum Furnace Brazing: Techniques, Applications, and Advantages

- Exploring the Advanced Capabilities of Spark Plasma Sintering (SPS) Furnaces

- Exploring Tungsten Vacuum Furnaces: Operation, Applications, and Advantages

- Vacuum Induction Furnace Fault Inspection: Essential Procedures and Solutions

- Unlocking the Potential: Vacuum Levitation Induction Melting Furnace Explained