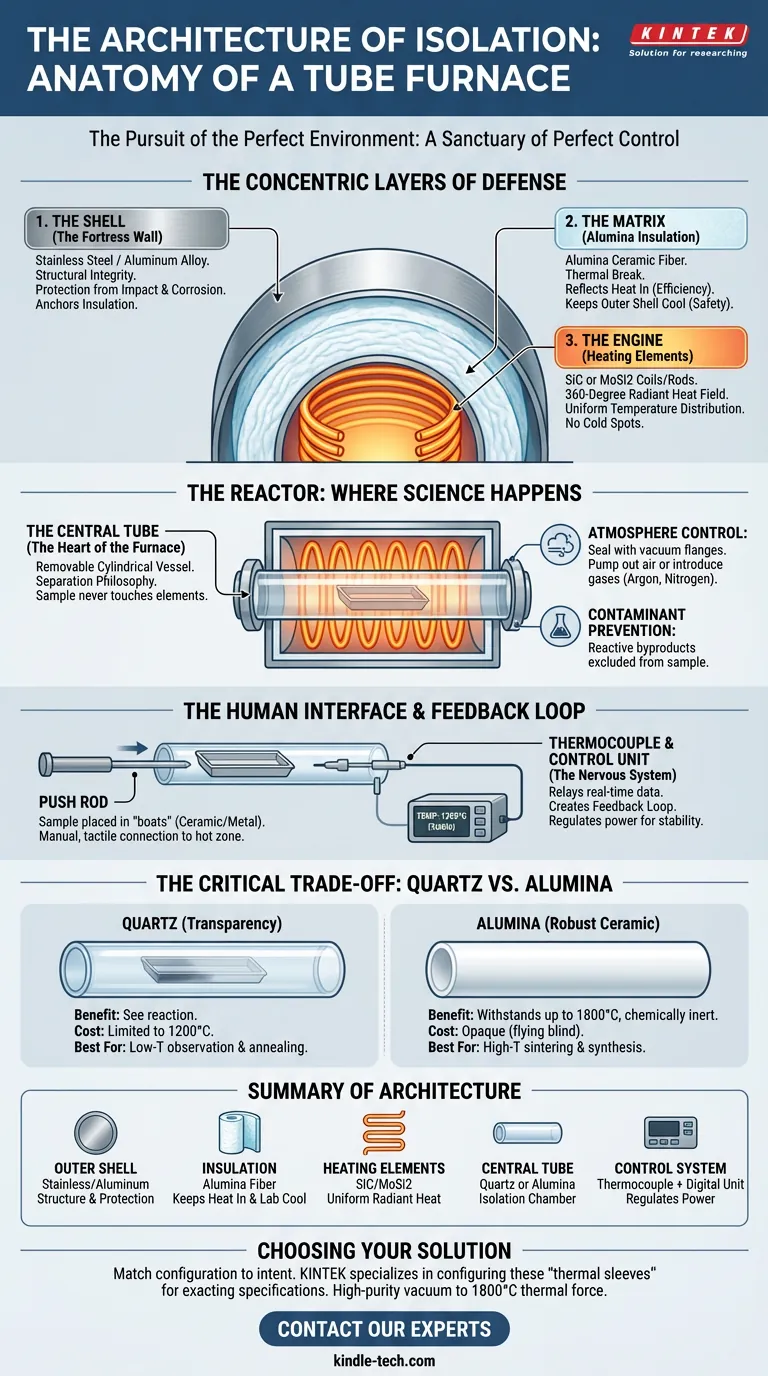

The Pursuit of the Perfect Environment

In scientific experimentation, chaos is the enemy.

The world is full of variables—fluctuating temperatures, rogue air currents, and contaminants. To understand how a material behaves, you must first exclude the world. You need a sanctuary of perfect control.

The tube furnace is that sanctuary.

At first glance, it appears to be a simple heating device. But to the engineering eye, it is a sophisticated "thermal sleeve." Its physical description is not just a list of parts; it is a study in concentric layers, each designed to isolate a sample in a central, stable zone.

Here is how that architecture works, from the protective shell to the reactive core.

The Concentric Layers of Defense

A tube furnace is built like a fortress. It consists of layers designed to keep the extreme heat in and the chaotic environment out.

1. The Shell: The Fortress Wall

The outermost layer is the barrier between the laboratory and the reactor.

Typically constructed from heavy-duty stainless steel or aluminum alloy, this casing provides structural integrity. It is the chassis upon which the instrument is built.

Its primary role is protection. It shields internal components from impact and corrosion while anchoring the heavy insulation within.

2. The Matrix: Alumina Insulation

Inside the shell lies the thermal break.

This is usually a thick layer of alumina ceramic fiber. In high-temperature engineering, insulation is not passive; it is an active safety feature.

It performs a dual function:

- Efficiency: It reflects heat back toward the center, minimizing energy loss.

- Safety: It ensures that while the core reaches 1700°C, the outer shell remains cool enough to touch.

3. The Engine: Heating Elements

Buried within the insulation are the muscles of the machine.

These are high-resistance coils or rods—often made of Silicon Carbide (SiC) or Silicon Molybdenum (MoSi2). Unlike a hotplate that heats from the bottom, these elements encircle the central cavity.

They create a 360-degree radiant heat field, ensuring that temperature distribution is perfectly uniform. There are no cold spots in this tunnel.

The Reactor: Where Science Happens

The previous layers exist to support one component: The Central Tube.

This is the heart of the furnace. It is a removable, cylindrical vessel that runs through the center of the heating zone. Its design represents a critical engineering philosophy: Separation.

The sample never touches the heating elements. It sits inside the tube.

This physical separation allows for two distinct capabilities:

- Atmosphere Control: By sealing the ends of the tube with vacuum flanges, you can pump out air or introduce gases like argon or nitrogen.

- Contaminant Prevention: Reactive byproducts from the heating elements cannot reach the sample.

The Human Interface

How do we interact with this hostile environment? We don't touch it directly.

Samples are placed in "boats"—trays made of ceramic or metal. Using a push rod, operators slide these boats into the "hot zone." It is a manual, tactile connection to a digital, high-heat process.

The Feedback Loop

A heating system without eyes is a runaway train.

To maintain precision, a thermocouple acts as the nervous system. Placed against the central tube, this sensor relays real-time data to a digital control unit.

This creates a feedback loop. If the temperature drops 1°C, the controller pulses power to the elements. If it overshoots, power is cut. This constant conversation ensures the environment remains stable.

The Critical Trade-off: Quartz vs. Alumina

The physical limits of the furnace are dictated by the material of the central tube. Engineers must choose between visibility and endurance.

The Case for Quartz

Quartz tubes offer transparency.

- The Benefit: You can see the reaction as it happens.

- The Cost: It is generally limited to 1200°C.

- Best For: Low-temperature observation and annealing.

The Case for Alumina

Alumina is a robust ceramic.

- The Benefit: It withstands brutal heat, up to 1800°C. It is chemically inert.

- The Cost: It is opaque. You are flying blind.

- Best For: High-temperature sintering and synthesis.

Summary of Architecture

| Component | Material & Function |

|---|---|

| Outer Shell | Stainless steel/Aluminum. Provides structure and protection. |

| Insulation | Alumina ceramic fiber. Keeps heat in and the lab cool. |

| Heating Elements | SiC/MoSi2 coils. Generates uniform, radiant heat. |

| Central Tube | Quartz (Transparent) or Alumina (High Heat). The isolation chamber. |

| Control System | Thermocouple + Digital Unit. The brain that regulates power. |

Choosing Your Solution

The tube furnace is a versatile tool, but its configuration must match your intent.

If you need to witness physical changes at lower temperatures, the transparency of quartz is essential. If your work involves pushing materials to their thermal limits in aggressive atmospheres, the resilience of alumina is non-negotiable.

At KINTEK, we understand that you aren't just buying a furnace; you are building a controlled environment for your research. We specialize in configuring these "thermal sleeves" to meet exacting specifications.

Whether you require the high-purity isolation of a vacuum system or the brute thermal force of an 1800°C reactor, we can help you architect the perfect solution.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube Laboratory Tubular Furnace

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

Related Articles

- High Pressure Tube Furnace: Applications, Safety, and Maintenance

- Installation of Tube Furnace Fitting Tee

- The Anatomy of Control: Why Every Component in a Tube Furnace Matters

- Beyond the Spec Sheet: The Hidden Physics of a Tube Furnace's True Limit

- Your Tube Furnace Is Not the Problem—Your Choice of It Is