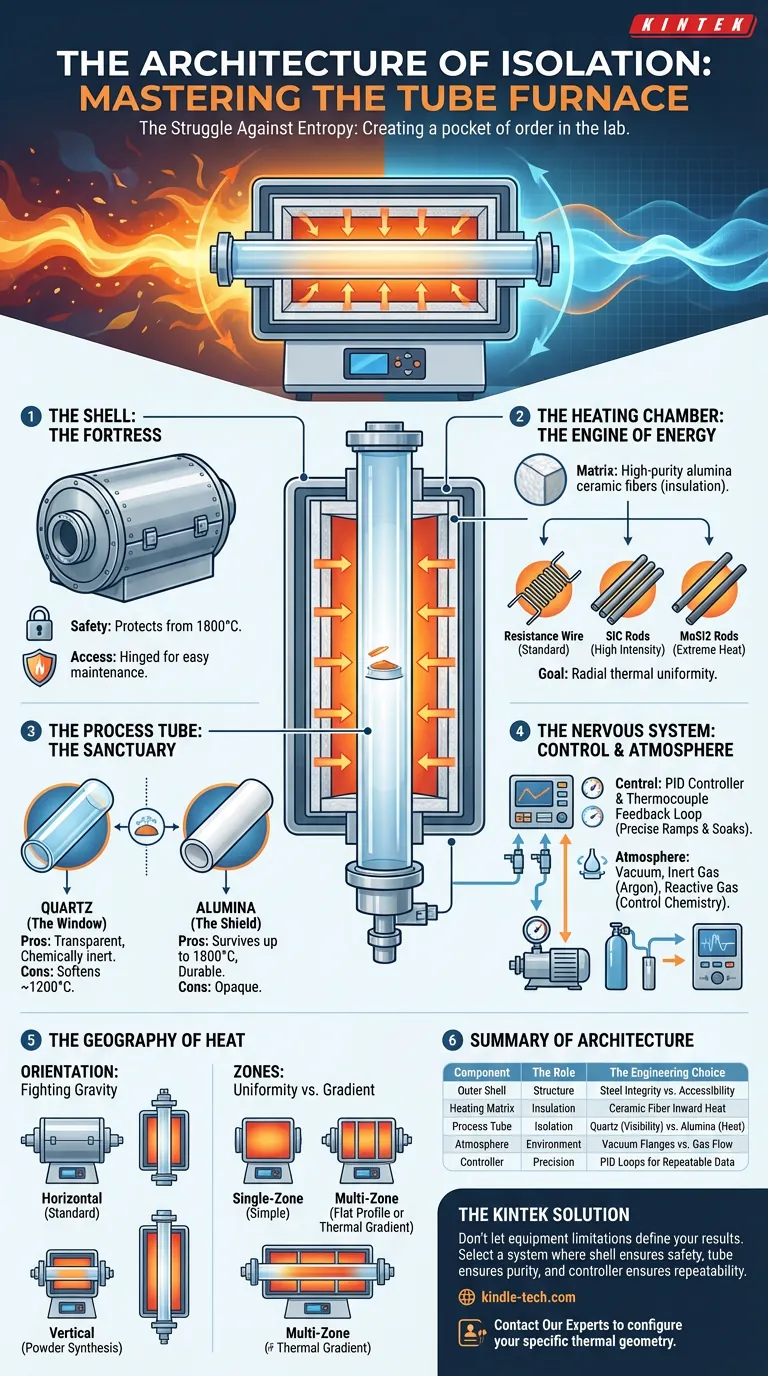

The Struggle Against Entropy

In the laboratory, the universe is your adversary. The laws of thermodynamics drive everything toward equilibrium—cooling down, oxidizing, and mixing with the ambient chaos.

Your job as a researcher is to create a pocket of order. You need a specific temperature, a specific atmosphere, and total isolation.

A tube furnace is not merely an oven; it is a modular defense against entropy.

Its structure is designed for a singular, paradoxical purpose: to subject a sample to extreme violence (high heat) while protecting it with extreme gentleness (atmospheric isolation). Understanding this anatomy is not just about maintenance; it is about understanding the limits of your experiment.

Here is the engineering logic behind the machine.

The Shell: The Fortress

The furnace begins with the outer shell. In cheaper systems, this is just a box. In high-precision engineering, it is a structural guarantee.

Constructed from heavy-duty steel or aluminum alloys, the shell performs two silent duties:

- Safety: It keeps the 1800°C interior from melting the lab bench (or the researcher).

- Access: Hinged designs allow the heating chamber to open, revealing the process tube without dismantling the setup.

The Heating Chamber: The Engine of Energy

Inside the shell lies the heart: the heating chamber.

This is usually a matrix of high-purity alumina ceramic fibers. It is lightweight but acts as a formidable thermal barrier. Embedded within this matrix are the heating elements—the "muscles" of the system.

Depending on your target temperature, these elements vary:

- Resistance Wire: The standard workhorse.

- Silicon Carbide (SiC) Rods: For higher intensity.

- Silicon Molybdenum (MoSi2) Rods: For extreme heat capability.

The engineering goal here is radial distribution. The heat must be directed inward, creating a cylinder of thermal uniformity. If the distribution is off, your data is noise.

The Process Tube: The Sanctuary

This is where the magic—and the anxiety—happens.

The process tube runs through the center of the heating chamber. It is the only component that touches your sample. It physically isolates the reaction from the heating elements and the outside world.

Choosing the material for this tube is a psychological trade-off between visibility and endurance:

Quartz (The Window)

- Pros: Transparent. You can watch the reaction occur. Chemically inert for CVD.

- Cons: Softens around 1200°C.

- The Vibe: Great for lower-temperature precision where visual confirmation matters.

Alumina (The Shield)

- Pros: Survives up to 1800°C. Extremely durable.

- Cons: Opaque. You are flying blind.

- The Vibe: Essential for high-temperature sintering or annealing where heat resistance is the only metric that counts.

The Nervous System: Control and Atmosphere

A furnace without a brain is just a fire hazard.

The Control System relies on a feedback loop. A thermocouple extends into the hot zone, sensing reality. A digital PID controller compares that reality to your setpoint and adjusts the power. This allows for precise ramps (heating up) and soaks (staying put).

But the true power of a tube furnace lies in the Atmosphere System.

By attaching vacuum pumps or gas supplies to the tube's flanges, you transform the device. It stops being a heater and becomes a reactor. You can purge oxygen, introduce argon, or create a vacuum. You control the chemistry as much as the physics.

The Geography of Heat

When configuring a furnace, you are designing the environment your sample will inhabit. There are three main variables to consider.

1. Orientation: Fighting Gravity

- Horizontal: The standard. Easy to load.

- Vertical: Uses gravity to your advantage. Ideal for powder synthesis or minimizing contact between the sample and the tube walls.

2. Zones: Uniformity vs. Gradient

- Single-Zone: The furnace has one thermostat. Simple, effective.

- Multi-Zone: The furnace has multiple, independent heating sections. This allows you to create a perfectly flat temperature profile over a long distance, or a specific thermal gradient (hot at one end, cool at the other) to drive condensation.

Summary of Architecture

| Component | The Role | The Engineering Choice |

|---|---|---|

| Outer Shell | Structure | Steel integrity vs. accessibility. |

| Heating Matrix | Insulation | Ceramic fiber to direct heat inward. |

| Process Tube | Isolation | Quartz for visibility vs. Alumina for heat. |

| Atmosphere | Environment | Vacuum flanges for purity vs. Gas flow for reaction. |

| Controller | Precision | PID loops for repeatable data. |

The KINTEK Solution

Science is hard enough without fighting your equipment.

When you select a tube furnace, you are choosing the constraints of your future experiments. You need a system where the "shell" ensures safety, the "tube" ensures purity, and the "controller" ensures repeatability.

KINTEK understands the romance of this engineering. We specialize in lab equipment and consumables designed for the rigors of modern research. Whether you need the transparency of a quartz CVD system or the brute force of a high-temperature alumina sintering furnace, we provide the modular architectures to make it happen.

Don't let equipment limitations define your results.

Contact Our Experts to configure a furnace that fits your specific thermal geometry.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube Laboratory Tubular Furnace

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

Related Articles

- Your Tube Furnace Is Not the Problem—Your Choice of It Is

- High Pressure Tube Furnace: Applications, Safety, and Maintenance

- The Physics of Patience: Why Your Tube Furnace Demands a Slow Hand

- Installation of Tube Furnace Fitting Tee

- Mastering the Micro-Environment: Why the Tube Furnace Is a Scientist's Most Powerful Tool for Innovation