There is a seduction in the specification sheet.

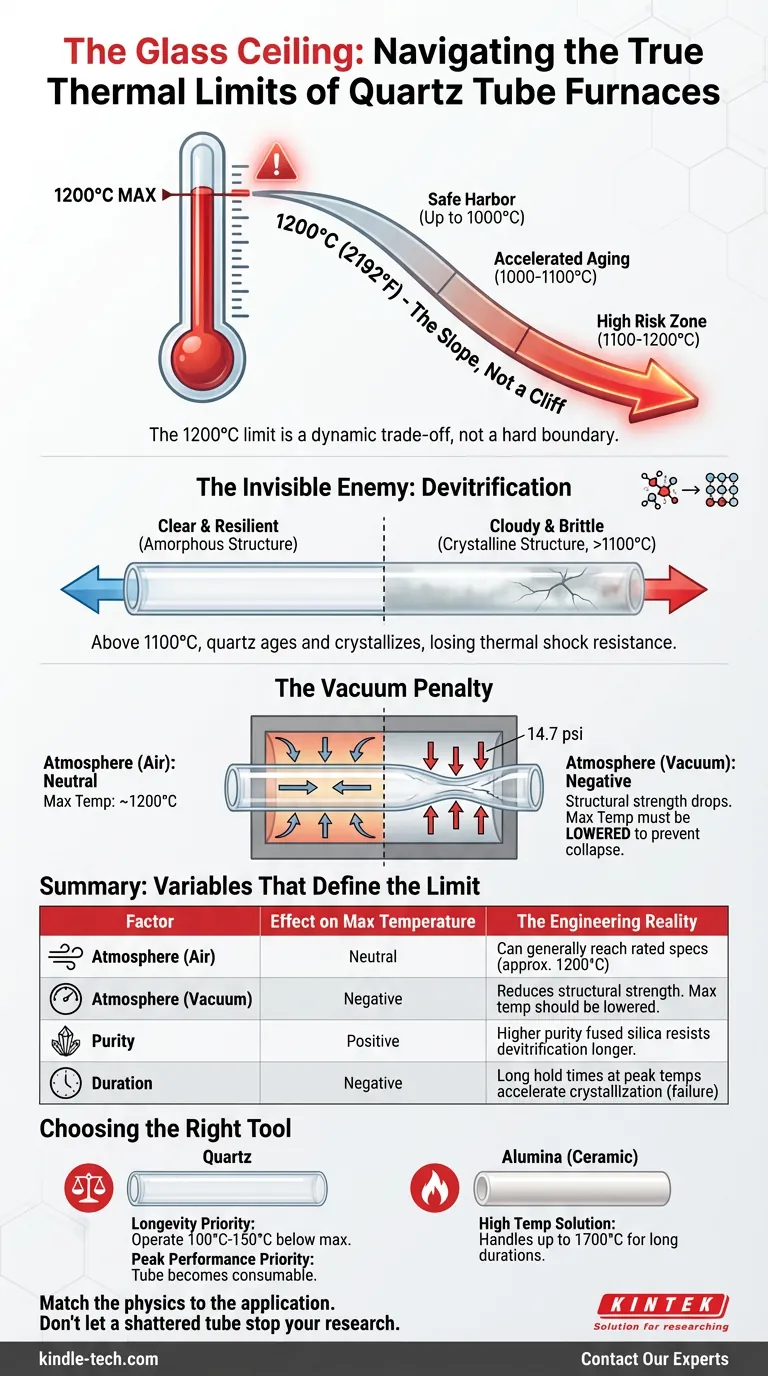

When you look at the manual for a quartz tube furnace, you will likely see a bold number: 1200°C (2192°F).

Engineers and lab managers often treat this number as a hard boundary—a safe harbor up to the very last degree. They assume that if the dial reads 1190°C, safety is guaranteed.

But materials science is rarely that binary.

The reality of high-temperature processing is that the 1200°C limit is not a cliff; it is a slope. It is a dynamic trade-off between your processing goals, the atmospheric pressure inside the tube, and how often you are willing to replace your equipment.

Here is the engineering reality behind the "Glass Ceiling" of quartz.

The Romance of Fused Silica

To understand the limit, you must understand the material.

The "quartz" used in high-end laboratory equipment is actually fused silica. It is a material of paradoxes. It is glass, yet it withstands thermal shock that would shatter a Pyrex dish instantly.

You can heat a quartz tube to 1000°C and plunge it into ice water. It will survive.

This resilience comes from an incredibly low coefficient of thermal expansion. Because the material barely changes size when heated, it does not tear itself apart with internal stress.

However, this thermal invincibility has a ceiling. While the material’s theoretical softening point is around 1600°C, its structural integrity is compromised long before that temperature is reached.

The Invisible Enemy: Devitrification

The primary failure mode of a quartz tube is almost biological in nature. It ages.

Fused silica is amorphous. Its molecular structure is chaotic and random. This is what makes it "glass." Nature, however, prefers order.

When you hold quartz at temperatures above 1100°C for extended periods, the material attempts to return to a crystalline state. This process is called devitrification.

- The Symptom: The clear tube becomes cloudy or milky white.

- The Mechanism: The silica molecules realign into cristobalite crystals.

- The Result: The tube loses its thermal shock resistance. Upon cooling, the crystalline areas contract at different rates than the amorphous glass, leading to catastrophic cracking.

Devitrification is the silent killer of quartz tubes. It turns a flexible, resilient component into a brittle, fragile one.

The Vacuum Penalty

The environment inside the tube matters as much as the temperature.

In a vacuum furnace, the tube is fighting a war on two fronts. It is battling the thermal energy trying to melt it, and it is battling the atmospheric pressure trying to crush it.

At sea level, the atmosphere pushes against the outside of the tube with 14.7 psi of force. At room temperature, quartz ignores this. But as you approach 1100°C or 1200°C, the silica lattice softens slightly.

Under vacuum, the maximum safe temperature drops.

A tube that is perfectly stable at 1200°C in an air atmosphere may collapse or deform under its own weight at the same temperature under vacuum. The heat weakens the walls; the pressure finishes the job.

The Psychology of Limits

Operating a furnace is an exercise in risk management.

Think of the 1200°C rating like the redline on a car's tachometer. You can visit the redline, but you cannot live there.

If you run your furnace at its maximum rating continuously:

- Devitrification accelerates.

- Structural sag occurs.

- Lifespan plummets.

If your process requires holding 1200°C for hours at a time, quartz is likely the wrong material. You have moved past the "safe slope" and are dangling off the cliff. In these scenarios, the solution is not a better quartz tube, but a switch to Alumina (ceramic), which can handle temperatures up to 1700°C.

Summary: Variables That define the Limit

The following table outlines how different factors shift the "true" maximum temperature of your system.

| Factor | Effect on Max Temperature | The Engineering Reality |

|---|---|---|

| Atmosphere (Air) | Neutral | Can generally reach rated specs (approx. 1200°C). |

| Atmosphere (Vacuum) | Negative | Reduces structural strength. Max temp should be lowered to prevent collapse. |

| Purity | Positive | Higher purity fused silica resists devitrification longer. |

| Duration | Negative | Long hold times at peak temps accelerate crystallization (failure). |

Choosing the Right Tool

There is a distinct difference between what a machine can do and what it should do.

If your priority is equipment longevity, operate your quartz tube 100°C to 150°C below its stated maximum. If your priority is peak temperature performance, accept that the tube becomes a consumable item that requires frequent inspection for cloudiness.

At KINTEK, we understand that a furnace is only as good as the tube inside it. We specialize in navigating these material trade-offs. Whether you need high-purity quartz for sensitive semiconductor work or a robust alumina solution for extreme heat, we help you match the physics to the application.

Don't let a shattered tube stop your research. Let us help you calculate the real limits of your process.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube Laboratory Tubular Furnace

Related Articles

- Beyond the Spec Sheet: The Hidden Physics of a Tube Furnace's True Limit

- Installation of Tube Furnace Fitting Tee

- Your Tube Furnace Is Not the Problem—Your Choice of It Is

- Why Your High-Temperature Furnace Failed—And How to Prevent It From Happening Again

- Cracked Tubes, Contaminated Samples? Your Furnace Tube Is The Hidden Culprit