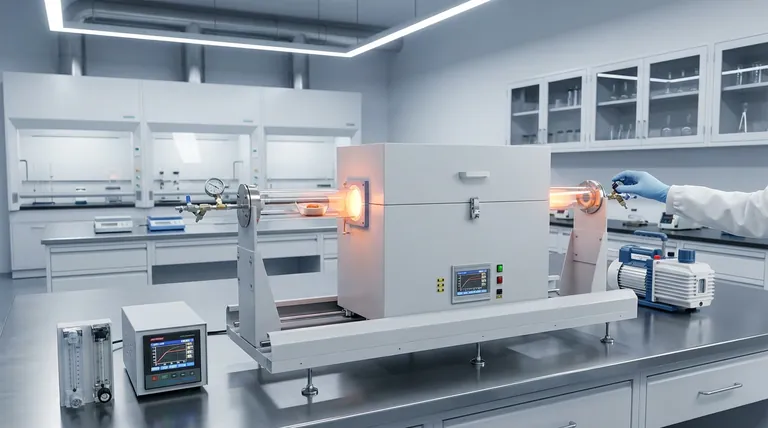

The Illusion of the Container

In laboratory science, we obsess over the variables we can control. We measure the sample weight to the microgram. We calibrate the temperature ramp to the second. We purify the gas flow to the part per million.

Yet, we often overlook the one variable that literally holds it all together: the furnace tube.

It is easy to view the tube as a passive vessel—a mere bucket for holding high-temperature events. This is a dangerous oversimplification. In thermal processing, the tube is not a bucket; it is a boundary condition. It is the only thing separating your pristine sample from the chaotic, dirty environment of the heating elements.

If the tube fails, the experiment doesn't just stop; it lies to you. It introduces impurities that mimic results, or it cracks, destroying weeks of preparation.

Understanding what your tube is made of—and why—is not a procurement detail. It is an engineering necessity.

The Engineering of Isolation

The furnace body is built for insulation and structure, typically crafted from stainless steel and ceramic fiber boards. But the process tube? The process tube is built for survival.

Its role is twofold:

- Containment: It holds the specific atmosphere (vacuum, argon, nitrogen) your chemistry requires.

- Exclusion: It blocks the contaminants shedding from the heating coils.

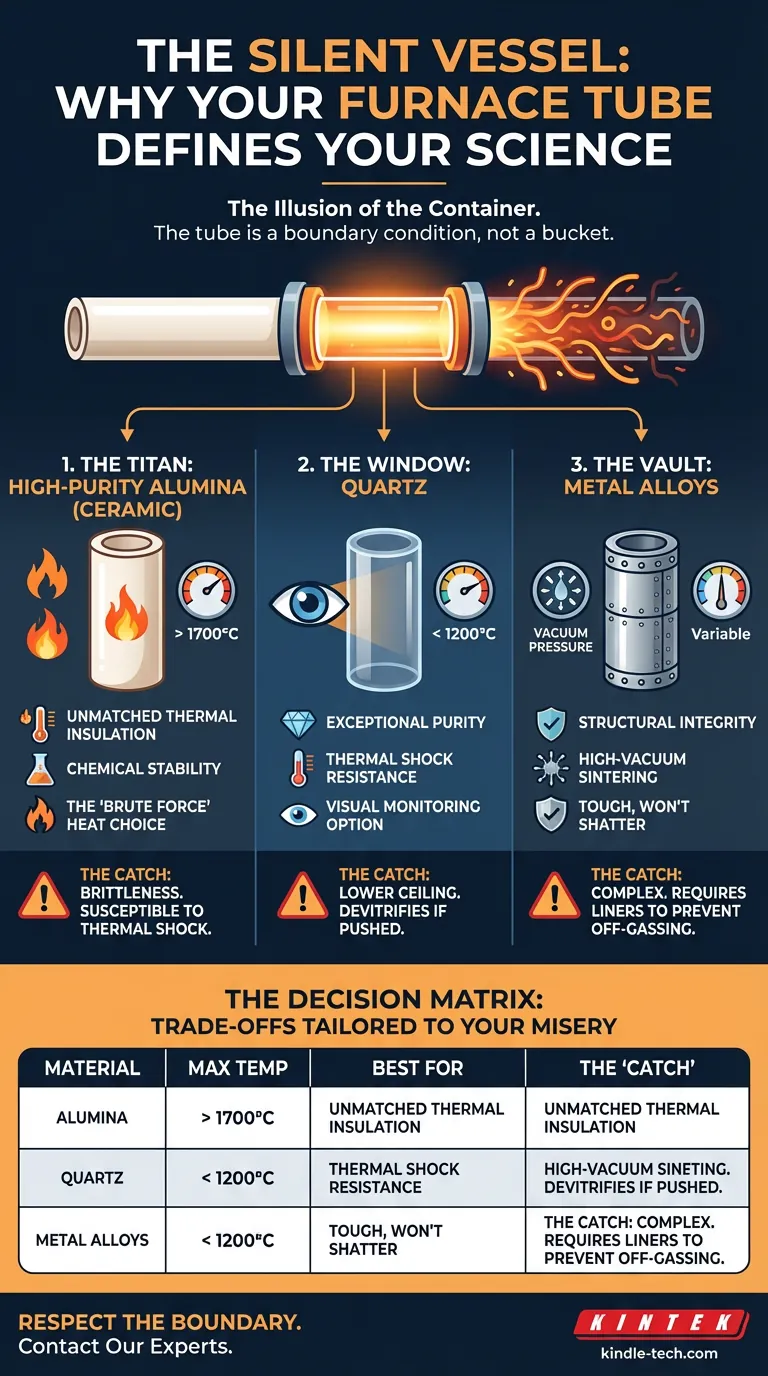

To achieve this, we rely on three primary materials. Each offers a distinct "personality" regarding thermal limits and chemical interaction.

1. The Titan: High-Purity Alumina (Ceramic)

When your experiment demands the extreme, you turn to Alumina ($Al_2O_3$).

It is the heavy lifter of the laboratory. High-purity alumina is a refractory ceramic designed to operate comfortably at temperatures where other materials liquefy or degrade—often well above 1700°C.

The Psychology of Alumina:

- The Strength: Unmatched thermal insulation and chemical stability. It is the choice for "brute force" heat.

- The Cost: Brittleness. Like many strong things, it does not bend; it breaks. It is highly susceptible to thermal shock. If you heat it or cool it too fast, it will crack. It demands patience.

2. The Window: Quartz

Quartz is the material of clarity.

Its primary advantage is transparency. In research scenarios where you need to visually monitor the sample as it reacts—watching for phase changes or melting points—quartz is the only viable option.

The Psychology of Quartz:

- The Strength: Exceptional purity and thermal shock resistance. Unlike alumina, it handles rapid temperature changes with grace.

- The Limit: It has a ceiling. Generally limited to 1200°C, quartz will begin to devitrify (turn cloudy and brittle) if pushed too hard or too long. It is perfect for the middle-ground, but it cannot touch the extremes.

3. The Vault: Metal Alloys

Sometimes, the challenge isn't just heat; it is pressure.

For processes like vacuum sintering, standard ceramics may be porous or difficult to seal. Specialized heat-resistant metal alloys are engineered for structural integrity under high vacuum.

The Psychology of Alloys:

- The Strength: They are tough. They don't shatter like glass or ceramic.

- The Nuance: At high temperatures, metals want to react. To prevent the tube from off-gassing and contaminating the sample, these tubes often require non-metallic inner liners. It is a complex solution for a complex problem.

The Economics of Trade-offs

There is no "perfect" tube material. There are only trade-offs tailored to your specific misery.

In engineering, as in life, optimizing for one variable usually stresses another.

- If you want visibility (Quartz), you sacrifice maximum temperature.

- If you want extreme heat (Alumina), you sacrifice mechanical toughness (thermal shock resistance).

- If you want vacuum integrity (Metal), you often sacrifice simplicity and cost.

The most common failure mode in selecting furnace tubes is not buying "bad" quality; it is buying the wrong tool for the environment. Using quartz for a 1500°C sintering run isn't ambitious; it's physics-defying. Using alumina for a process requiring rapid cooling is asking for a pile of shards.

The Decision Matrix

To simplify the selection process, match your constraint to the material properties below:

Conclusion: Respect the Boundary

The success of your thermal processing is defined by the weakest link in the chain. Often, that link is the tube.

Don't treat the tube material as an afterthought. It is a critical component dictated by your experiment's maximum temperature, chemical environment, and required atmosphere.

At KINTEK, we understand the engineering romance of high-temperature physics. We know that the difference between a breakthrough and a breakdown is often just a few degrees—and the right ceramic composition.

We specialize in matching the ideal tube material to your specific purity and thermal goals. whether you need the transparency of quartz or the resilience of alumina.

Are you pushing the limits of your current equipment? Contact Our Experts today to ensure your invisible boundary is strong enough to hold your science.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube Laboratory Tubular Furnace

- Laboratory High Pressure Vacuum Tube Furnace

Related Articles

- Exploring the Key Characteristics of Tube Heating Furnaces

- Advantages of Using CVD Tube Furnace for Coating

- The Geometry of Heat: Engineering the Perfect Thermal Environment

- The Geometry of Heat: Why Control Matters More Than Temperature

- Gravity, Geometry, and Heat: The Engineering Behind Tube Furnace Orientation