In engineering, a single number rarely tells the whole story.

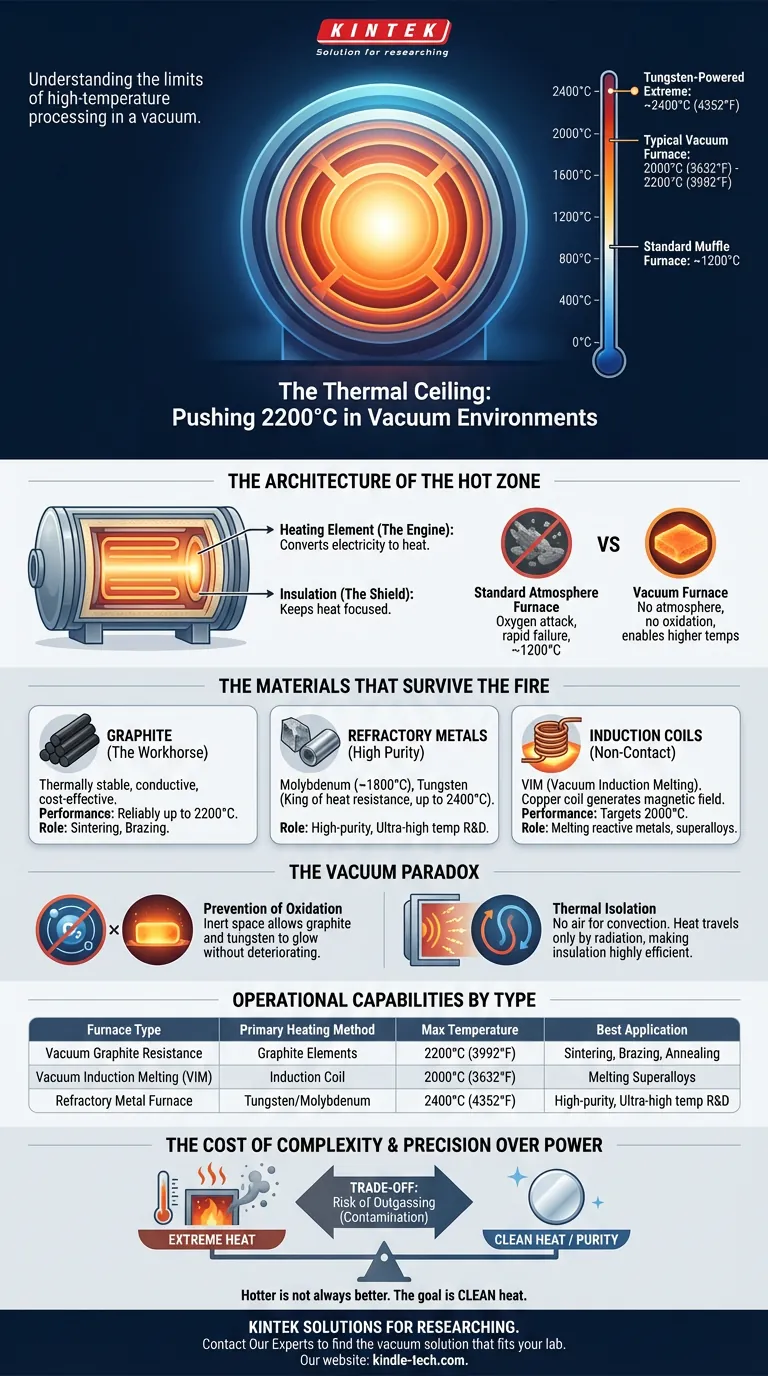

When asked how hot a vacuum furnace can get, the brochure answer is simple: between 2000°C (3632°F) and 2200°C (3992°F). In extreme cases utilizing tungsten, we can push toward 2400°C.

But for the engineer or material scientist, the maximum temperature is not just a limit on a dial. It is a physical negotiation between the energy you input and the structural integrity of the machine holding it.

To understand high-temperature processing, we must look inside the "black box" and appreciate the delicate systems that prevent these infernos from melting themselves.

The Architecture of the Hot Zone

The capability to reach 2200°C is not arbitrary. It is defined by the weakest link in the chain.

In a standard atmosphere furnace, oxygen is the enemy. At high temperatures, oxygen aggressively attacks heating elements, causing rapid oxidation and failure. This is why a standard muffle furnace usually caps out around 1200°C.

A vacuum furnace is different. By removing the atmosphere, we remove the chemistry of destruction. This allows us to use materials that would otherwise burn up in seconds.

The ultimate temperature relies on two internal components:

- The Heating Element: The engine that converts electricity to heat.

- The Insulation: The shield that keeps that heat focused.

The Materials That Survive the Fire

To generate extreme heat, we must use materials that refuse to melt. The engineering choices here are binary and distinct.

1. Graphite

Graphite is the workhorse of high-temperature processing. It is thermally stable, electrically conductive, and remarkably cost-effective.

- Performance: Reliably operates up to 2200°C.

- Role: Used in vacuum resistance furnaces for sintering and brazing.

2. Refractory Metals

When carbon contamination is a concern, or temperatures must go higher, we turn to metals with incredibly high melting points.

- Molybdenum: Effective up to ~1800°C.

- Tungsten: The king of heat resistance, pushing limits to 2400°C.

3. Induction Coils

In Vacuum Induction Melting (VIM), we don't use a resistor. We use a copper coil to generate a magnetic field.

- Performance: Typically targets 2000°C.

- Role: Melting reactive metals and superalloys without direct contact.

The Vacuum Paradox

There is a certain romance to the vacuum furnace. It protects by providing nothingness.

The vacuum serves two critical functions that allow for these extreme temperatures:

- Prevention of Oxidation: It creates a chemically inert space where graphite and tungsten can glow white-hot without deteriorating.

- Thermal Isolation: In a vacuum, there is no air to conduct heat via convection. Heat only travels by radiation. This makes the insulation packs—often rigid graphite felt—incredibly efficient.

Operational Capabilities by Type

Not all furnaces are built for the same "sprint." Different designs are optimized for different finish lines.

| Furnace Type | Primary Heating Method | Max Temperature | Best Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vacuum Graphite Resistance | Graphite Elements | 2200°C (3992°F) | Sintering, Brazing, Annealing |

| Vacuum Induction Melting (VIM) | Induction Coil | 2000°C (3632°F) | Melting Superalloys |

| Refractory Metal Furnace | Tungsten/Molybdenum | 2400°C (4352°F) | High-purity, Ultra-high temp R&D |

The Cost of Complexity

In complex systems, trade-offs are inevitable.

Pushing a furnace to its thermal limit introduces the risk of outgassing. As materials heat up, the internal components (insulation, fixtures) release trapped atoms.

At 2000°C, the furnace itself tries to become part of the atmosphere. If not managed correctly, this ruins the vacuum level and contaminates the sample. This is why "hotter" is not always "better."

The goal is not just heat; it is clean heat.

Choosing the right furnace requires balancing the raw temperature needed against the purity required by your specific application. It is the difference between using a sledgehammer and a scalpel.

Precision Over Power

At KINTEK, we understand that reliable data comes from reliable equipment. Whether you are sintering advanced ceramics or melting reactive alloys, the equipment must disappear into the background, leaving only consistent results.

Our engineers can help you navigate the trade-offs between graphite and metal zones, ensuring you have the exact thermal profile your research requires.

Contact Our Experts to discuss your specific temperature requirements and find the vacuum solution that fits your lab.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Graphite Vacuum Furnace Bottom Discharge Graphitization Furnace for Carbon Materials

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Pressure Sintering Furnace for High Temperature Applications

- Vertical High Temperature Graphite Vacuum Graphitization Furnace

- Graphite Vacuum Furnace High Thermal Conductivity Film Graphitization Furnace

Related Articles

- Why Your Heat-Treated Parts Fail: The Invisible Enemy in Your Furnace

- Beyond Heat: Mastering Material Purity in the Controlled Void of a Vacuum Furnace

- The Architecture of Emptiness: Achieving Metallurgical Perfection in a Vacuum

- The Engineering of Nothingness: Why Perfection Requires a Vacuum

- The Engineering of Nothingness: Why Vacuum Furnaces Define Material Integrity