High-tonnage pressure is the primary mechanism for inducing plastic deformation in solid-state battery materials, a process essential for converting loose powders into functional electrochemical cells. By applying force through a laboratory hydraulic press, you eliminate internal voids and force electrolyte and electrode particles to merge. This creates a dense, cohesive structure that minimizes contact resistance and establishes the continuous pathways necessary for efficient ion transport.

The Core Takeaway In solid-state batteries, the lack of liquid electrolytes means ions cannot flow across gaps; they require physical contact to move. The hydraulic press solves this by mechanically forcing solid particles to deform and bond, transforming high interfacial resistance into a highly conductive, unified solid interface.

The Mechanics of Densification

Plastic Deformation of Particles

The fundamental role of the hydraulic press is to overcome the natural rigidity of solid particles. When subjected to high pressure (often ranging from 400 MPa to 700 MPa), materials like sulfide electrolytes or LiBH4 undergo plastic deformation.

Instead of fracturing, these particles change shape. They flatten and spread against one another, effectively mimicking the "wetting" action of a liquid electrolyte but through purely mechanical means.

Elimination of Porosity

Loose powder mixtures contain significant void space, or pores. These pores act as insulators, blocking the flow of ions and electrons.

High uniaxial pressure collapses these voids, driving the relative density of the material up to approximately 99%. This creates a solid block where the active material, conductive carbon, and solid electrolyte are in intimate, uninterrupted contact.

Electrochemical Performance Improvements

Reducing Interfacial Resistance

The greatest barrier to solid-state battery performance is the high resistance at the solid-solid interface. If the layers merely touch, the contact area is microscopic, leading to high impedance.

By forcing the composite electrode powders to bond tightly with the electrolyte layer, the hydraulic press maximizes the active contact area. This drastic reduction in interfacial resistance is critical for enabling high-capacity performance, particularly in systems like lithium-sulfur or graphite/silicon anodes.

Enhancing Ion Transport and Conductivity

Ions require a "highway" to travel from the anode to the cathode. In a porous pellet, this highway is broken.

Densification reduces grain boundary resistance within the electrolyte itself. By crushing the particles together, the press shortens the distance ions must travel and ensures there are no physical gaps to jump, significantly improving overall ionic conductivity.

Structural Integrity and Fabrication

Creating a Dendrite Barrier

A dense electrolyte layer serves a dual purpose: conduction and protection. A laboratory hydraulic press can form thick pellets (e.g., >600 microns) that act as a physical shield.

By eliminating pores, the pressed electrolyte resists the penetration of lithium dendrites. In materials with a low Young's modulus, such as sulfides, this high-density barrier is vital for preventing short circuits during battery operation.

Activating Binders in Dry Electrodes

In dry electrode preparation, pressure does more than just compact; it activates the binder. When mixtures containing PTFE are pressed (e.g., at 400 MPa), the pressure promotes fibrillation.

This creates a microscopic, web-like network of binder fibers that anchors the active materials together. The result is a self-supporting electrode film with excellent mechanical strength, achieved without solvents.

Understanding the Trade-offs

While high pressure is beneficial, it requires careful calibration to avoid damaging the cell structure.

Material Fracture vs. Deformation

Not all materials deform plastically. While soft sulfides or polymers respond well to pressure, brittle oxide materials may fracture or crack if the pressure ramp is too aggressive or the total tonnage is too high. This can create new disconnects rather than solving them.

Thermal Considerations

Pressure alone may not suffice for polymer-based electrolytes (like PEO). In these cases, a "cold press" approach may result in poor interfacial contact. These materials often require a hydraulic hot press, where heat softens the polymer to conform to the electrode surface while pressure is applied, preventing damage that might occur from high pressure in a cold state.

Making the Right Choice for Your Goal

To maximize the utility of your laboratory hydraulic press, tailor your approach to the specific chemistry of your cell.

- If your primary focus is Sulfide Electrolytes: Utilize high cold pressure to exploit the material's low Young's modulus for maximum densification and dendrite blocking.

- If your primary focus is Polymer Electrolytes (e.g., PEO): Integrate heat with moderate pressure to soften the material, ensuring it conforms to the electrode surface without requiring excessive force.

- If your primary focus is Dry Electrode Film: Apply sufficient shear and pressure (around 400 MPa) to ensure PTFE fibrillation, which is necessary for creating a mechanically robust, free-standing film.

Ultimately, the hydraulic press is not just a compacting tool; it is an instrument for interface engineering, turning separate powders into a unified electrochemical system.

Summary Table:

| Mechanism | Impact on Battery Cell | Key Pressure Range |

|---|---|---|

| Plastic Deformation | Flattens particles to mimic "wetting" and bonding | 400 MPa - 700 MPa |

| Porosity Elimination | Collapses voids to achieve ~99% relative density | High Uniaxial Pressure |

| Interface Engineering | Maximizes contact area; reduces impedance | Material Dependent |

| Binder Activation | Promotes PTFE fibrillation for solvent-free films | ~400 MPa |

| Dendrite Barrier | Creates dense physical shield against short circuits | High Tonnage |

Elevate Your Battery Research with KINTEK Precision

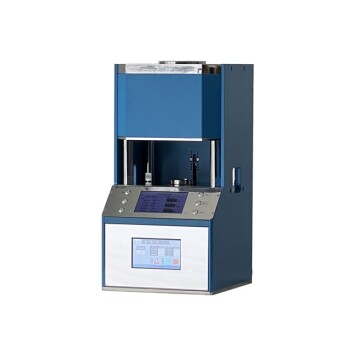

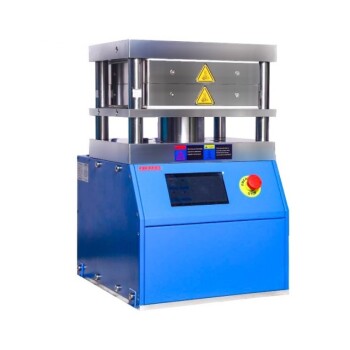

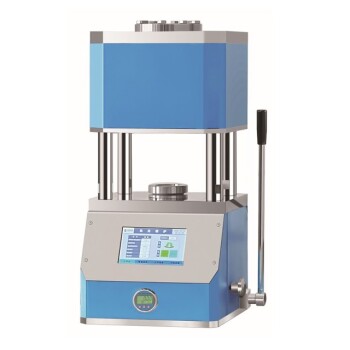

Achieving the perfect solid-solid interface requires more than just force—it requires precision. KINTEK specializes in advanced laboratory equipment designed to meet the rigorous demands of all-solid-state battery fabrication.

Whether you are working with soft sulfide electrolytes or brittle oxides, our comprehensive range of manual and automated hydraulic presses (pellet, hot, and isostatic) ensures you achieve the exact densification needed for high ionic conductivity.

Our value to your lab:

- Precision Engineering: High-pressure systems tailored for material densification and PTFE fibrillation.

- Versatile Solutions: From high-temperature furnaces for material synthesis to ultra-stable hydraulic presses for cell assembly.

- Expert Support: We provide the tools for crushing, milling, and sieving to ensure your precursor powders are perfectly prepared.

Ready to minimize contact resistance and maximize cell performance?

Contact KINTEK today to find the ideal pressing solution for your research.

Related Products

- Automatic High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Manual High Temperature Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Lab

- Laboratory Manual Hydraulic Pellet Press for Lab Use

- Automatic Heated Hydraulic Press Machine with Heated Plates for Laboratory Hot Press 25T 30T 50T

- Automatic Laboratory Hydraulic Pellet Press Machine for Lab Use

People Also Ask

- What is a heated hydraulic press used for? Essential Tool for Curing, Molding, and Laminating

- What is the role of a laboratory-grade heated hydraulic press in MEA fabrication? Optimize Fuel Cell Performance

- How much force can a hydraulic press exert? Understanding its immense power and design limits.

- How does a vacuum furnace environment influence sintered Ruthenium powder? Achieve High Purity and Theoretical Density

- Does a hydraulic press have heat? How Heated Platens Unlock Advanced Molding and Curing