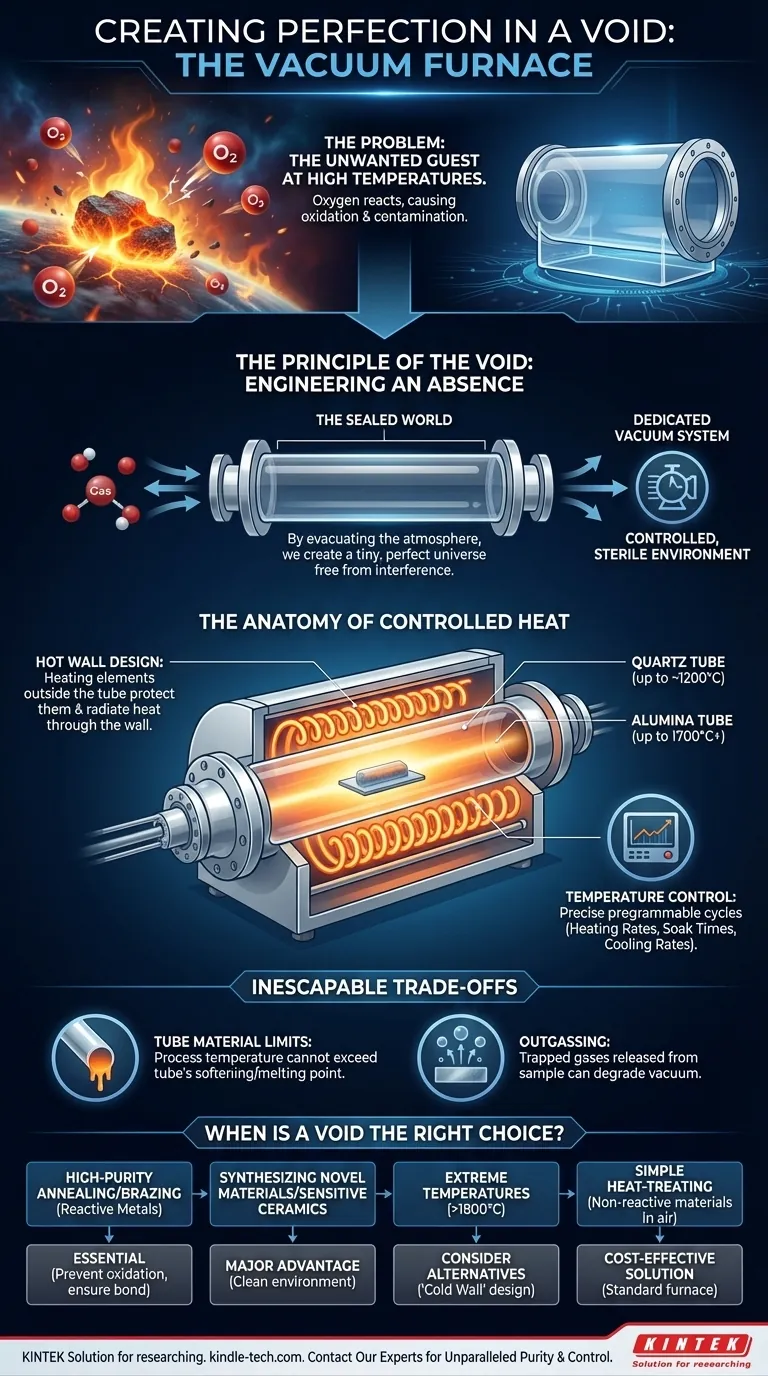

The Unwanted Guest at High Temperatures

Imagine a materials scientist on the verge of a breakthrough. A new alloy, a perfect crystal, a novel ceramic. The formula is correct, the process is planned. But as the material heats to hundreds or thousands of degrees, an invisible saboteur is always present: the air itself.

At high temperatures, the oxygen that sustains us becomes a destructive force. It eagerly reacts with sensitive materials, causing oxidation—a form of contamination that can ruin an entire experiment, compromise structural integrity, or alter a material's fundamental properties.

The core challenge isn't just about applying heat. It's about applying heat in a world of absolute purity, free from this unwanted guest. This is the problem the vacuum tube furnace was engineered to solve.

Engineering an Absence: The Principle of the Void

A vacuum furnace doesn't add anything to the process. Its power lies in what it removes. By evacuating the atmosphere from a sealed chamber, it creates a controlled, sterile environment where heat can do its work without interference.

This is an act of ultimate control. We are manipulating an invisible medium to prevent invisible reactions. It's a profound psychological shift from working with the environment to creating a new one from scratch—a tiny, perfect universe inside a tube.

The Sealed World

The foundation of this control is the furnace tube, sealed at both ends with vacuum flanges. This tube becomes the boundary between the chaotic, reactive atmosphere of the lab and the pristine, low-pressure environment within.

The entire assembly is housed in a robust steel shell, often with a water-cooling jacket. This shell doesn't just contain the heat; it resists the immense pressure of the outside atmosphere trying to rush back into the engineered void.

The Power of Pumping

A dedicated vacuum system is the engine that creates this absence. It physically removes gas molecules from the tube, lowering the internal pressure to a fraction of the surrounding atmosphere. This active removal of air is what prevents oxidation and other unwanted chemical reactions.

The Anatomy of Controlled Heat

While the concept is simple—remove the air, then add heat—the execution is an elegant dance of specialized components.

The Heart of the Process: The Furnace Tube

The tube is the stage where the transformation occurs. The choice of its material is critical, as it defines the limits of the possible.

- Quartz: A common and cost-effective choice, perfect for processes up to around 1200°C.

- Alumina: A high-purity ceramic that pushes the boundary, enabling temperatures of 1700°C or higher for more demanding applications.

The tube material isn't just a container; it's the primary constraint on your maximum operating temperature.

Heating from the Outside In: The "Hot Wall" Design

In a vacuum tube furnace, the heating elements are wrapped around the outside of the tube. This is a clever and crucial design feature known as a "hot wall" system.

Thermal energy radiates through the tube's wall to heat the sample inside. This elegant solution protects the delicate heating elements from the vacuum and any corrosive byproducts that might be released from the sample during the process.

The Conductor's Baton: Temperature Control

Heating is never a brute-force affair. A sophisticated controller acts as the furnace's brain, allowing for a precisely choreographed thermal cycle. Operators can program:

- Heating Rates: How quickly the temperature climbs.

- Soak Times: How long it holds at a peak temperature.

- Cooling Rates: How gradually or rapidly it cools.

This level of control ensures repeatability and allows for the precise tuning of a material's final properties.

The Inescapable Trade-Offs

Every powerful technology comes with constraints. Understanding them is key to making the right choice.

The Tyranny of the Tube Material

The "hot wall" design's primary limitation is that the process temperature can never exceed the softening or melting point of the furnace tube itself. The vessel that contains the heat is also the first thing to fail if pushed too far. This makes material selection paramount.

The Ghosts in the Machine: Outgassing

Even in a perfect vacuum, the material being heated can betray the environment. Trapped gases within the sample can be released as it heats up—a phenomenon called "outgassing." This can degrade the vacuum mid-process and must be managed by a capable pumping system.

When is a Void the Right Choice?

A vacuum furnace provides an unparalleled level of atmospheric control, but it's not always the necessary tool. Consider this your guide:

| Scenario | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| High-purity annealing or brazing of reactive metals | A vacuum furnace is essential to prevent oxidation and ensure a clean, strong bond. |

| Synthesizing novel materials or firing ceramics sensitive to contamination | The controlled, clean environment is a major advantage. |

| Processes requiring temperatures beyond 1800°C | You may need a different furnace type, like a "cold wall" design. |

| Simple heat-treating of robust, non-reactive materials in air | A standard atmosphere furnace is a far more cost-effective solution. |

Navigating these complexities to find the perfect thermal environment for your work is what we do best. For creating materials with unparalleled purity and control, KINTEK provides the essential vacuum furnaces and lab expertise to turn your scientific vision into reality. Contact Our Experts

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 2200 ℃ Graphite Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

Related Articles

- Maximizing Efficiency and Precision with Vacuum Graphite Furnaces

- How Vacuum Induction Melting Outperforms Traditional Methods in Advanced Alloy Production

- How Vacuum Induction Melting Ensures Unmatched Reliability in Critical Industries

- Optimizing Performance with Graphite Vacuum Furnaces: A Comprehensive Guide

- Heating in a Void: The Physics of Perfection in Material Science