The Art of Removing Everything

Perfection in material science is often defined by what isn’t there.

No oxygen. No moisture. No rogue particles.

A vacuum furnace is, at its fundamental level, a machine designed to manufacture "nothingness." It creates a hermetically sealed void so that thermal chemistry can happen without the interference of nature.

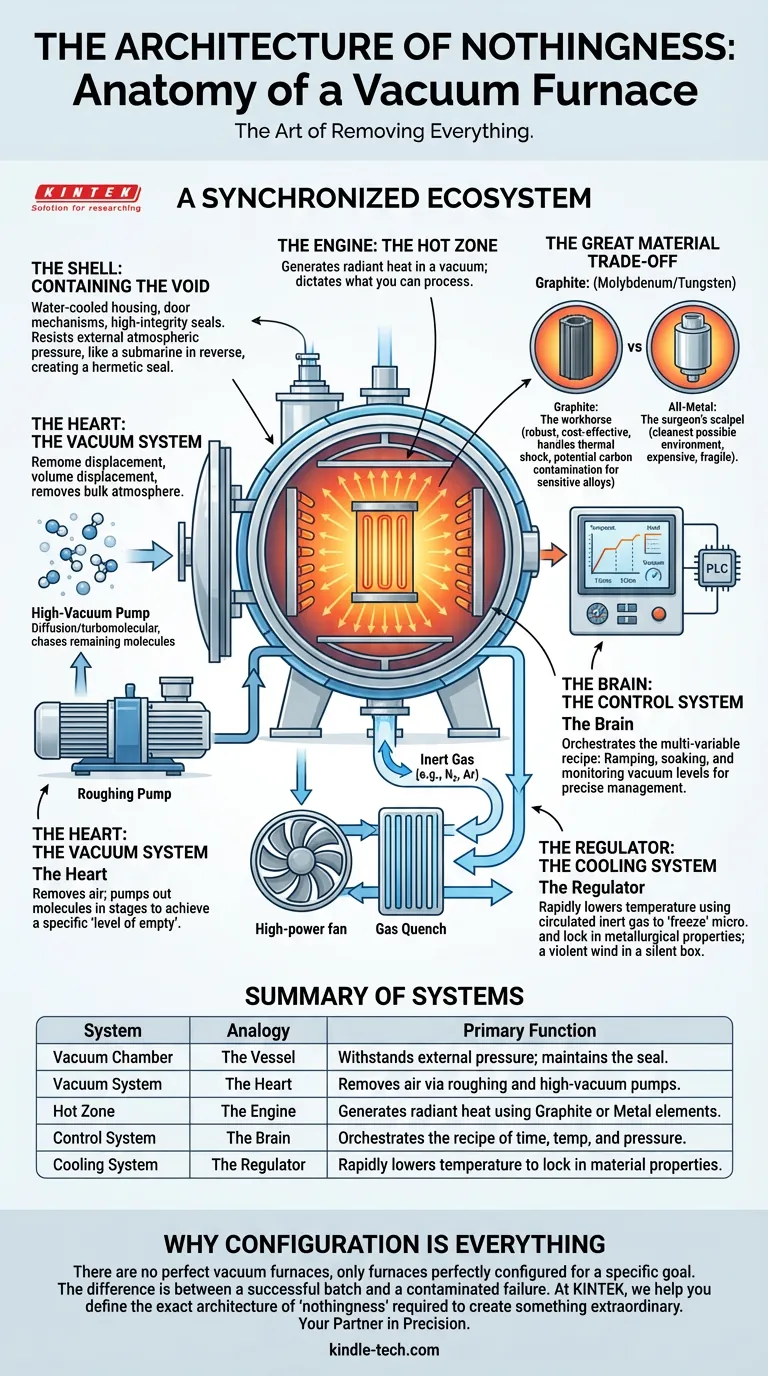

But calling it a "machine" oversimplifies the engineering reality. It is a synchronized ecosystem.

Like a human body, it relies on a heart (pumps), a brain (PLC), and a skin (chamber) working in concert. If one fails, the organism—and your expensive workload—fails.

Here is the anatomy of that ecosystem, and why the specific configuration of parts matters more than the sum of the whole.

The Shell: Containing the Void

The Vacuum Chamber is the vessel.

Its job seems passive, but it is actually fighting a constant battle against physics. When the internal vacuum is pulled, the atmospheric pressure on the outside of the vessel is immense. It is effectively a submarine in reverse.

It includes:

- The main housing (water-cooled to prevent warping).

- The door mechanisms.

- High-integrity seals.

The engineering romance here lies in the hermetic seal. It creates the boundary between the chaos of the outside world and the pristine order inside.

The Heart: The Vacuum System

The "heart" of the furnace doesn’t pump blood; it pumps out molecules.

This system is responsible for the heavy lifting of removing air. It is rarely a single component. It is a sequence of events designed to achieve a specific "level of empty."

- The Roughing Pump: This is the brute force. It removes the bulk of the atmosphere, taking the chamber from ambient pressure down to a rough vacuum.

- The High-Vacuum Pump: Once the air is thin, the precision work begins. Diffusion pumps or turbomolecular pumps take over to chase down the remaining molecules.

The Insight: You cannot achieve high vacuum with brute force alone. It requires a staged approach, transitioning from volume displacement to molecular capture.

The Engine: The Hot Zone

Once the void is established, the Heating System (or Hot Zone) comes alive.

Because there is no air to carry heat via convection (until the cooling phase), the furnace relies on radiation. Energy travels directly from the heating elements to your material.

This is where the "personality" of your furnace is determined. The materials used here dictate what you can and cannot process.

The Great Material Trade-off

The choice of hot zone material is the single most critical decision in furnace specification.

- Graphite: The workhorse. It is robust, cost-effective, and handles thermal shock well. However, in the microscopic world, graphite is carbon. For super-sensitive alloys, it can be a source of contamination.

- All-Metal (Molybdenum/Tungsten): The surgeon’s scalpel. It creates the cleanest possible environment. It is expensive and fragile, but for aerospace or medical implants, it is the only option.

The Brain: The Control System

Complexity requires management.

The Control System (typically a PLC) is the central nervous system. It does not just turn the heat on and off. It manages a multi-variable recipe:

- Ramping temperature at precise rates.

- "Soaking" (holding) temperature to allow thermal equilibrium.

- Monitoring vacuum levels to ensure no leaks occur during expansion.

In high-stakes material science, the operator is the pilot, but the Control System is the autopilot that prevents the plane from stalling.

The Regulator: The Cooling System

Heat treating is only half about heating. The other half is how you stop.

The Cooling System dictates the metallurgical properties of the metal. To harden steel, you must cool it rapidly to "freeze" the microstructure.

Modern furnaces use a Gas Quench. A high-power fan circulates inert gas (like nitrogen or argon) through the hot zone, stripping heat away from the parts and transferring it to a heat exchanger.

It is a violent wind in a silent box.

Summary of Systems

| System | Analogy | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Vacuum Chamber | The Vessel | Withstands external pressure; maintains the seal. |

| Vacuum System | The Heart | Removes air via roughing and high-vacuum pumps. |

| Hot Zone | The Engine | Generates radiant heat using Graphite or Metal elements. |

| Control System | The Brain | Orchestrates the recipe of time, temp, and pressure. |

| Cooling System | The Regulator | Rapidly lowers temperature to lock in material properties. |

Why Configuration is Everything

There are no perfect vacuum furnaces, only furnaces perfectly configured for a specific goal.

The engineer who wants to sinter robust automotive parts needs the durability of a graphite hot zone and the speed of an oil diffusion pump.

The scientist creating titanium medical implants needs the purity of an all-metal hot zone and the cleanliness of a dry pump.

The difference isn't just price; it's the difference between a successful batch and a contaminated failure.

Your Partner in Precision

At KINTEK, we understand that you aren't just buying a machine; you are investing in a process. Whether you need a robust solution for general heat treatment or a pristine environment for sensitive sintering, our lab equipment is designed to navigate these trade-offs.

We specialize in helping laboratories define the exact architecture of "nothingness" required to create something extraordinary.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- Vacuum Heat Treat Sintering Brazing Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace with Ceramic Fiber Liner

- Molybdenum Vacuum Heat Treat Furnace

- 2200 ℃ Tungsten Vacuum Heat Treat and Sintering Furnace

- Vacuum Heat Treat and Molybdenum Wire Sintering Furnace for Vacuum Sintering

Related Articles

- The Architecture of Emptiness: Achieving Metallurgical Perfection in a Vacuum

- Vacuum Induction Furnace Fault Inspection: Essential Procedures and Solutions

- Why Your Brazed Joints Fail: The Truth About Furnace Temperature and How to Master It

- Mastering Vacuum Furnace Brazing: Techniques, Applications, and Advantages

- Why Your High-Performance Parts Fail in the Furnace—And How to Fix It for Good