The Invisible Boundary

In any complex system, the most critical component is often the one you notice the least.

In surgery, it isn't always the scalpel; it is the sterile field. In thermal processing, it isn't always the heating element or the PID controller; it is the work tube.

The tube is the boundary condition. It is the physical negotiation between the violence of extreme heat and the delicate chemistry of your sample.

Engineers often view the tube furnace as a simple heater. But the material of that central tube—ceramic, glass, or alloy—is the single most deterministic factor in what your lab can achieve. It defines the limits of your temperature, the purity of your atmosphere, and ultimately, the integrity of your data.

The Psychology of Material Selection

When selecting equipment, we are often seduced by specifications we can control: ramp rates, dwell times, and software interfaces.

However, the choice of the tube material forces us to confront specifications we cannot negotiate with: Physics and Chemistry.

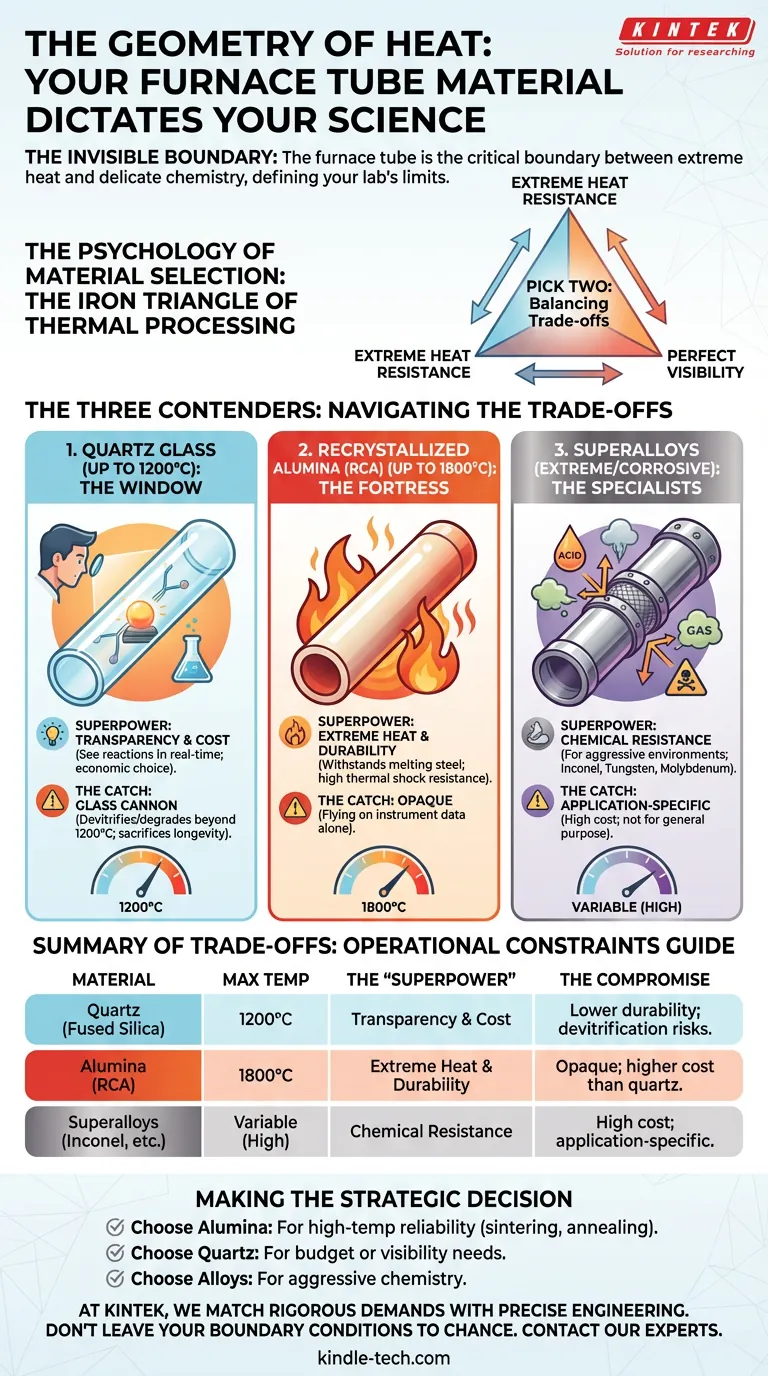

It is an exercise in managing trade-offs. You generally want three things:

- Extreme heat resistance.

- Perfect visibility.

- Low cost.

The reality of materials science dictates that you can rarely pick more than two. Understanding this "Iron Triangle" of thermal processing is the first step toward reliable results.

The Three Contenders

To navigate these trade-offs, we must look at the three primary classes of materials used in modern laboratories. Each represents a different philosophy of protection.

1. Quartz Glass: The Window (Up to 1200°C)

Fused quartz is the choice of the observer.

Its superpower is transparency. In processes where phase changes or reactions need to be visually monitored, quartz is irreplaceable. It allows you to see the science happening in real-time.

It is also the economic choice for "moderate" temperatures.

The Catch: Quartz is a glass cannon. While it handles thermal shock reasonably well compared to standard glass, it devitrifies (crystallizes) and degrades rapidly if pushed beyond 1200°C or subjected to too many distinct heat cycles. It sacrifices longevity for visibility.

2. Recrystallized Alumina (RCA): The Fortress (Up to 1800°C)

If quartz is a window, alumina is a bunker.

Ceramic tubes made from Recrystallized Alumina are the standard for high-performance thermal processing. They are built for endurance.

- Thermal Resilience: They withstand temperatures that would melt steel and soften glass.

- Cycle Life: They are highly resistant to thermal shock, surviving hundreds of heating and cooling cycles.

The Catch: They are opaque. Once the sample is inside, you are flying on instrument data alone. You are trading your eyes for the assurance that the tube will not fail at 1700°C.

3. Superalloys: The Specialists (Extreme/Corrosive)

Sometimes, the environment inside the tube is more dangerous than the heat itself.

For rocket engine research or the processing of aggressive chemicals, standard ceramics might react and contaminate the sample. Here, we turn to refractory metals and superalloys.

- Inconel: For specific high-temperature oxidation resistance.

- Tungsten/Molybdenum: For extreme chemical inertness against corrosive vapors.

These are not general-purpose tools; they are precision instruments for specific, hostile environments.

The Hidden Cost of Compatibility

The most expensive mistake in a lab is not buying the wrong furnace; it is ruining months of samples because of chemical incompatibility.

A tube is not a passive observer. At high temperatures, materials become reactive.

- Moisture and Volatiles: Samples containing organic binders or high moisture can outgas, creating corrosive atmospheres that eat through standard tubes.

- Chemical Attack: Certain vapors will attack the grain structure of alumina or etch quartz, leading to catastrophic failure or, worse, subtle contamination of your results.

Before you heat, you must verify that your vessel is inert relative to your chemistry.

Summary of Trade-offs

We have compiled the operational constraints of these materials into a simplified guide.

| Material | Max Temperature | The "Superpower" | The Compromise |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz (Fused Silica) | 1200°C | Transparency & Cost | Lower durability; devitrification risks. |

| Alumina (RCA) | 1800°C | Extreme Heat & Durability | Opaque; higher cost than quartz. |

| Superalloys (Inconel, etc.) | Variable (High) | Chemical Resistance | High cost; application-specific. |

Making the Strategic Decision

Your furnace is a long-term investment in your lab's capability. The tube you choose should not be an afterthought—it should be a reflection of your scientific goals.

- Choose Alumina if you need a workhorse for high-temperature sintering or annealing where reliability is paramount.

- Choose Quartz if you are on a budget or if the ability to witness the reaction is critical to your hypothesis.

- Choose Alloys if your chemistry is aggressive and demands a specialized shield.

At KINTEK, we understand that you aren't just buying a tube; you are buying the certainty that your equipment won't be the variable that ruins the experiment.

We specialize in matching the rigorous demands of your research with the precise engineering of our lab equipment. Don't leave your boundary conditions to chance.

Visual Guide

Related Products

- 1700℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- 1400℃ Laboratory High Temperature Tube Furnace with Alumina Tube

- Laboratory Rapid Thermal Processing (RTP) Quartz Tube Furnace

- 1200℃ Split Tube Furnace with Quartz Tube Laboratory Tubular Furnace

- High Temperature Alumina (Al2O3) Furnace Tube for Engineering Advanced Fine Ceramics

Related Articles

- Why Your Furnace Components Keep Failing—And the Material Science Fix

- Entropy and the Alumina Tube: The Art of Precision Maintenance

- Cracked Tubes, Contaminated Samples? Your Furnace Tube Is The Hidden Culprit

- Your Tube Furnace Is Not the Problem—Your Choice of It Is

- Why Your Ceramic Furnace Tubes Keep Cracking—And How to Choose the Right One